Pioneers of the struggle for LGBTQ civil rights are often celebrated these days, as injustices of the past and present are beginning to be rectified. Brave men and women who sacrificed their privacy and all too often exposed themselves to homophobic abuse from the state and the general public in an earlier, less tolerant era regularly appear at fundraising dinners and celebratory rallies. Often old and sometimes frail, they are enthusiastically applauded, even when those of us in the audience don’t know much about what they went through on their way to the podium.

Limited Partnership, a documentary film that makes its debut on many PBS stations Monday night as part of the Independent Lens series, is a powerful corrective to the historical ignorance many of us exhibit. By showing the 40-year struggle of one binational gay couple to have their relationship recognized so they could legally stay together in the United States, we are reminded just how ugly the system was until astonishingly recently.

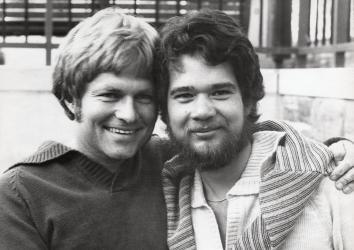

Photo by Pat Rocco

Richard Adams and Tony Sullivan met in 1971 at a Los Angeles gay bar called The Closet. Adams had come to the United States from the Philippines with his family at the age of 12 and eventually became a U.S. citizen; Sullivan was an Australian on one of those globetrotting vacations his compatriots are known for. At the time, homosexuality was a potential cause for exclusion from the United States, but when the two men fell in love, Sullivan maintained his immigration status by crossing the Mexican border and re-entering the United States every three months. It wasn’t a sustainable strategy. Binational straight couples had a path to legal residence and eventual citizenship through marriage, but no such option was available to same-sex couples. Then in 1975, two men asked Clela Rorex, a county clerk in Boulder, Colorado, for a marriage license, and she could see no legal reason to deny them. Rorex issued licenses to six same-sex couples, including Adams and Sullivan, before Colorado’s attorney general declared that same-sex marriage was illegal.

When, after their marriage, Adams applied for a green card for Sullivan, he received a response from the immigration authorities that declared, “You have failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” This was shocking, but Sullivan found a silver lining in the unhappy news: “I knew decent people would be shocked,” he says. On TV shows ranging from Donahue to Today, the two men maintained a remarkable dignity in the face of vile hostility: They refused to be separated and had faith that at some point the system would confer the same rights and respect to their relationship that it bestowed on heterosexual couples’ unions.

That point was not 1985, however. When the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals considered the petition for Sullivan’s deportation to be suspended (a lower court had declared that it would “cause no emotional hardship” for the men to be separated), Associate Judge Anthony Kennedy—yes, that one—wrote that leaving the country would bring “no extreme hardship” to Sullivan because he was not “a qualifying relative to Adams.”

You should watch Limited Partnership to see what happened next, though it will perhaps comes as no surprise that the legal and governmental systems emerge looking bigoted and heartless in their treatment of this couple, who, it should be noted, represent the plight of tens of thousands more who faced separation over the four decades their story plays out. What is unusual is that Adams and Sullivan spoke to numerous journalists, documentary filmmakers, and TV talk show hosts over the course of many years, which provides director Thomas Miller with an astounding cache of photos, interviews, and papers to document their fight for equal rights.

As we wait for the Supreme Court to announce its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the mood is generally optimistic that the big-picture story will have a happy ending. Can the same be said of Adams and Sullivan’s story? I won’t spoil the final 15 minutes of Limited Partnership, but it’s no spoiler to say that it leaves no doubt that theirs is the kind of relationship—the kind of love—that deserves recognition.