At first glance, Kerry v. Din looks like a minor case about a straightforward issue. Fauzia Din, a U.S. citizen, asked the government to give her husband, an Afghan citizen, a visa. The government refused. But rather than give a specific reason for the rejection, the government told Din only that the visa was denied because her husband partook in “[t]errorist activities.” Din sued, claiming that if the government wants to keep her apart from her husband, it has to give a more specific reason. On Monday, the court held that the reason the government gave was good enough.

Yet just beneath the surface of Din lies a roiling intramural debate over marriage, liberty, and the dictates of due process. Four justices held that the “liberty” protected by the due process clause requires the government to clearly explain its reasoning when it deprives someone of her ability to live with her spouse in America. Three justices held the due process clause requires no such thing. Two justices simply assumed that it does—then found that the government gave Din a satisfactory explanation.

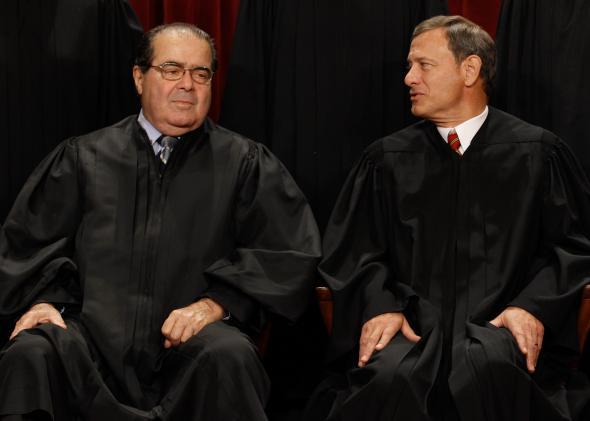

The real action here lies in the war between Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion (joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Clarence Thomas) and Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent (joined by the other three liberals). Breyer writes that Din has a constitutionally protected “liberty interest” in “liv[ing] together with her husband in the United States.” As Breyer explains:

[T]he institution of marriage, which encompasses the right of spouses to live together and to raise a family, is central to human life, requires and enjoys community support, and plays a central role in most individuals’ “orderly pursuit of happiness.”

Thus, if the government infringes upon this liberty, it must provide her “due process”—“a statement of reasons, some kind of explanation, as to why” it denied her husband’s visa.

Scalia comes charging out of the gate against Breyer’s assertion that Din holds a constitutional right “to live in the United States” with her husband. “There is no such right,” Scalia flatly declares. He then spurns the very idea that the liberty protected by the Constitution encompasses a wife’s right to reside with her husband. There is no “free-floating and categorical liberty interest in marriage,” Scalia maintains. The government is therefore free to infringe upon a married couple’s ability to live together with essentially no procedural due process.

If this debate sounds familiar, that’s because it’s also at the heart of Obergefell v. Hodges, the gay marriage cases that have embroiled the court this term. There, too, the liberal and conservative blocs of the court are at war over the meaning of constitutional liberty. Admittedly, the precise point of contention is slightly different: In Obergefell, the plaintiffs are arguing that marriage is a fundamental right, which the government cannot prohibit; in Din, the plaintiff argued that marriage includes the liberty to live together. Still, the contours of the debate are strikingly similar in each case. At bottom, the plaintiffs are asking the court to extend constitutional liberty far beyond mere bodily freedom—to the most intimate realm of personal relations.

With that backdrop in mind, the justices’ respective votes in Din take on a tea leaf-ish quality. It’s no shock that the four liberals voted to expand constitutional liberty or that Scalia and Thomas voted to restrict it. The real surprise here is Roberts, who casts his lot with Scalia and Thomas to find no constitutional protection for spouses who wish to live together. If Roberts won’t grant Din even this pinch of procedural protection under the due process clause, he’s quite unlikely to find a broad due process right for gay couples to marry.

Unfortunately, Din reveals nothing about the Obergefell swing voter, Justice Anthony Kennedy. In an opinion joined by Justice Samuel Alito, Kennedy declines to enter the marriage brawl. Instead, Kennedy writes even if Din has a constitutional right to know why the government is keeping her spouse out of America, that right was fulfilled by the government’s terse justification for rejecting her husband’s visa. Kennedy—who relishes opacity—abstains from expounding upon the meaning of constitutional liberty in the context of marriage.

Does Roberts’ vote in Din prove that Roberts is certain to vote against marriage equality? Not quite. Din forecloses any possibility that Roberts would find a fundamental right in the due process clause for gay couples to wed. But marriage equality advocates have an even better argument in their arsenal—that the equal protection clause bars states from excluding gays from marriage. If Roberts wants to join the liberal bloc in Obergefell, the equal protection route remains open to him.

As a matter of Supreme Court Kremlinology, the most interesting aspect of Din isn’t Roberts’ vote. It’s Scalia’s tone. Scalia is notorious for throwing temper tantrums toward the end of every term when big cases don’t go his way. He tends to channel his fury into his dissents in other cases, especially those tangentially related to a blockbuster he lost. In 2012, Scalia’s anger over the Obamacare decision seemed to infect his dissent in the Arizona immigration case. (Both cases dealt with federal power.) And in 1990, Scalia penned a weirdly vicious opinion in an obscure personal jurisdiction case, spilling quarts of ink over the meaning of due process. As it turns out, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor had just cast her first ever vote striking down an abortion restriction—citing the due process clause.

Scalia’s irate Din opinion could have nothing to do with the marriage equality cases. It might just be Nino being Nino. Or it could be the justice’s accidental indication that the court will rule in favor of marriage equality in just a few weeks.