In 1970, gay activists in Chicago achieved a surprising victory. They successfully pressured the owners of the city’s biggest gay bars to drop their policy of throwing out any same-sex couple that danced together. And they couldn’t have done it without a little help from the Black Muslims—or at least their insurance agent.

Just boycott the gay bars for one night, the activists urged their fellow citizens. “Come to the Liberation Dance at the Coliseum and see what it’s like to do your thing in public,” read the flyers. It was a bold strategy, but there was a problem: The venue required an insurance policy, and every insurance agent the organizers approached said the risk was too great that the police would raid the dance, cart the attendees off to jail, and levy fines. Only on the day before the dance did the activists find a broker who’d sell them a policy—a black man whose company had insured the Nation of Islam’s annual convention at the same venue several weeks earlier.

In my work as an historian of gay American life, nothing I had read about gay liberation prepared me for this story. It made so little sense. After all, in those days the Nation of Islam, under the leadership of Elijah Muhammad, was known for propagating strictly defined roles for men and women—the very roles that gay liberationists were committed to defying.

But as I dug further, I realized the two groups were linked by more than an insurance agent. They also found themselves depending on the same local community of radical attorneys because they shared a common enemy: the police. The Liberation Dance took place just five months after the police assassination of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, leaders of the Black Panther Party of Illinois—an incident that unleashed a passionate response among Chicagoans of all races who recognized that police harassment and infiltration of radical groups simply had to be resisted. The gay liberationists’ young attorney, Renee Hanover, who had once been kicked out of law school in 1964 for being in a lesbian relationship, had defended members of the Blackstone Rangers and other militant black power activists against trumped-up criminal charges. And, of course, the Black Muslims knew a thing or two about how to deal with the police.

The story of how gay Chicagoans got their dance offers a vision of gay history—of distinct radical groups forging improbable, often messy alliances to achieve limited, but tangible, progress—that doesn’t fit the “first brick” heroic mythology we’re used to. But it’s far more in line with the often stunning reality of gay political organizing and empowerment in this country. If we want a comprehensive account of that history, these are the kinds of stories we need to know—so why do they remain so unfamiliar, even to a professional historian like me?

* * *

Too often, we tell gay American history from the standpoint of just two “vanguard” cities. “We are the gay Americans whose blood ran on the streets of San Francisco and New York,” President Barack Obama declared last year in Selma, Alabama, on the anniversary of the legendary voting rights march there, “just as blood ran down this bridge.”

In 1970, San Francisco and New York were home to 4 percent of the U.S. population and just over 10 percent of the gay bars listed in Damron’s Address Book, the most comprehensive national directory. Most gay people—and most gay activists—lived elsewhere.

Indeed, in every major U.S. city, the gay vote became a political force in the late 20th century. Where politicians had only quite recently sought easy political points from raiding gay bars, gays and lesbians acquired sufficient power and influence for elected officials to court them aggressively as a potential voting bloc—not least by campaigning in those same bars.

The path to gay political power and influence ran not only through the Castro district and Greenwich Village, but also—and even more importantly—through city hall in the nation’s dozens of other magnets for gay migration and community building: from Atlanta to Seattle, Boston to Dallas.

And as I argue in my recent book Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics, cities like Chicago are actually more representative of that early evolution. The Stonewall uprising and Harvey Milk’s election were important, but if they are the only stories in our history textbooks and popular culture, our grasp of the gay past is distorted.

How does gay history look different when we examine it in a city not strongly associated with homosexuality—that was a regional rather than a national gay mecca? Here are three key lessons I’ve distilled over the course of my work.

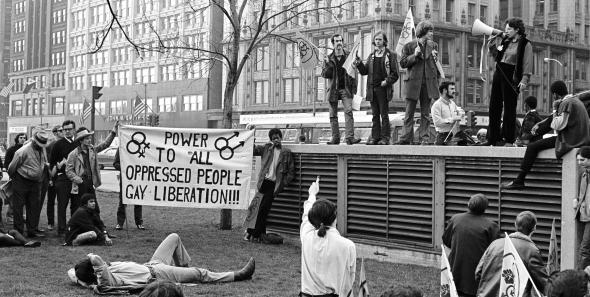

Photograph: Margaret Olin

Local gay political mobilization was not as indebted to national gay “watershed” moments as we tend to think.

There were turning points in Chicago’s gay political history, but they did not include the Stonewall rebellion or the election of Harvey Milk to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Instead, the key turning point in Chicago was the Democratic National Convention held there in August 1968.

By making it easier to challenge the police, the 1968 convention pushed Chicago’s gay movement toward more militant activism. In a year when assassinations and rioting rocked America’s cities and many felt the nation was becoming unglued, liberal Americans were troubled by spectacular police brutality directed at mostly white, peaceful demonstrators who came to Chicago to protest the Vietnam War. Just before the convention, Chicago cops raided Sam’s and the Annex, two of the city’s largest and busiest gay bars. At both locations, in a style familiar to local activists, plainclothes police infiltrated the bars long enough to be “propositioned” by patrons, then brought in uniformed colleagues to shut the place down and make arrests. Gay activists took an unprecedented step: They held a press conference denouncing the raids. In a petition labeled “Forgotten Citizens Unite,” they declared, “Every time there is an election or a political convention, the bars frequented by homosexuals are raided,” because officials “deem it a crime” for gay people to congregate.

Gay activists circulated their petition among the antiwar demonstrators in Lincoln and Grant parks—the first time gay Chicagoans had circulated a petition in public, asking strangers to sign in support of their cause. Taking advantage of the political opportunity offered by the local elites’ diminished confidence in the police, activists printed leaflets detailing “Your Rights If Arrested.” After the events of August 1968, Chicago gay activists challenged police harassment in the courts, in an increasingly sympathetic media, and in meetings with police officials.

Getting the cops out of gay bars was harder, took longer, and required more allies than in San Francisco and New York.

We take for granted that we got the police out of gay bars—indeed, most popular representations of Stonewall make it seem like that particular form of discrimination ended with the riots. But that wasn’t the case, especially not elsewhere in the country. For the gay movement, the right to be free from police harassment was the prerequisite for its later triumphs—but it took a lot of work.

In New York and San Francisco, bar owners filed lawsuits in defense of their right to operate a gay establishment earlier than their Chicago counterparts did. Partly as a result, police and liquor regulators in San Francisco and New York significantly reduced the frequency of routine police raids by the turn of the 1970s, though they still occurred from time to time. In Chicago, the first lawsuit successfully challenging police harassment was only filed in 1968—despite the fact that Illinois had repealed its sodomy law in 1961—but police raids persisted considerably longer.

The coalition that made possible the decline of gay bar raids in Chicago included both a left-liberal alliance focused on challenging police brutality, and also a series of police corruption trials in which a Republican prosecutor, hoping to damage the Daley machine’s Democratic stranglehold on local government, granted bartenders, including gay ones, immunity to testify that cops had shaken them down for cash bribes. Gay activists in San Francisco and New York moved on from focusing on policing in the 1960s to other issues in the 1970s—and historical narratives often assume that this shift happened everywhere else at the same time. For Chicago activists, police harassment continued to be the primary focus of their organizing for much of that decade. The turn away from policing, in fact, did not occur until after 1977, when Anita Bryant made gay rights a matter of national discussion for the first time.

In Chicago, routine police raids on gay bars dropped off somewhat after 1973 as the result of a police corruption scandal. But raids did continue to take place into the early 1980s. A major raid even occurred in 1985, although that time it led courts to award significant damages to the patrons present in the bar. “It might have been cheaper for state taxpayers if the agents had walked into Carol’s Speakeasy that night, handed $1,000 to each of the customers and sent them all home,” one columnist wrote.

The black political establishment had a bigger influence on the struggle for gay empowerment, although black-gay alliances broke down by the 1990s.

In Chicago, the need to curtail police harassment pushed gay activists to align their organizations with progressives, including black political leaders. This was possible partly because, in the two decades after the King assassination, a relatively strong strain of progressive black political leadership, including figures like Anna Langford, Danny K. Davis, and Jesse Jackson, checked the slowly growing influence of anti-gay black pastors aligned with the religious right. Working with and learning from the civil rights movement, beginning in the early 1960s, gay activists borrowed from the playbook of the black activists who increasingly challenged police brutality through protests and lawsuits. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, gay activists sought to expand the anti-discrimination apparatus of the state, even as President Ronald Reagan’s federal government was scaling back enforcement of such protections.

Not all black politicians supported gay rights. But it’s true that when the Chicago city council took up a gay rights ordinance for the first time in 1986, black aldermen held the balance of power. In two votes on gay rights in 1988, as in the 1986 vote, Chicago’s black aldermen voted yes in larger proportions than their white counterparts. A key reason for this is that a majority of white aldermen were fearful of bucking the very vocal opposition from the Roman Catholic archbishop.

Photograph: Margaret Olin

Nonetheless, the social basis of black-gay alliances were already beginning to break down in the 1970s because the new gay community institutions and organizations created in that decade were almost uniformly located on the city’s predominantly white North Side. One black Chicagoan in the late 1970s bristled at the racism he encountered from white gay men. “You wouldn’t believe how many gays there are in good jobs, on the management level,” he said. “And especially when it comes to blacks, most likely the gay will be doing the firing, rather than getting fired.”

Gay identity itself—and especially the forms that visible, “out” gay self-identification took—was being redefined through what the late historian Allan Bérubé called “whitening practices.” In Chicago as much as anywhere, the geographic centering of gay politics on the white side of town hardened this perceptual link between gayness and whiteness. A city-sponsored, $3.2 million gay-themed streetscape renovation project was completed in 1998 in the North Side’s East Lakeview district, where its commercial strip was by then known as “Boystown,” promoting tourism and enriching city lawyers and contractors. The uneven economic development of North Side and South Side neighborhoods brought about tensions over policing and programming, and the AIDS crisis worsened those tensions by overlaying them with conflicts about respectability and resources.

Even as urban white gays shook off the burden of routine police harassment and worked with police officials to institute sensitivity training and to recruit gay officers, racial tensions developed. Activists began at times to respond to anti-gay violence with calls for intensified policing, a move that black, Latino, and other activists of color have resisted. Gay male politics, in particular, proved surprisingly compatible with urban machine politics. Indeed, down to the parades, the rainbow flags, the tavern keepers as power brokers, and the preoccupation with electing their own, the contours of gay politics by the 1990s bore more than a passing resemblance to white ethnic politics of the early and middle 20th century.

* * *

Reframing gay history beyond the vanguard cities reveals both the radical roots of the gay movement and its subsequent turn toward the political mainstream. Only 50 years ago, gays and lesbians were social and political pariahs, facing harassment wherever they gathered. And even as they won power at city hall, at the state and federal levels gays and lesbians remained weak, unable even in the 1990s to prevent passage of “defense-of-marriage” laws and a newly codified ban on gays in the military.

Today, of course, gay activists have powerful friends not only in city hall but in the White House. The nation’s first president from Chicago has done more than any previous American leader to enact equality for gay and lesbian Americans, ushering in a wave of progress at every level of government. The increasing role of gays and lesbians in the Democratic Party coalition was reflected in Obama’s high-profile announcement in mid-2012, as his re-election campaign was getting underway, of his support for marriage equality for same-sex couples. It was a dramatic departure from the pattern of Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, each of whom swerved sharply to the right on gay rights—in fact, on gay marriage in particular—during their own re-election campaigns. The largest donor to Obama’s 2012 “super PAC,” Priorities Action USA, was the openly gay Chicago media executive Fred Eychaner. In his second term, Obama nominated four openly gay major campaign donors, all white men, to ambassadorships.

Indeed, by 2013, the chief justice of the United States suggested that the gay-rights “lobby” was so “politically powerful” that gay couples denied equal access to marriage should not be considered a disadvantaged class deserving the protection from the courts. The question today is not so much whether gay people can influence the political process, but what we will do with our newfound clout.