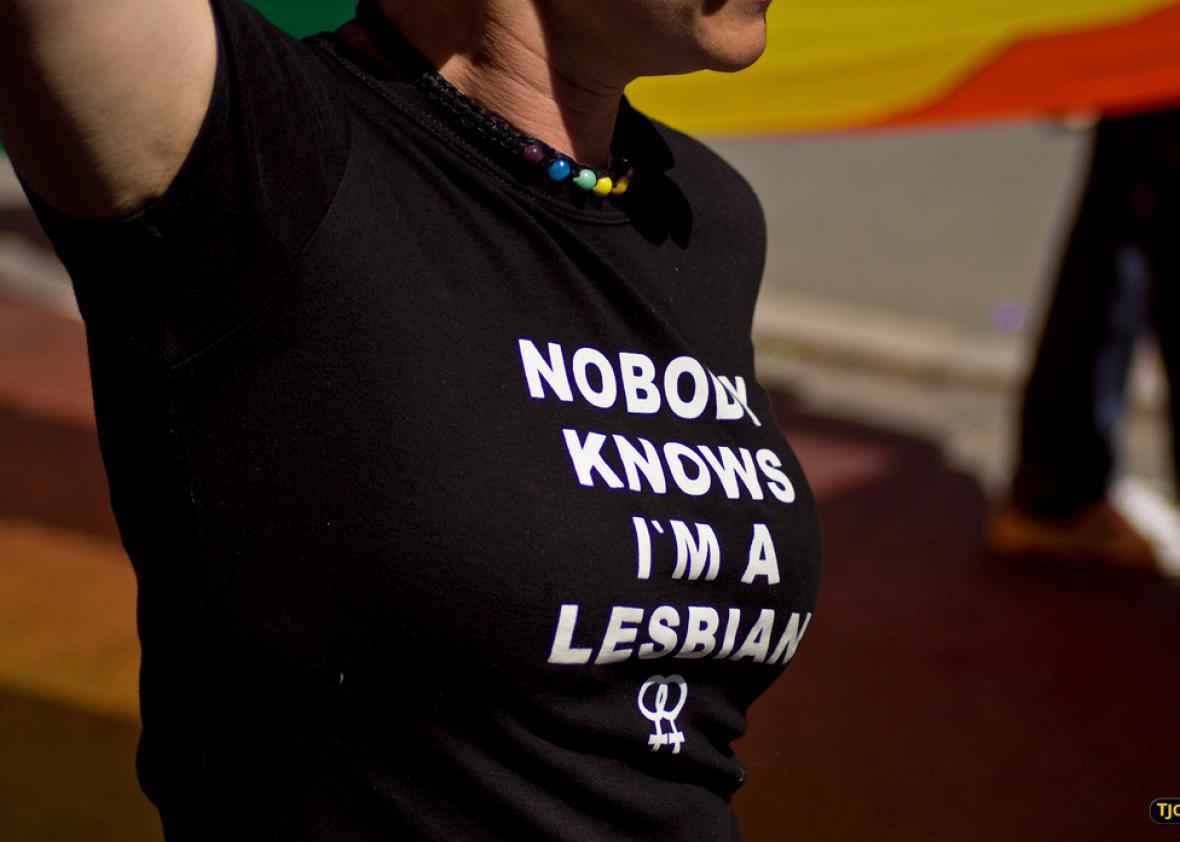

When South Carolina high-school student Briana Popour wore a T-shirt that read “Nobody knows I’m a lesbian,” she didn’t intend to offend anybody. But when Popour arrived at school wearing the shirt, administrators pulled her out of class and reprimanded her for being disruptive. Popour was given two options: Change her shirt, or go home. Popour refused to change. The school suspended her.

Now the school has relented, reversing its position that Popour’s shirt was “offensive and distracting.” The school district’s spokeswoman explained that “although the shirt was offensive and distracting to some adults in the building, the students were paying it little attention.” While the administration’s reappraisal is certainly good news, the entire incident reflects a troubling yet ubiquitous misunderstanding of students’ rights.

The Supreme Court’s most recent student-speech decision, 2007’s Morse v. Frederick, was a narrow ruling with a long shadow. Morse dealt with a student who unfurled a banner reading “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS” at a school-sponsored event. Since 1943, the court has afforded First Amendment rights to public schoolchildren. Since 1969, that protection has extended to highly controversial expression, so long as it doesn’t cause a “material and substantial interference with schoolwork or discipline.” Morse carved out an exception to that rule, holding that schools may restrict speech “promoting illegal drug use,” even if it’s not disruptive.

Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion went no further than that—but his rhetoric was casually dismissive of students’ rights, and lower courts have used Morse to give rank school censorship a pass. (Most outrageously, the 9th Circuit let schools ban American flag shirts on Cinco de Mayo.) These courts—and Popour’s school—seem to have forgotten that Morse came with a critical concurring opinion authored by Justice Samuel Alito and joined by Justice Anthony Kennedy. (The decision was 5-4, so the concurrence effectively limits its holding.) Alito wrote that school speech “that can plausibly be interpreted as commenting on any political or social issue” retains strong constitutional protection—even if the school asserts that such expression interferes with its “educational mission.” Schools may be allowed to regulate speech encouraging drug use. But they remain constitutionally barred from censoring most speech that doesn’t endorse illicit conduct.

In light of Alito’s concurrence, Popour’s suspension was obviously illegal. Her shirt was both an expression of her own sexual identity and an ironic commentary on LGBTQ visibility. It’s exactly the kind of speech the First Amendment was designed to protect, in or out of school. If Popour is still perturbed by the infringement of her clearly established constitutional rights, she should consider suing her school district. It might not make up for the injustice she suffered. But it’ll send a clear message to public schools across the country that, yes, students have a right to express their sexual orientation—even on a goofy T-shirt in a high-school classroom.