An ad that aired frequently in Houston this past month depicted a man accosting a young girl in a bathroom stall. Its purpose was to convince voters about the dangers of the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance, known as HERO, which protected 15 classes of people from discrimination, including LGBT people. Opponents of HERO vilified transgender people as sexual predators and portrayed an ordinance protecting them as a “bathroom bill.” In so doing, they reframed a referendum question on civil rights as a question of whether to permit male sexual predators to molest children in women’s bathrooms. This strategy was dreadfully effective. On Nov. 3, Houston voters rejected the city’s anti-discrimination law by a 61-39 percent margin.

The conservative idea that civil rights protections sexually endanger women and children in public bathrooms is not new. In fact, conservative sexual thought has been in the toilet since the 1940s. During the World War II era, conservatives began employing the idea that social equality for African-Americans would lead to sexual danger for white women in bathrooms. In the decades since, conservatives used this trope to negate the civil rights claims of women and sexual minorities. Placing Houston’s rejection of HERO within the history of discrimination against racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women reveals a broader pattern: When previously marginalized groups demanded access to public accommodations, conservatives responded with toilet talk to stall these groups’ aspirations for social equality.

Since World War II, public bathrooms have figured centrally in African-American civil rights struggles for racial integration in the workplace and in schools. Integrating these spaces in the Southern United States meant doing away with Jim Crow laws that mandated, among other things, separate public bathrooms for blacks and whites. Whites defended these segregated spaces with violence. And, with varying degrees of cynicism, segregationists often interpreted demands for racial equality as black male demands for interracial sexual contact with white women. In 1941, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which prohibited “discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government,” the government established the Fair Employment Practices Committee to enforce this order. Historian Eileen Boris has shown how Southern Democrats fought the FEPC, viewing it as an attempt to “saddle social equality upon Dixie,” and lead to, in the words of one senator from Georgia, “social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races.”

While segregationists frequently claimed racial integration would grant black men sexual access to white women, white women also emphasized that contact with black women in bathrooms would infect them with venereal diseases. White women refused to share bathrooms with black women throughout the South and also in places like Detroit, which was flooded with white and black Southern transplants during the war years. Claiming that racial integration with blacks would cause them to catch syphilis from shared toilet seats and towels in public restrooms, white women engaged in numerous labor strikes and walkouts to resist FEPC policies. Their black co-workers doubtlessly faced harassment and intimidation throughout these conflicts. As Boris notes, “the toilet and bathroom, places for the most private bodily functions, became sites of conflict; their integration starkly symbolized social equality.”

Similar ideas played out before a national audience during the 1954 conflict over integrating Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas. Here again white women equated the threat of social equality with sexual disease. A white student reported, “Many of the girls won’t use the rest rooms at Central, simply because the ‘Nigger’ girls use them.” Again, the belief among white women that they would contract venereal diseases by sharing public bathrooms with black students was prevalent. Historian Phoebe Godfrey summarized the racial, gender, and sexual dynamics at play. Conflicts over bathrooms “were rooted in beliefs about the vulnerability of southern womanhood to blackness, which by its mere presence had the power to contaminate, symbolizing a sexual threat regardless of gender.”

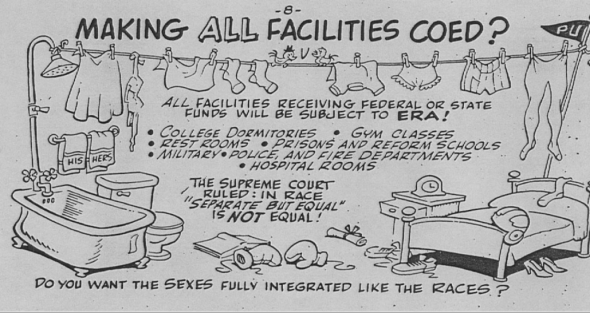

Graphic courtesy of the Hall-Hoag Collection of Extremist and Dissenting Printed Propaganda, John Hay Library, Brown University

By the 1970s, conservatives had transposed the racially and sexually charged image of bathrooms from African-American civil rights struggles to debates over the Equal Rights Amendment. Anti-ERA activists asserted that among the ERA’s consequences would be mixed-gender bathrooms. Here anti-ERA activists applied widely shared racial codes to the Equal Rights Amendment, particularly in their idea that the sex integration of bathrooms would lead to black sexual violence against white women and children. A cartoon booklet distributed by Phyllis Schlafly’s anti-ERA organization, the Eagle Forum, posed the following question meant to incite negative comparisons between the ERA and civil rights: “Do you want the sexes fully integrated like the races?” Referring to the ERA as enabling “sex mixing,” anti-ERA literature appealed to anti-miscegenation and anti-integration discourses.

The implications of this rhetoric unspooled in private correspondence and conversation. “I do not want to share a public restroom with black or white hippie males,” wrote one Floridian woman in 1973 to a Florida state senator. In North Carolina, a woman legislator overheard a male colleague state: “I ain’t going to have my wife be in the bathroom with some big, black, buck!” The intersection of race, gender, and sexuality was apparent to ERA proponents, including the legislative assistant to Florida’s governor. This assistant tried to explain these racial roots in a letter to one ERA opponent: “Many critics of the Equal Rights Amendment have used the idea of an ‘integrated’ restroom to illustrate their fear of the proposed Amendment. This idea comes from the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954.”

Dovetailing with conservative fears of gender and racial anarchy in bathrooms were widespread concerns about gay men having sex in public restrooms. In the postwar period, police monitored these cruising spots, known as tearooms, and regularly arrested and published the names of men who were having anonymous and consensual public sex. Among those ensnared by this policing was Walter Jenkins, chief of staff to President Lyndon Johnson, whose 1964 arrest made international headlines. Because police, medical authorities, and the media frequently depicted homosexuals as child molesters, public restrooms came to be understood as sites of sexual danger for young children. In 1954, a district attorney in Massachusetts prepared a leaflet “to protect children against crimes involving sex perversion” that contained tips for children such as: “Never wait or play around toilets. Always leave immediately.” The pamphlet circulated nationwide and police in Dade County, Florida, distributed it to 80,000 schoolchildren in 1954 alone. These same ideas also circulated widely through the antigay film Boys Beware (1959), which a former state attorney in Florida sought to have shown in every high school in Dade County during the 1960s.

Florida’s anti-gay history, which overlapped with conservative opposition to the ERA and African-American civil rights, is crucial to understanding what transpired in Houston last week. In the 1950s, the Florida Legislative Investigative Committee attempted to neutralize the African-American civil rights movement and sustain the state’s Jim Crow segregation. By the 1960s, it also focused on homosexuality and gay rights groups. FLIC oversaw anti-gay witch hunts on college campuses throughout the state while seeking to stymie the civil rights efforts of the NAACP. Its 1964 report, Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida, warned of the menace of gay men in public bathrooms. Not only did queers haunt restroom stalls, the report warned, they also, “posed a threat to the health and moral well-being of a sizable portion of our population, particularly our youth.” Homosexuals were more dangerous than the child molester, FLIC claimed, because victims of child molesters generally recover, “from the mental and physical shocks involved.” Homosexuals, however, “reach out for the child at the time of normal sexual awakening … to ‘bring over’ the young person, to hook him for homosexuality.”

By 1977, when Florida celebrity and singer Anita Bryant launched her infamous “Save Our Children” campaign, much of the rhetorical machinery vilifying gay men had already been put into place by anti-ERA and anti-civil rights campaigns, as well as by two decades of state-sponsored anti-gay activism. SOC embellished upon these ideas, dialing down the volume on racial dog whistles and playing up concerns about gender and sexuality. Bryant’s campaign also shifted the geography of the sexual threat, emphasizing the classroom and not the restroom. It then brought these ideas to bear on a local referendum in Dade County, Florida, on an ordinance that prohibited discrimination based on “sexual or affectional preference” in the areas of housing, public accommodations, and employment. Throughout the campaign, SOC hammered home the message that a civil rights ordinance meant homosexuals would be able to corrupt or molest children in schools. More, they claimed, the ordinance meant that if male teachers “were to show up in the classroom wearing a dress, that transvestite sexual behavior could not even be reprimanded by the school principal—because such a reprimand would violate the teacher’s ‘sexual or affectional preference’!” By characterizing a civil rights ordinance as an endorsement of homosexuals molesting children, the SOC campaign easily convinced Florida voters to reject the ordinance by a 69-31 percent margin.

Conservatives recognized a winning strategy and successfully applied the same template to municipal referendums across the United States in the late 1970s. Since the 1990s, similar sexualized child protection rhetoric—albeit absent the toilet imagery—drove conservative legislative drives to ban gay marriage. Recently, Proposition 8 in California and Question 1 in Maine spotlighted how conservatives continue to equate opposing gay marriage with saving children from sexual danger. All of which brings us to Houston. During the 2015 referendum, conservatives in Houston drew from sexual and toilet iconography that has been central to the conservative repudiation of minority civil rights for nearly 75 years.

Unlike most other public spaces in society, most Americans expect public toilets to be sex-segregated. Conservatives in Houston last week used this widespread expectation to stoke fears of transgender people whom they demonized as pedophiles. As with previous civil rights conflicts, conservative toilet talk in Houston presented an inverted image of power relationships. It portrayed members of dominant social groups as physically vulnerable in public spaces and imagined marginalized groups as powerful and threatening.

Conservatives reframed transgender demands for civil rights protections as sex offenders’ demands for sexual access to children. Child protection rhetoric thus distracted voters from the meaning of transgender activism and the systemic discrimination that transgender people experience. While there have been no reported incidents of transgender violence against women or children in public restrooms, violence against transgender people in public bathrooms abounds. Jodi L. Herman’s 2012 study typifies research on this issue. Herman found that 68 percent of transgender people she surveyed experienced verbal harassment, 18 percent had been denied access, and 9 percent experienced physical assault when trying to use gender-segregated public restrooms. Restroom violence is symptomatic of the broader forms of discrimination transgender people experience with alarming regularity. The history of conservative toilet talk reveals that rules governing access to and use of public restrooms is as much about our bodily functions as it is about the boundary making that has defined race, gender, and sexual relations in modern American society.

This post originally appeared on Notches: (re)marks on the history of sexuality, a blog devoted to promoting critical conversations about the history of sex and sexuality across theme, period and region. Learn more about the history of sexuality at Notchesblog.com.