It’s a well-known fact that artists often create their work in response to their life experiences—especially their upbringings. This is particularly true of Grace Jones, the iconic singer, model, muse, actress, and performance artist. Though she’s long been known for her fierce style and love of gender play, Jones grew up in an intensely repressive Pentecostal family in Jamaica. It was only when she moved to the United States that she began to test the limits—a path that would eventually lead to her breaking them down entirely. In this passage from her recently published memoir, Jones recalls her first encounter with gay culture via her brother Chris, and she offers her own view of how our categories of sexuality and gender can be as hindering as they are helpful.

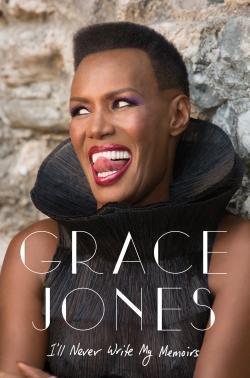

Excerpted from I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, by Grace Jones, out now from Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster.

I started to go out to the gay clubs with Chris. My dad was very uncomfortable at the time with Chris being gay. It was one of the worst things for a pastor to cope with in quiet, very repressed suburbia when you wanted your children to set an example for the religious community you were building, to appear pristine and deadly straight within the church family. Pentacostal Christianity is the kind of religion where you command no respect if your own family is seen as being different, or somehow stained.

It was difficult for Chris. It wasn’t necessarily a sexual thing—he was simply born very feminine. I felt as close as I could to Chris without us actually being twins. We easily passed ourselves off as twins, though, and I wonder if we were somehow tangled up inside my mother. I was born a little more masculine, a girl with some of the boyness Chris lacked. And he had some of the girliness I didn’t have. In Jamaica, this meant he got beat up and verbally abused a lot for being a “batty boy.” It’s changing now, there is more tolerance, but back then it was the dark ages.

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster.

There is a gene, I am sure, in your DNA that traps you inside a certain gender. For people like Chris, from the minute they can walk before they know anything, before they can speak, there is a definite feminine element in their movement. Chris was like that. He was teased because it wasn’t clear which way he turned. There is a world where he might have ended up conventionally straight and married. Girls, though, saw him as being too feminine to be sexually attractive, and a lot of straight men are attracted to pretty, young, feminine boys like Chris. Chris did admit to me that he was raped when he came to America by a straight family man. Chris was very delicate and feminine. It was tough for him. He played the organ at church, and I would call him “church gay,” or perhaps it should be “church feminine.” I think of Prince that way. A whole new gender, really.

He went to a psychiatrist, to try and sort out his feelings. He loved women. He could have had a girlfriend who understood his femininity, but if you are as feminine as he was, then the conclusion is, you must be gay. I don’t think that is necessarily the case. Sexuality can be much more fluid than that.

He was forced to choose, and to accept a specific sexual choice. He loved men, because of a fantasy father image he built while his father was away—also, straight men love him. And he was often attracted only to straight men. But then there’s no sex, so it’s very confusing for him. He walks and he swishes in a feminine way—he was born that way. But his direct sexual preference is not blatantly for men; he has gone with women whom he has had chemistry with. People would ask, Well, your brother is gay, how come he never got AIDS? Because he very rarely had sex, with a man or a woman! Closeness and friendship were more important to him.

Mom was much more understanding of his sexuality and tried not to put pressure him. My dad denounced him and stopped him playing the organ in church. Piano playing runs in the family, coming down from my mum’s dance-band dad, Dan, my real grandfather. Chris was an amazing pianist from the age ten, a prodigy. He played like the great Billy Preston at age eleven and used to contribute all the church music, help the choir—it was very important for him, this role. My father took that away from him because complaining church members were gossiping that he was gay. Chris was never the same when that was taken away from him.

He would say, “Well, if I’m gay I’ll do what gay people do.” And I’d go with him to the clubs. Being tangled up, having some of the man in me, I loved that. The man in me—as well as the girl—loved men! I felt I was among my own even as I was so far removed. This was when gay life existed deep in the margins of the margins of the mainstream, a system of rumors, innuendo, and scandal.

I would sneak a little drink, puff on a cigarette that would choke the life out of me, but those were merely early attempts to go out and discover a new world, meet people, different sorts of people, see what they did, good ones, bad ones. I didn’t feel disloyal to my parents. I’d been completely loyal to the family I had been given for a decade. It was time to be loyal to myself.

From I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, by Grace Jones. Copyright 2015 by Bloodlight, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.