As many critics have pointed out, Roland Emmerich sabotaged his new movie, Stonewall, by placing Danny, a fictional masculine, white savior, at its center. Many of the situations Danny is put in are clichéd and ridiculous, as is much the dialogue assigned to him. The best way to experience the movie is to imagine it without Danny, Garfield Minus Garfield-style. Absent his gee-shucks galumphing, however, the film is a relatively accurate representation of the events of June 28, 1969. The film’s cast of characters includes a mixture of real participants in the Stonewall riots and some composite inventions. Read on to learn who was real, who was invented, and who the composite characters’ lives were borrowed from.

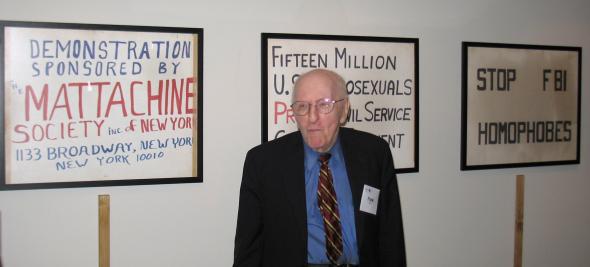

Frank Kameny

Photo by DCVirago, via Wikipedia

The film presents Franklin Kameny (Arthur Holden) as a suit-and-tie-wearing square who was a member of the early gay rights group the Mattachine Society—a group presented as uptight and Apollonian, in contrast to the more spontaneous, Dionysian queer kids who hung out around Christopher Street.* Kameny did coin the motto “Gay Is Good,” which is shown on a banner when he makes a speech in the movie—and he was indeed very uptight about the way gay people presented themselves. In his book Stonewall, Martin Duberman reports that Kameny believed conservatively attired gay protesters would be more likely “to get bystanders to hear the message rather than be prematurely turned off by appearances.”

The movie misrepresents Kameny’s views in one key respect, however. When Danny tells Kameny that he is interested in studying astronomy and becoming a civil servant, as the older man had done, Kameny tells him, “You’re going to have to find something else,” because gays can’t get government jobs. While it was true that homosexuals were then prohibited from federal employment (and many other lines of work); and that Kameny, who had a Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard, had been fired from the Army Map Service because he was gay; he would never have told a young man to abandon his career goals because he was gay. Kameny was tireless in fighting the ban—repeatedly challenging the Civil Service Commission until it formally renounced its no-homosexuals policy in 1975.

Ed “Skull” Murphy

Murphy (Ron Perlman), a bouncer-doorman at the Stonewall Inn, is the villain of the movie, which paints the former professional wrestler as a pimp, kidnapper, and blackmailer. The June 28 police raid was sparked by an Interpol investigation into bonds that Murphy was thought to have received from closeted Wall Street homosexuals as part of an extortion scheme, as well as a less glamorous crackdown because the bar was operating without a proper liquor license. As William McGowan explained in “The Chickens and the Bulls,” a chronicle of the extortion rings that preyed on gay men in the 1960s, Murphy had a long history of involvement with blackmailers who targeted gay men, though he later became an informant in the police investigation of a particularly vicious gang.

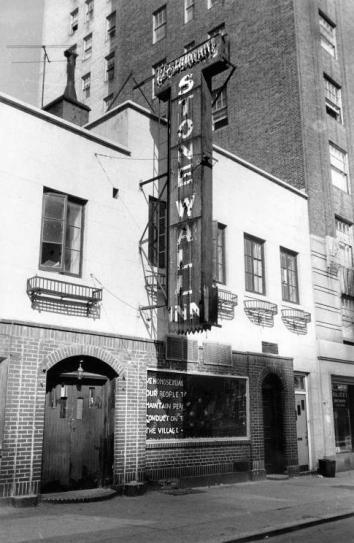

Photo by Diana Davies, copyright owned by New York Public Library, via Wikipedia

One of the movie’s most dramatically confusing and politically discomfiting scenes is Danny’s kidnapping and forced transportation to a swank uptown apartment, where he is serviced by Jay, a fat, old man in drag, who it is implied may earlier have killed a trick procured in similar circumstances. (In the film’s production notes, Jeremy Irvine, who plays Danny, says Jay “might stand for a very prominent American political figure.” He is probably supposed to suggest J. Edgar Hoover, though the stories about former FBI chief being a cross-dresser are almost certainly untrue.) Was Murphy really involved in such serious crimes? According to David Carter’s Stonewall, Murphy was widely suspected of involvement in the disappearance of a “masculine, good-looking Puerto Rican youth” who another young man saw being grabbed off the street in Greenwich Village and pulled into a dark car—a scenario very similar to the incident in the movie.

In the film, Murphy is handcuffed to Marsha P. Johnson when he is arrested in the police raid on the Stonewall; they flee the scene of the riots when corrupt cops allow him to escape (according to Duberman, the bar sent $2,000 a week in payoffs to the Sixth Precinct), then take a cab to a leather bar where the oddly clean-cut bartender removes the cuffs. According to Carter’s book, Murphy did get away from the Stonewall this way, though he was handcuffed to a young man named Frankie, not to Johnson.

For all his crimes against gays, Murphy was apparently beloved by street queens like Sylvia Rivera (one of the real-life inspirations behind the film’s Ray/Ramona character), who, according to Duberman, often turned to him for help. As McGowan noted, in the years after Stonewall, “Murphy earned prominence for working with people with AIDS, runaway teens, and young prostitutes, as well as homeless kids, addicts, and the mentally retarded.” He become a political activist and was eventually known as the “mayor of Christopher Street.”

The other real people portrayed in the movie seem flat and undeveloped. Marsha “Pay It No Mind” Johnson was a charismatic street queen and activist who co-founded STAR—Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, later renamed Street Transgender Action Revolutionaries—a political force that was also an informal support organization. According to Duberman, although there was no single inciting incident for the riot—that is, no equivalent of the brick Danny throws through the Stonewall’s window in the movie—during the protests Johnson did climb to the top of a lamppost and drop “a bag with something heavy in it on a squad car parked directly below, shattering its windshield.” Bob Kohler, a Navy vet who often socialized with the homeless queer kids while walking his dog, became a leading member of the Gay Liberation Front in the post-Stonewall era. Most historical accounts support the movie’s contention that unlike most of the cops of the Sixth Precinct, NYPD Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine was not taking payoffs from the Stonewall. In later years, Pine often spoke about the raid, including in the documentary The Stonewall Uprising.

The film’s composite characters are slightly more interesting, particularly Ray/Ramona (Jonny Beauchamp), the informal leader of the street queens, and political activist Trevor Nichols—though in the latter case, the disagreeable love rat’s biography is largely borrowed from the life of a heroic LGBTQ pioneer.

Ray/Ramona

Photo by Philippe Bossé

According to the film’s production notes, the main figures who make up Ray/Ramona’s character are baker Ray Castro, whose brutalization by the police during the Stonewall raid is reported to have stirred up the crowd outside the bar, and Sylvia Rivera, who in 1970 formed STAR with Marsha P. Johnson. Like the fictional Ramona, Rivera was alone in the world—her mother committed suicide when Rivera was 10, and her father was never in the picture. On June 28, 1969, according to Duberman, Rivera was in the small park across the street from the Stonewall when the raid started to go wrong.

Trevor Nichols

The most unfortunate borrowing from real life comes in the character of political activist Trevor Nichols (Jonathan Rhys Meyers). On his first appearance in the movie, Trevor is in the Stonewall, gathering information for his newsletter. He is active in the Mattachine Society; and after the first night of the riots, he is shown printing up flyers. Many of these biographical details were borrowed from the life of Craig Rodwell, who was politically active from the days when he first arrived in New York in 1958 to take up a scholarship at the School of American Ballet. He is perhaps best known for founding the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in 1967, the world’s first LGBTQ bookstore, which he ran until shortly before his death in 1993.

Like Trevor, Rodwell’s political activism sometimes involved writing—his newsletter the New York Hymnal was one of the first publications to forcibly denounce the Mafia’s control of the city’s gay bars. His review of the Stonewall said it had a “filthy john” and “high prices” and declared it “the tackiest joint in town.” Rodwell was active in the Mattachine Society, though he chafed at Kameny’s dress code, and on the Sunday morning after the raid, he really did compose a flyer, which he distributed at his own expense, despite his modest means. Where the movie shows Trevor standing back, appalled by the mob’s actions outside the Stonewall, Rodwell was in the thick of things. All reliable accounts note that Rodwell’s yell of “Gay power!” was a crucial rallying cry early in the protest. Duberman also notes that Rodwell had the foresight to alert the media about what was happening on Christopher Street: While the cops were still locked inside the bar, he ran to a phone booth and called the New York Times, the Daily News, and the New York Post.

The character of Trevor beds then quickly cheats on Danny and is disdainful of the street queens and of effeminate gays in general. In short, he is a dick. Though Rodwell’s name is never mentioned in the movie or in the film’s production notes, the borrowings are evident to anyone familiar with gay history. Emmerich and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz could easily have avoided assigning elements from Rodwell’s biography to such an unlikable character. Instead, they chose to sully the memory of a man who dedicated his life to the LGBTQ community.

*Correction, Sept. 25, 2015: This post originally misspelled Apollonian.