Every schoolchild knows that in 1954 Brown v. Board of Education overruled Plessy v. Ferguson, the infamous 1896 separate-but-equal case, but every expert knows that Brown did no such thing. Earl Warren’s landmark opinion contained no sentence saying, “Plessy is hereby overruled.” Brown did not even say that Plessy was wrongly decided. Warren’s watershed Brown opinion merely said that Plessy was a case about segregation in transportation—railroads—and that Plessy’s separate-but-equal doctrine did not apply to the field of public education. The lesson here is that at least for certain world-historical, once-in-a-generation rulings, the basic rightness of the court’s result within the broad sweep of human affairs—the court’s success in seizing the moment and doing the right thing—sometimes overwhelms the precise language of the court’s exposition. To bend a phrase from Lincoln, in some of the biggest battles the world may little note nor long remember what the court said, but it will never forget what the court did.

The June 26 ruling on same-sex marriage is the closest the court has ever come to a repeat of Brown. Of course, no two cases decided decades apart on different issues could ever be identical in every respect—Heraclitus taught us long ago that one never steps in the same river twice. But there are obvious parallels between Obergefell v. Hodges and Brown v. Board. Brown’s deepest thrust was to proclaim the dignity and equality of black Americans, and Obergefell is likewise a powerful and profound affirmation of the dignity and equality of gay Americans. Beyond equality, the two cases celebrated the substantive and symbolic significance of bedrock societal institutions. Brown was an ode to education, and Obergefell is an ode to marriage. Brown’s majority opinion crossed party lines. A Republican appointee spoke authoritatively for the court with not a crack of daylight between him and any of the court’s Democrat appointees—no divisive dissent or distracting concurrence from any of the justices from the other side of America’s partisan divide. Ditto for Obergefell.

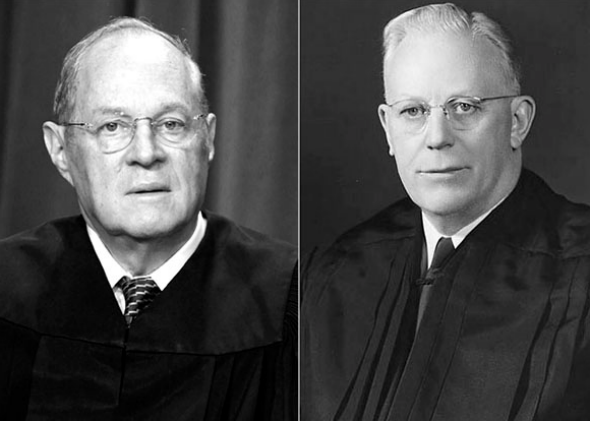

Surely these and many other similarities were not lost on the author of Obergefell, Anthony Kennedy, who grew up in the shadow of Earl Warren. As a youngster in Sacramento, California, Kennedy worked after school in the state house, when Warren was governor. “I knew Earl Warren very well,” Kennedy said in a 2005 interview. “[I] knew his children and played in the governor’s mansion.” Warren was famously bipartisan, a fact not lost on Kennedy, who in that same interview highlighted the fact that, as an incumbent governor in 1946, Warren “ran on both the Democratic and Republican tickets.” Warren is the only person in California history to accomplish this feat; analogously, Kennedy is the only current justice who routinely sides with Democrat appointees in many key cases and with Republican appointees in many other key cases. (Recall that, although appointed to the Supreme Court in 1987 by a Republican president—another famous California ex-governor named Ronald Reagan—Kennedy had to win confirmation in a Democrat-controlled Senate that had just nixed Reagan’s earlier nominee, Robert Bork.)

Because this swing justice truly swings, and at times openly broods on which way he should swing, some consider Kennedy a judicial version of Hamlet. If so, Earl Warren is Hamlet’s ghost, a judicial father figure whom Kennedy sees in his mind’s eye. In a landmark 1992 decision, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Kennedy co-authored a section of the court’s opinion that detoured to ponder the relationship between Brown and Plessy, even though the case at hand involved abortion, not race. Four years later, in Romer v. Evans, the first major Supreme Court victory for gay rights, Kennedy spoke for the court to condemn a Colorado referendum that openly bashed persons of “Homosexual, Lesbian or Bisexual Orientation.” Romer was decided exactly 100 years, to the week, after Plessy v. Ferguson, and this disgraceful case—the case Warren would powerfully undermine (though not quite overrule) in Brown—was once again on Kennedy’s mind. He opened as follows: “One century ago, the first Justice Harlan [in his now canonical Plessy dissent] admonished this Court that the Constitution neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

In the opening minutes of the April 28 oral argument in Obergefell, it was Kennedy who, unprompted, explicitly invoked Warren’s two most famous decisions on race: Brown v. Board and Loving v. Virginia. Loving, of course, was the 1967 landmark case in which Warren struck down a state law banning racial intermarriage. Warren grounded his ruling on two principles, equality and a fundamental (albeit unenumerated) right to marry—the same two principles that Kennedy himself would intertwine in his majority opinion in June.

In Obergefell, Kennedy wrapped himself in Loving, citing it approvingly almost a dozen times. The only opinion that Kennedy favorably mentioned more often (barely) was his own majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 case striking down state sodomy laws—an opinion that, according to Justice Antonin Scalia’s angry and self-fulfilling dissent that day, portended a right to same-sex marriage. And as Kennedy himself noted on April 28, in another line full of portent, the time span between Lawrence and Obergefell roughly matches the 13-year gap between Brown and Loving.

Noting the rhetorical contrast between Warren’s spare style in Brown and Kennedy’s fondness for sweeping and soaring prose, some legal commentators have faulted Kennedy’s grandiosity and self-importance. But perhaps Kennedy is simply more honest about the court and the world beyond. Whereas Warren pulled his punches in Brown, Kennedy speaks openly and passionately (yet politely) of the demeaning aspect of the laws he strikes down. And Kennedy’s supercharged vision of judicial power is just what one might expect from a youngster who grew up watching Earl Warren lead America and the court into the history books.

The biggest difference between Warren and Kennedy is that Warren spoke for a unanimous court. But Warren had all the formal advantages and trappings of the chief justiceship; Kennedy does not. Warren did not have to contend with the operatic diva known as Antonin Scalia. And most important, Warren’s world was not deeply and pervasively split along partisan lines. In 1954, there were many liberal Republicans and many reactionary Democrats in America.

No more—and no more in large part because of Brown and Loving. Once race leaped onto the midcentury American agenda, Congress eventually had to choose sides. When, led by President Lyndon Johnson, Congress sided with Brown’s vision of racial justice in a series of civil-rights and voting-rights laws, grateful Southern blacks surged into the Democratic Party. Conservative southern whites, encouraged by Republicans Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, abandoned the Democratic Party to become Republicans. The party of Lincoln became the party of the Confederacy, pushing liberal Northern and Eastern Republicans out of the party. Today, the realignment begun by LBJ, Goldwater, Nixon, and the Warren Court has resulted in near perfect polarization. On almost every issue in Congress, the most conservative Democrat is still to the left of the most liberal Republican. Almost no one in high elective office truly swings, mediating between America’s two entrenched political parties and their sharply differing worldviews.

This is all the more reason to celebrate rather than to mock Anthony Kennedy, one of America’s last remaining Lincoln Republicans, who hails from gay-friendly Northern California and hearkens back to an earlier Lincoln Republican named Earl Warren.

This is the first of two Slate articles on Obergefell. In his follow-up piece, Amar will analyze the Obergefell dissents and offer his own version of what an ideal Obergefell opinion should have said. For more on Justice Kennedy as a Northern Californian Lincoln Republican, interested readers may wish to consult Chapter 4 (“Anthony Kennedy and the Ideal of Equality”) of Amar’s latest book, The Law of the Land: A Grand Tour of our Constitutional Republic. Chapters 3 and 5 of the book feature more material on Brown and on the geographic and partisan realignment it helped precipitate.