Even if you don’t recognize the full name, there’s a good chance you already know a few true things about Holly Woodlawn: that she came from Miami, F.L.A.; that she hitchhiked her way across the U.S.A.; that she plucked her eyebrows on the way, shaved her legs, and then he was a she. Unfortunately, there isn’t anyone left to verify whether or not she actually said, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side.”

Holly Woodlawn passed away Sunday, Dec. 6, at the age of 69. She once said of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” that she never made a cent off the song, but it did earn her immortality. That exchange, in fact, describes much of her professional career. But then again, what exactly was her professional career? She acted, she modeled, she just hung around. She tried to impersonate the wife of the French ambassador to the United Nations (for which she got arrested). It’s difficult to explain to those who’ve never heard of Holly Woodlawn what she “did,” largely because whenever people ask that question, they tend to confuse achievement with financial earnings. Holly did a lot of everything and made not much money from anything. So what did Holly do? She lived on chutzpah; she was a star, truly; she was iconic, truly; she was simply herself, and that was everything.

She ran away to New York in the early 1960s, and survived as a teenage hustler. She spent a lot of time at the famed club Max’s Kansas City; she took a lot of drugs, went to a lot of parties, and met people. Eventually, via Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, she fell in with Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling, two other transgender kids who were also just hanging around, and the three of them christened themselves Warhol’s Superstars—entirely without Warhol’s knowledge or permission, but much to Warhol’s amusement.

The trio were largely regarded as a joke, in and among the Factory crowd: These three people who fell in and out of gender (both Jackie and Holly were on and off hormones their entire lives) fancied themselves Superstars without ever having really “done” anything. For Warhol, passing these three “freaks” off as his own starlets was a fun subversion of the Old Hollywood star system. But in that gesture lies their collective crucial achievement: self-invention. They were all down-and-out, flotsam in a world that had no regard for any of them. No one was ever going to tell them they were stars. They didn’t need Warhol’s blessing, or anyone else’s, for that matter. They simply had to bless themselves. And so they did.

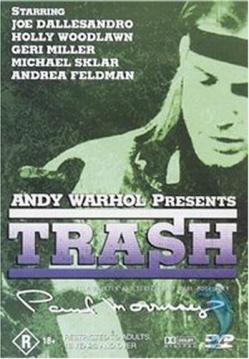

I first encountered Holly the same way everyone else did—in Paul Morrissey’s Trash (1970), a picaresque tale of a junkie (the ineffably gorgeous Joe D’Allesandro) meandering from place to place trying to find a fix. He lives with Holly (Woodlawn) in a derelict basement apartment that she furnishes with the trash she finds on the curb. The thematic engine of the film is a product of Morrissey’s reactionary conservatism: All these hippies and junkies and freaks are social trash, and so they live among trash. Holly’s casting in and of itself is meant as a kind of vicious joke—here was this gangly, weird creature who thinks she’s a woman next to the passive Apollonian beauty of Joe.

IMDB.

The simplistic morality of Morrissey’s film is outshone by the astonishing personalities that populate it—the braying Andrea “Whips” Feldman, the playfully sadistic Jane Forth—and no one in this film shines brighter than Holly herself. And in this single transcendent performance, Holly blazed a trail for a revolutionary mode of queerness.

In a movie replete with excessive personalities, Holly is deeply human. This is not to say that she herself isn’t excessive; on the contrary, she radiates a glorious comedic too-much-ness. Her movements are jangly and tourettic, her dialogue is punctuated by a rolodex of seemingly involuntary elastic facial expressions. But unlike her fellow cast members, her outlandishness springs from a font of vulnerability. There is no preening, no protective screen of artifice, Holly just is. After a failed attempt at seducing the strung-out, impotent Joe, she begins to masturbate with an empty beer bottle. In and among her hysterical orgasmic convulsions, she reaches out to Joe and holds his hand, and the camera lingers on this momentary tenderness in and among the trash. “Is it OK, Holly?” asks Joe, nodding off. “Yeah, Joe, it’s fabulous,” she responds with the breathless gravity of Elizabeth Taylor.

Holly stands alone in Trash in that she is the only one in the film to not only refuse, but also to transmute Morrissey’s sneeringly dismissive intent. She is berated throughout the film by all the characters for her dumpster-diving ways, and her retort is always the same: “It’s not trash!” Sometimes she sells her finds, but mostly, she lives among them. She exists on the margins of the margin, and so her life is a product not just of her own invention, but of her own transformative investment. A discarded sink becomes a couch; a lone drawer becomes a bassinet; her shoes are irreplaceable and not to be bartered, because she “found them in the garbage.” These are her things, and their value has nothing to do with monetary currency—only the currency of Holly’s own queer possession. In her irrepressible humanity, in her hilarity and vulnerability and excessiveness, in her claiming her own space, her own name, and her own title, Holly embodies the difference between worth and value. Her things are not trash, because she herself has claimed them, and they are therefore priceless. She is not trash; she is, indeed, a Superstar.

What did Holly Woodlawn do? She showed us how to live as queer people. Never rely on other people to name you. Be excessive, loud, funny, and vulnerable. Find a way, like Holly, to live your life among the rubble and still be surrounded by treasure.