Cruising—the gay male pastime of looking for sex with strangers, sometimes in semi-public places—usually keeps a low profile. But it’s having a moment in the art world: At the end of October, two photography books focused on cruising spots in New York City hit the shelves, inviting readers to become voyeurs. Alvin Baltrop’s The Piers documents the fabled heyday of cruising on Manhattan’s Hudson River piers in the 1970s and ’80s. Moving to the present, Thomas Roma’s In the Vale of Cashmere explores a faded cruising spot frequented primarily by men of color in Prospect Park. At a moment when gay bars, hook-up apps, and the bright light of straight tolerance are said to have eliminated the need for furtive trysts in hidden public spaces, these new monographs raise a question: Why do some gay men still search for each other in the shadows?

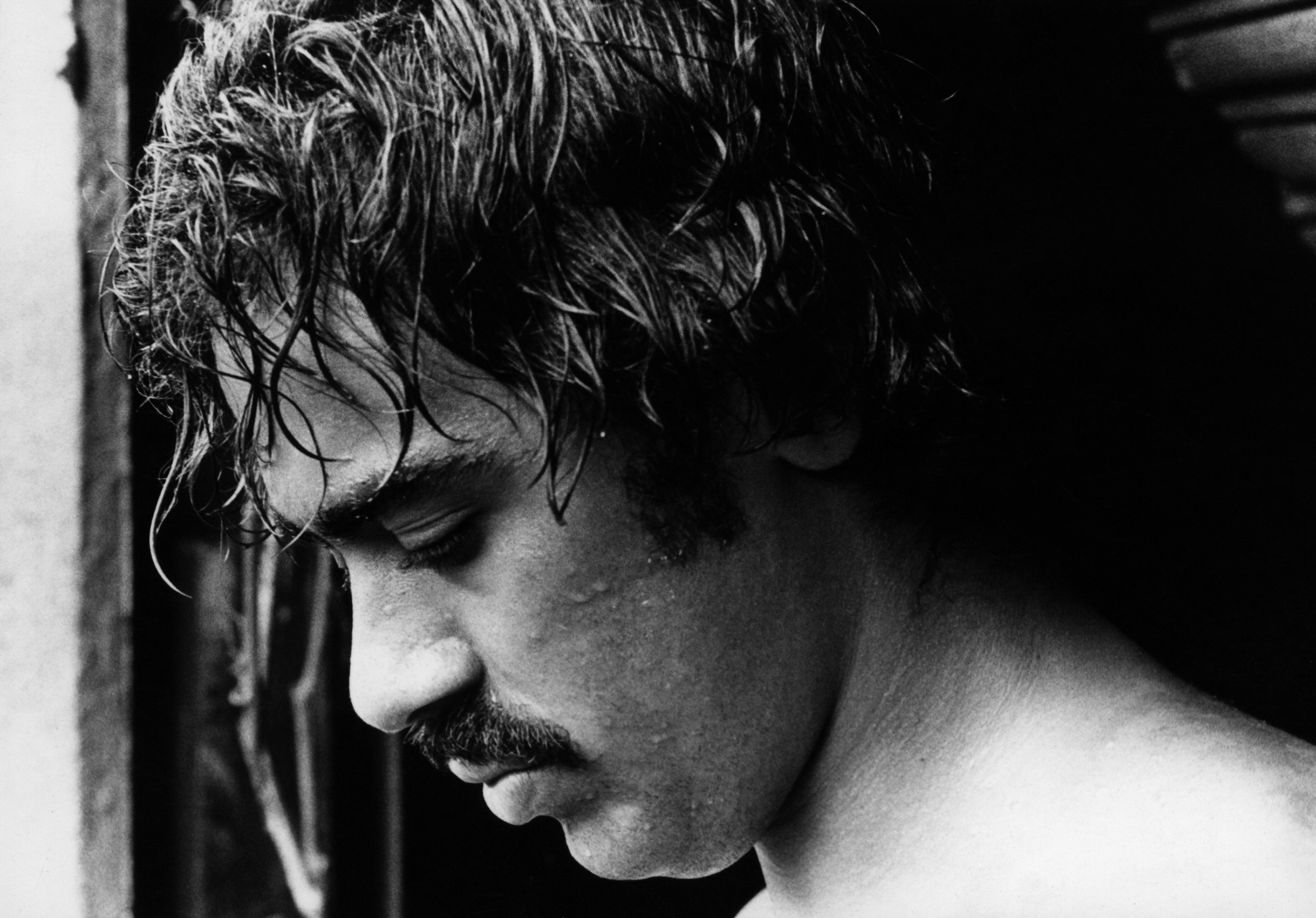

In The Piers, Alvin Baltrop captures New York’s semi-abandoned West Side waterfront in the decades just after Stonewall, where empty warehouses offered an alluring—albeit often dangerous—escape for men seeking sex with men. As Glenn O’Brien writes in his introduction, Baltrop’s blunt photographs capture the thrills and perils of a time when much of gay life was still “by necessity secret.” Many of the men portrayed in the series have come to the piers because they are “leading double lives.” Afraid to get caught bringing a man home, and unwilling to patronize gay bars, they turn to the rotting and crime-ravaged piers in part as a necessary evil—it’s either sex there, or sex nowhere.

Alvin Baltrop. Courtesy of Alvin Baltrop Trust, Third Streaming, and TF Editores.

But Baltrop doesn’t focus solely on the piers’ dark, desperate side. He also points to their strange beauty, depicting them as a sort of post-apocalyptic gay paradise. Sure, he documents a brutal murder scene—such violence was not uncommon. But he also illustrates how the piers served as a “poor man’s Fire Island,” referencing the famed gay Long Island enclave, “a place to sunbathe, socialize and cruise.” He offers portraits of beefy men, many of them likely quite out of the closet, chatting happily, sprawled out naked on beach towels, or gathering casually for group play.

Alvin Baltrop. Courtesy of Alvin Baltrop Trust, Third Streaming, and TF Editores.

Baltrop’s piers seem to offer something beyond a permissive space for gay sex. Looking at his intertwined subjects, I recall writer Hilton Als’ remarks regarding his own encounter with the piers. As a young man, Als recalls in “Notes on My Mother,” they helped him lay claim to a sense of romance that he had previously associated only with his mother, who left her home in Barbados in part to pursue a love affair: “I avoided explaining [to my mother] the impetus that propelled me to leave her home in Brooklyn for the piers on the West Side Highway. I avoided explaining that I had been motivated by the same desire and romantic greed that had propelled her to move from Barbados to New York. I avoided explaining that when I sat in parked cars with one man and then another, I felt closer to her experience of the world than I ever did in her actual presence.” In the hidden world of the piers, men like Als could find a sense of romantic adventure, immediacy—the thrill of exploring the unknown.

Alvin Baltrop. Courtesy of Alvin Baltrop Trust, Third Streaming, and TF Editores.

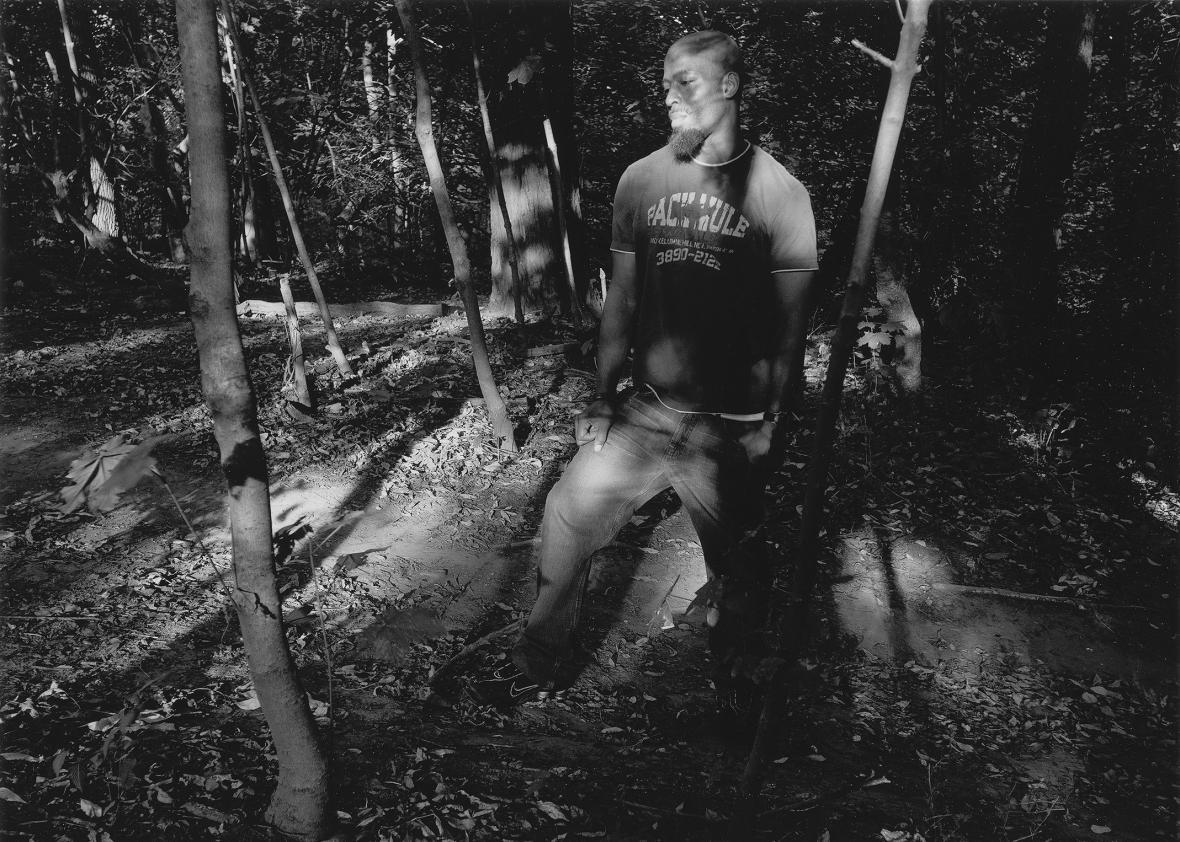

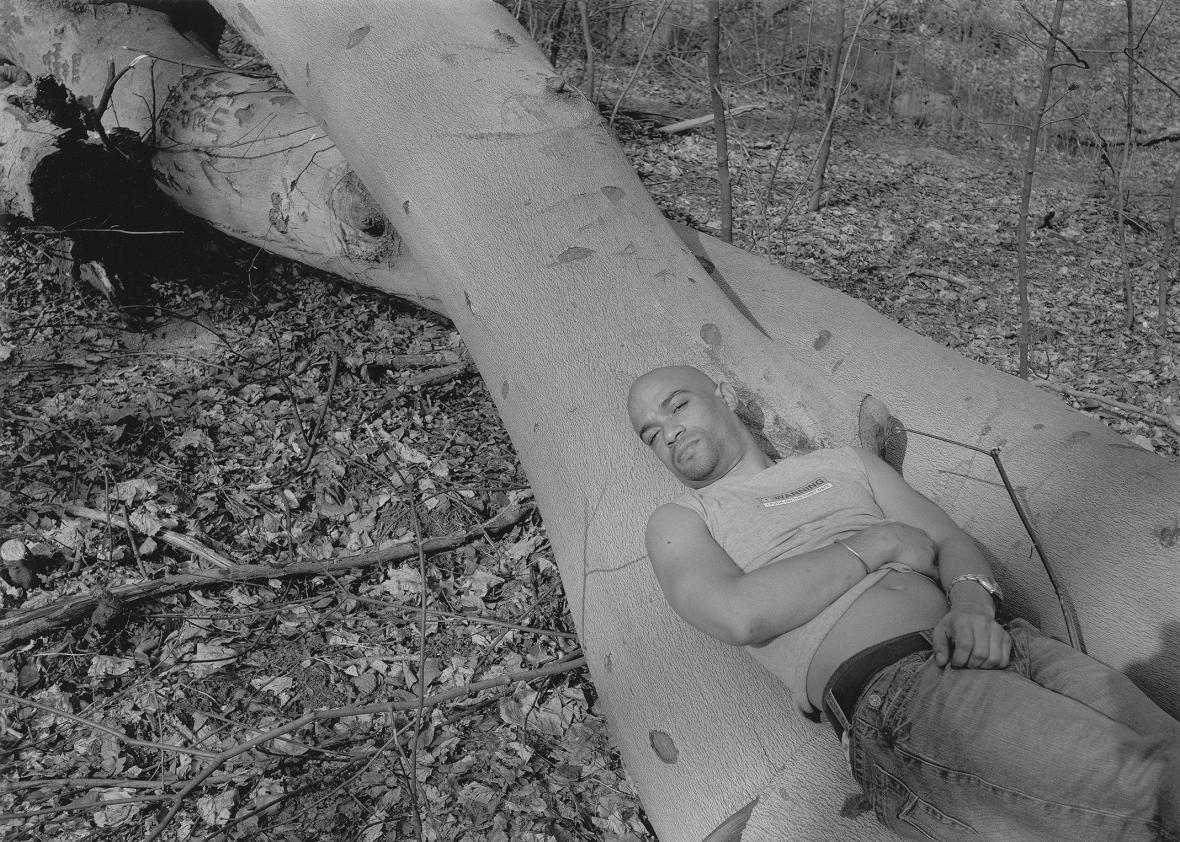

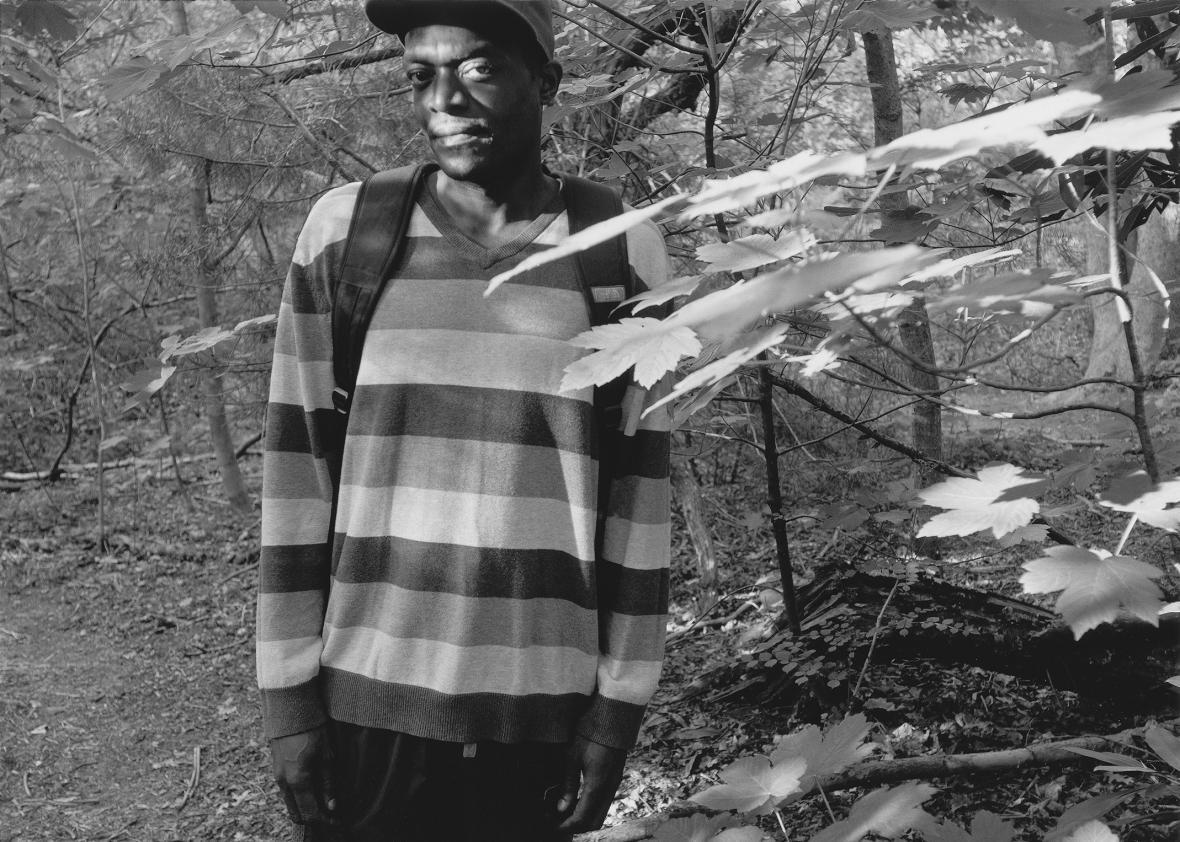

Perhaps the romantic allure of the unknown is what has allowed cruising spots to survive, at least to some extent, the sea changes that gay culture has undergone since the ’70s. That’s what Thomas Roma seems to suggest in his book In the Vale of Cashmere. Cashmere comprises straightforward portraits of the men who still visit a cruising spot in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, introducing them alongside elliptical shots of the landscape they wander. Unlike Baltrop, Roma doesn’t capture sexual play, but he still manages to capture the desires of his portrait subjects. In their steady gazes, he finds their restlessness, their sensuality, their hunger for exploration.

Thomas Roma. Courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.

After seeing some of the images from Cashmere, a friend of mine sent a link to a cruising website, a sort of Yelp.com for gay cruising spots around the world. In the comments thread about Prospect Park, one reviewer complained that it had become dull. The age of Craigslist had made the place obsolete, he explained; he gave the spot a low rating. And yet here, within Cashmere’s pages, we find evidence that the embers of Prospect Park’s cruising scene still burn—that though the park may be quieter, it remains magnetic for solitary men in search of adventure. As G. Winston James writes in his introduction, Roma’s contemporary images evoke the “the uncontrollable trembling I sometimes felt as I entered the park awash in a mixture of anticipation and angst. The thudding of my heart that I experienced at moments, knowing that I was by myself under the night sky, but not at all alone.” Roma’s images hint that these thrills are still available for those willing to look.

Thomas Roma. Courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.

In marking two points on the trajectory of New York’s cruising culture—the apogee that preceded the AIDS crisis, and the current low plateau—Piers and Cashmere open a conversation about an aspect of gay culture that gays have trouble discussing openly, even among ourselves. Listen in on a conversation about cruising spots, and you’ll hear the speakers split up into two teams. Half of the boys say they’ve never been cruising because it’s dangerous, disgusting, and passé. The other half say they’ve been to so many cruising spots all over the world that they hit the parks as casually as they bar-hop. But once everyone has declared whether they think cruising is yucky or sexy, no one asks: What is cruising really about? What needs, beyond orgasm, does it satisfy? And why do openly gay men do it when there are so many other options?

After all, there are many reasons to stop having sex on the sly in public places. First, all that sneakiness suggests that there’s something wrong with gay sex, that it should be hidden. And then there’s something uncomfortable about out and proud men who make a fetishistic game of risky, secretive sex, while so many others engage in it only because they are closeted, afraid for their reputation or their lives. In his text Screwball Asses, Guy Hocquenghem puts it beautifully: “I know how many queers only have toilets in which to touch each other. It depresses me that those who have decided to come out of hiding continue to project their excitement in the miserable places that the system condescends to allow them.” It seems odd to choose illicit public sex when you have other options. And it feels somehow exploitive to be out and free, but take little tours to fuck the closeted in the only spaces where they can express themselves sexually.

Thomas Roma. Courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.

There’s a more straightforward reason to abandon cruising spots, too: In my experience, they’re miserable places.

Every, summer, I find myself inexorably drawn to Upper Manhattan’s parks at night. Sometimes I’m just tagging along with a friend or a partner—but for the most part, I go alone, without letting anyone know where I’ve gone. When I leave the street and descend into a park, I feel my heart pound in anticipation, just as James describes in Cashmere. Like Als, I feel that I am laying claim to my own darkly romantic story. But then the electricity begins to dissipate. I pace the same paths for hours, slowly lowering my expectations in order to hook up with whatever’s available. I realize I’m bored. And the men, even when they are beautiful and plentiful, seem just as ambivalent about the situation as I do. Despite the heady stories one hears about the ’70s and ’80s, a night of cruising these days always ends feeling hollow, even pathetic. For most of us modern cruisers, sex has become banal—it has lost its capacity to surprise and delight. And so we move not like revelers, but like lost souls in some forgotten ring of Dante’s Inferno, condemned to go through the motions of desire without feeling its pleasures.

And yet we still hit the parks. In a country where gay sex is legal, some of us still insist on grasping for it while hidden among the trees after dark. In a time when gay men gather publicly in droves, we gather secretly in furtive little groups. When I try to explain my participation in the phenomenon to friends or even myself, I blame the unremitting heartbreak following a four-year relationship; or the anxiety around intimacy that cripples both my sister and me; or an inexplicable desire for self-destruction.

But maybe that’s overly dramatic. Two summers ago, I ran into a gorgeous cruiser on my way to the park. He was singing a mournful gospel tune under his breath. Someone like him could have had any boy he wanted at a Chelsea bar, but there he was, trudging doggedly toward a well-known spot. Baffled, I asked what someone like him was doing here. He shrugged. “I have to work early tomorrow. This is easy.”

Thomas Roma. Courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.

“Thomas Roma: In the Vale of Cashmere” is on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York City, through Dec. 19, 2015.