Now that no-smoking signs decorate most public spaces, and anti-tobacco PSAs are a health class staple, it’s no surprise that tobacco use is on the decline. Yet for one group of Americans, smoking is still remarkably common. According to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, LGBTQ individuals are more than 33 percent more likely than non-LGBTQ people to smoke cigarettes—leading to elevated risks of stroke, heart disease, and lung cancer.

Researchers have blamed queers’ higher smoking rates on a variety of factors, including the daily stress of coping with prejudice and stigma. Yet while stress has indeed been correlated to tobacco use, it’s not the entire story. Over the last 25 years, several major cigarette companies have also launched strategic ad campaigns aimed at the LGBTQ community. By positioning themselves as allies to the gay rights movement, these corporations have worked relentlessly to make smoking an accepted part of queer culture.

In 2000, R.J. Reynolds—the parent company of Camel, Pall Mall, and several other popular cigarette brands—sparked controversy when confidential documents labeled “Project SCUM” (SubCulture Urban Marketing) were leaked to the press. The documents outlined plans for an ad campaign targeting two distinct “consumer subcultures” in San Francisco: young gay men in the Castro and the homeless in the Tenderloin.

The documents outraged many community leaders, who saw the project’s title as evidence of the company’s homophobia. “They just see us as another set of disposable consumers to addict and dehumanize,” gay rights and anti-tobacco activist Bob Gordon told the San Francisco Weekly following the leak.

Publicly, however, Reynolds made every effort to express support for queer customers. Camel hosted a booth at the 2000 San Francisco Pride parade, and sponsored an after party at a popular gay nightclub. More recently, a 2011 Camel Snus ad encouraged queers to “take pride in your flavor.”

And Reynolds is not the only cigarette company that has reached out to LGBTQ customers by promising solidarity—or, at least, the appearance of it. In 2001, Lucky Strike placed several ads in the program for the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation Media Awards. The messages looked more like PSAs than advertisements, featuring taglines like “When someone yells, ‘Dude, that’s so gay,’ we’ll be there.”

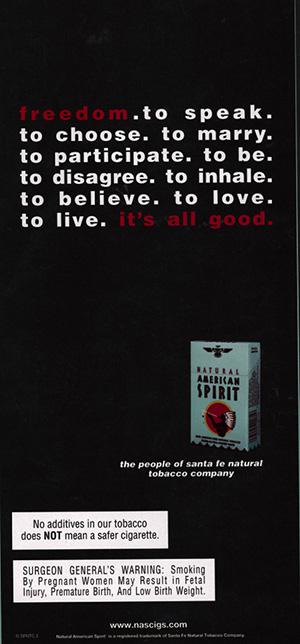

Advertisement by American Sprirt via LGBT Tobacco

Other ad campaigns have targeted queer customers more covertly by co-opting the language of freedom and choice used by LGBTQ rights activists. In 2001, a Lucky Strike spread featured a lesbian couple along with the phrase “I Choose.” And in 2005, American Spirit—a Reynolds subsidiary—launched an ad listing various “freedoms,” including “freedom to choose” and “freedom to marry” along with “freedom to inhale.”

Over the last few years, anti-tobacco legislation has greatly restricted how and where tobacco companies can advertise. Yet while tobacco ads may be on the decline, their legacy continues to impact the queer community. According to the CDC, 1 in 4 LGBTQ adults currently smokes, compared with 1 in 6 straight adults. And in certain areas, such as New York City, LGBTQ youth are as much as twice as likely to smoke as their straight peers.

Why, then, have marketers singled out an already marginalized community to sell a product that is known to be harmful? One explanation has to do with mental health. LGBTQ individuals are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than non-LGBTQ people, both of which are major predictors of tobacco use. This phenomenon has likely contributed to queers’ elevated smoking rates—and made LGBTQ youth a prime target for advertisers.

But there are other reasons queer teens are attractive customers for tobacco companies. For decades, cigarettes have been a symbol of counterculture and disrespect for conservative norms. As New York Times columnist Tina Rosenberg noted in 2012, for teenagers, “a cigarette is not a delivery system for nicotine. It’s a delivery system for rebellion.” And while teenage rebellion is by no means exclusive to queers, LGBTQ teens have plenty of reasons to want to rebel from a society that has ostracized them.

The tobacco industry has directly played to many young queers’ experience of oppression. Using buzzwords like freedom and choice, cigarette companies promise LGBTQ teens exactly what a widely homophobic, trans-phobic culture doesn’t. The fact that this “freedom” comes packaged in a gesture of defiance only adds to its appeal. Unlike other cigarette ads, these campaigns don’t sell teen outcasts an opportunity to be cool, or to fit in. They sell them an opportunity to be outcasts, but also to be empowered—a chance to embrace their identity as outsiders and blow smoke in the face of the society that cast them out.

Despite their pro-gay advertisements, however, the tobacco industry has hardly been an ally to the queer community in practice. While Marlboro parent company Philip Morris received press attention in 1991 for its donations to HIV/ AIDS research, the LGBTQ anti-tobacco site socrush.com reported that cigarette companies provided two to three times more support to politicians opposed to gay rights than those for them. In the end, it seems Gordon was right: For Big Tobacco, queers are simply another convenient group of consumers.