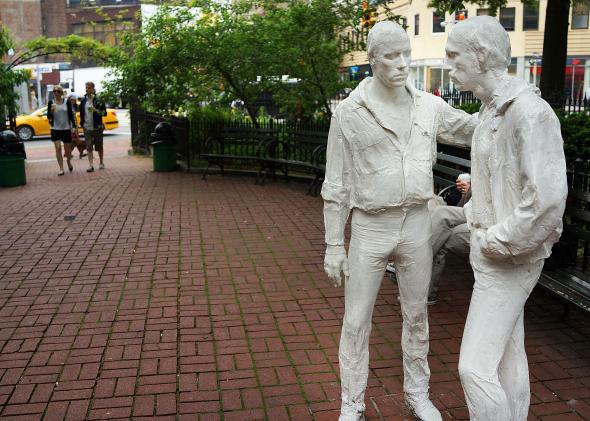

Walk along Waverly Place in New York City’s West Village and you’ll hit the narrow end of Christopher Park, a sharp shard of public land inhabited by four lovely but melancholy figures. Covered in white plaster, they are clustered in pairs: two men, standing, and two women, seated. They’re called “Gay Liberation”—but there’s nothing liberatory about them. With their mournful expressions and restrained physical contact, they seem more like a vision of gay tolerance, liberation’s anemic shadow.

The artist who made them, George Segal, was known for creating these white plastered sculptures, which made for powerful silent monuments to the Holocaust and the Kent State Massacre. But that quiet solemnity fails here. These pairs of gay men and lesbians seem more depressed than liberated. Their mild physical affection seems at most avuncular, like the firm yet inhibited shoulder squeeze you might give a co-worker who just found out they have cancer. This is liberation of the most limited kind, the sort that frees you to live alone with your cat or your collection of Broadway cast albums.

But often, this is the only publically acceptable face for homosexuality: neutered, safe, and perfectly indistinguishable from a straight person. I’m not saying that nattily-dressed, “proper” men and women have no role in gay liberation. If you want to see some respectable revolutionaries, just look at the photos of Kay Tobin Lahusen, the letters of Lorraine Hansbury, or the protests of the Mattachine Society. After decades of being told they were inherently disordered or intrinsically immoral, their very normality was, in and of itself, a radical act—a way of announcing “we are everywhere.”

But those statues sit in Christopher Park to commemorate the Stonewall Rebellion, an anti-police-harassment riot led by nelly chorus boys, outspoken trans women like Marsha P. Johnson, and old-school butch dykes—the people black lesbian feminist scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs calls “the never straight.” At Stonewall, as is often the case in moments of police violence, it was those with the least social capital (the poor, the genderqueer, and the people of color) who fought back. They are the ones who can’t (or won’t) pass, assimilate, or hide. They are the most likely to be abused and the least likely to be memorialized. They are the ancestors who paid the price for our freedom—and they’re still paying it today (or perhaps you haven’t heard about the string of murders and suicides that have rocked the trans community this year).

The movement for LGBTQ rights has spent decades tacking between two poles, one that asks for tolerance and another that demands liberation. Tolerance means being accepted based on how convincingly you can wear the drag of the mainstream; liberation means being accepted on your own terms. It is dangerously easy to confuse one for the other—indeed, it seems many of us make that mistake daily. Today, gays can serve in the military, and very soon the Supreme Court is likely to legalize same-sex marriage across the country. I won’t argue that these rights aren’t important, but look at what we still don’t have: In 28 states, discrimination based on sexual orientation is still legal, and in 31 states, it’s legal to discriminate against transgender people. This is the line between tolerance and liberation: Whether you have the freedom to be like everyone else, or the freedom to be yourself.

At a time when our country is once again rocked by riots demanding justice from a broken system, it’s critical that we celebrate not just the sterile concept of liberation, but its messy reality. Chains don’t break themselves, and they don’t go quietly. By reducing the shouts of gay power to the whispers of tolerance, we prevent ourselves from understanding what it takes to actually make change in this world. If, in the West Village in 1969 liberation looked like a quiet conversation, as Segal’s statues suggest, how can we understand Baltimore or Ferguson or even Zuccotti Park? How can we be prepared for the next time we need to take to the streets—or even know when that moment arrives? How can we prevent ourselves from being held up as the new “model minority” and used as a stick against communities that are fighting for their freedom today?

Public memorials should help us remember and understand our history, so that we can use it to guide us to a better future. Segal’s sculpture was controversial in its day; so much so, in fact, that it took years to overcome protests and have it installed. But now it sends the wrong message. Where is the sculptor who will show us what liberation looks like today? Where is the monument that will guide us toward more freedom, for more people? It is no easy task to physicalize the joy and power that come with freedom, while simultaneously leaping over the pitfalls of representation to speak broadly to the LGBTQ community—but surely some sculptor is up to the challenge.

Want to hang out with Outward? If you’ll be in or near New York City on Monday, July 13, join June Thomas, J. Bryan Lowder, and Mark Joseph Stern—and special guests Ted Allen, of Queer Eye and Chopped fame, and marriage equality campaigner extraordinaire Evan Wolfson—for a queer kiki at an Outward LIVE show, hosted by City Winery. Details and tickets can be found here.