Bad news, kinksters: We officially do not have the constitutional right to engage in BDSM.

According to a new federal district court decision, the Constitution “does not prohibit the regulation of BDSM conduct.” In other words, the precedent implied by bans on anti-sodomy and anti-adultery laws—that adults have a constitutional right to freedom of noncommercial intimate conduct—doesn’t protect us. (I say “noncommercial” because, of course, professional sex workers have also never been protected.)

The decision came in response to a case of alleged sexual assault at George Mason University. A male student (“John Doe”) was expelled from GMU after a female non-student with whom he had a BDSM relationship accused him of continuing a sexual encounter, even after she tried to make him stop. (The question of whether she used the safe word they had negotiated in advance—“red”—is disputed.)

After he was expelled, Doe filed suit against GMU, saying that the university “disregarded” the context of BDSM and how it “affected matters like consent and related issues.” He based his “fundamental liberty interest argument on Lawrence v. Texas,” the Supreme Court case which struck down homophobic anti-sodomy laws in 2003. The court rejected the idea that Lawrence v. Texas might protect other sexual minorities (a category which, as I’ve argued before, should include fetishists and committed kinksters) because “there is no basis to conclude that tying up a willing submissive sex partner and subjecting him or her to whipping, choking, or other forms of domination is deeply rooted in … history.”

Excuse me? Most details of this complicated case are open to debate, but that last point is not. BDSM, without question, has a “deeply rooted” history—and that doesn’t change merely because the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia hasn’t done its reading.

I mean, good grief: Even just the words “sadism” and “masochism” have a rich history.

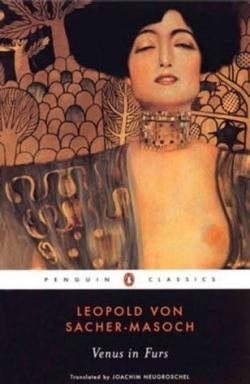

Penguin Classics

In 1869, an Austrian writer and journalist, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, signed a contract with his mistress making him her “slave” for a period of six months. (The contract stipulated that she wear furs as often as possible, especially when she was in a cruel mood, which later inspired Sacher-Masoch’s novella, Venus in Furs.) In 1886, when German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing wrote Psychopathia Sexualis, he coined the term “masochist” from Sacher-Masoch’s name.

The term “sadist” has an even longer history. In the eighteenth century, the Marquis de Sade inspired the term with his writings on violent sexual fantasies. (Napoleon Bonaparte found one of Sade’s stories,“Juliette,” to be so “abominable” and “depraved” that he ordered Sade’s arrest and imprisonment in an insane asylum.)

But if references to BDSM from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries aren’t sufficiently “rooted” in history for the court, perhaps the sixteenth century will suffice? One of my favorite literary descriptions of kink appeared in a 1599 collection of epigrams and elegies by John Davies and Christopher Marlowe. It reads:

When Francus comes to sollace with his whoore

He sends for rods and strips himselfe stark naked;

For his lust sleepes and will not rise before,

By whipping of the wench it be awaked.

I envie’him not, but wish I had the powre,

To make my selfe his wench but one halfe houre.

The court, I imagine, would reply that Francus’ desires are not constitutionally protected since “spanking or choking poses certain inherent risks to personal safety not present in more traditional types of sexual activity.” (I am still waiting for a court to explain to me why it formally recognizes spanking as a “risk to personal safety” in consensual adult behavior, but not a risk to personal safety when adults non-consensually do it to kids.)

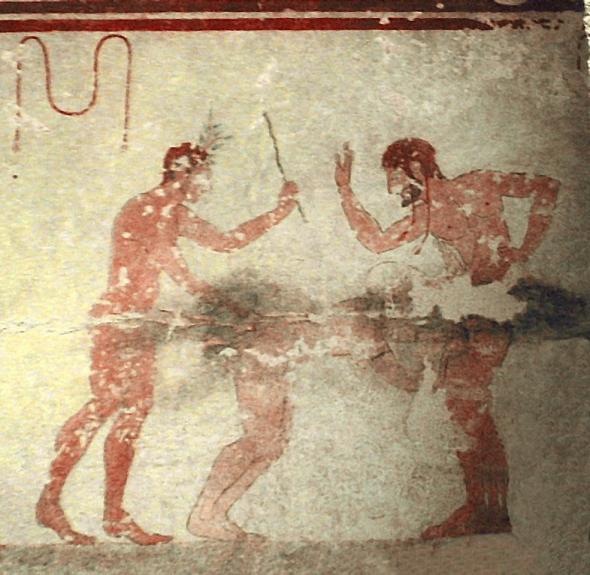

In any case, there are references to BDSM throughout historical literature: Robert Dixon, Thomas Middleton, John Fletcher, and William Shakespeare all referred to sadomasochism in their work. A fresco from approximately 490 BC in the aptly-named Etruscan “Tomb of the Whipping” even depicts two men flogging a woman in an erotic context!

But the court based its ruling on more than just an imagined absence of historical BDSM: It also argued that the gay community has “a judicially enforceable implied fundamental liberty interest in sexual intimacy because of the history of animus toward homosexuals.” In other words, because straights have long despised gay people, they have a special interest in legal protection for how they have sex. That is, without question, true.

But other sexual minorities, like kinksters, share that “fundamental liberty interest in sexual intimacy.” We share a “history of animus,” too.

In Johann Heinrich Meibom’s 1639 disquisition, On The Use of Flogging in Venereal Affairs (which was, according to academic David Savran, the authoritative text on the subject for two hundred years), the author “rejoice[s]” the fact that when such a “perverse” person was found in Germany, he or she would be “severely punished by avenging flames.”

In other words, he or she would be burned alive.

All consenting adults have the right to intimate lives that are free from government interference. It’s a shame that the court refused to recognize that—and a shame that the ruling attempts to draw lines around Lawrence v. Texas to divide “protect[ed]” sexual minorities from unprotected ones. Such divisions are, to steal the court’s language, not “deeply rooted” in history.

When sexual minorities burned, we burned together.