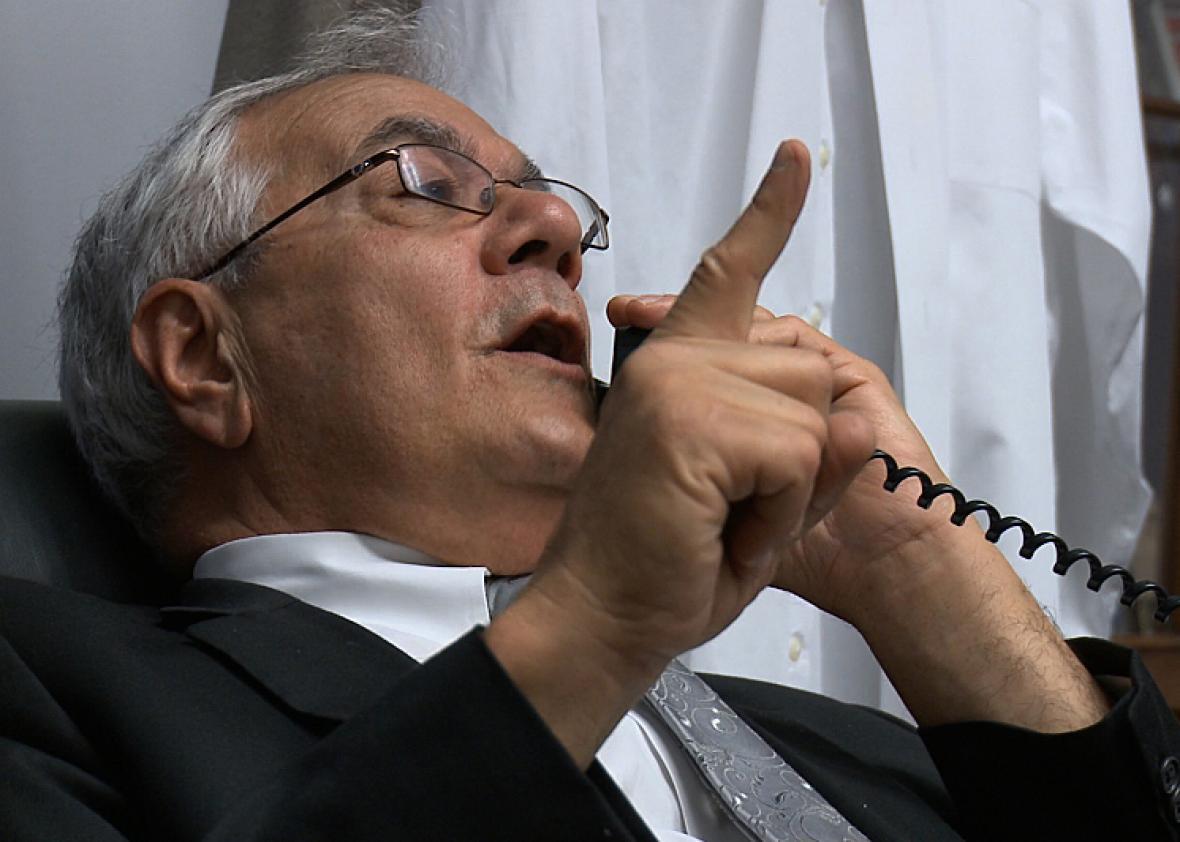

The guy who addresses the camera at the beginning of Compared to What? The Improbable Journey of Barney Frank, which premieres on Showtime Friday night, is a politician who has contested his last election. The D.C. drag of a professional shirt and tie has been replaced by a comfy-looking black T-shirt, he’s sporting a bushy retirement beard, and he says something no active pol could ever admit: He’d gotten tired of snapping to attention whenever a constituent called. “It was no longer ‘How can I help you?’ but in my mind, ‘Why are you bothering me,’ ” he admits.

That isn’t the only piece of his mind Barney Frank dispenses in the documentary, directed by Sheila Canavan and Michael Chandler.* He didn’t wait until retirement to dismiss questions he heard from journalists, members of the public, or fellow politicians as stupid. He’s smart and funny, and he apparently never saw the need to hide those traits from people who did or said dumb stuff in his presence. How could a guy this irascible have a career in electoral politics? He was obsessive, an astute strategic thinker, and had a gift for negotiation and deal-making. Still, as a young man he thought he was destined to be a consultant rather than the guy with his name on the ballot paper, because he was both Jewish and gay.

His Judaism proved not to be a barrier to getting elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1972 and to the U.S. House in 1980, but he didn’t immediately test the voters’ willingness to elect a gay politician. Although he’d known he was gay from the age of 13, he was deeply closeted. Even decades after he came out—somewhat reluctantly, after it became clear that former Republican Rep. Robert Bauman was going to out him in his book The Gentleman From Maryland: The Conscience of a Gay Conservative—it’s clear that Frank is still wrestling with the emotional distress he felt as a young man. He found the prospect of having his secret exposed “terrifying” and avoided relationships or sexual activity for many years. “Homosexuals were a despised minority,” he says, “I had no reason to believe that anybody would be anything but horrified” to learn that he was one.

Frank seems to have grown up with nothing but negative ideas about gay people. He felt “pressures to act in a very stereotyped way,” he says. As a young man, he apparently didn’t know any homosexuals worthy of his admiration, and he couldn’t even think of anyone gay “who was anything like the way [I] wanted to be.” There’s something tragic about this. After all, the homophobic era he grew up in was also a period of institutionalized racism, and yet Frank talks proudly of the way his father treated black customers with respect at his truck stop in Jersey City, New Jersey, and of his own trip to Mississippi to fight for black civil rights during the Freedom Summer of 1964.

Two years after he came out in 1986, Frank was “plunged into a scandal,” as the on-screen text puts it, when it was revealed that he had hired a male prostitute he was involved with to serve as his driver—and that the man (he isn’t named in the film) ran a prostitution ring out of Frank’s apartment. An investigation by the House Ethics Committee reprimanded Frank. He was able to hold on to his seat, but his hopes of holding a leadership role in the Democratic Party were over. Although he was open about his shortcomings, particularly his combative nature and his messy appearance (one of his early election slogans was “neatness isn’t everything”), he was proud of his reputation for honesty, right down to his unwillingness to suffer fools gladly. And yet his closetedness meant that there was “a central element of dishonesty” in his life—and it clearly caused him immense personal unhappiness on top of the public humiliation the scandal caused.

Although Compared to What? notes that Frank enjoyed an 11-year relationship with an economist starting in the 1980s, the contrast between his success as a legislator and the miserable state of his personal life is almost painful to witness. And he’s far from the only person to have suffered this way, of course. A few weeks ago, I chatted with Neal Baer, who is both a physician—he graduated from Harvard Medical School—and a successful TV writer and showrunner, having worked on China Beach, ER, Law & Order: SVU, and Under the Dome. In 2014, in his late 50s, he finally came out as gay—something he had known about himself since he was a teenager. Why did it take so long to share the secret with the world? “Shame,” Baer told me. “My journey was one of having to achieve as much as possible to deflect attention from who I am. There were never enough projects.”

Anyone who thinks that the closet is a thing of the past needs only to consider the pain that brilliant, high-achieving men like Baer and Frank brought upon themselves by their lies of omission or commission. And anyone who is considering the closet—or who, like young Barney Frank, can’t imagine a gay man who is anything like he wants to be—should watch the final section of the movie, which shows Frank’s wedding to Jim Ready, a butch, blue-collar, surfing, skiing dude. “Being gay was very disruptive in my life,” Frank says, but in his 70s, he has finally let go of the shame and is allowing himself to be happy.

* Correction, Oct. 23, 2015: The article originally erroneously referred to this documentary as a biopic.