Consider for a moment what would have followed if the Supreme Court had left laws that prohibited interracial marriage “up to the states.”

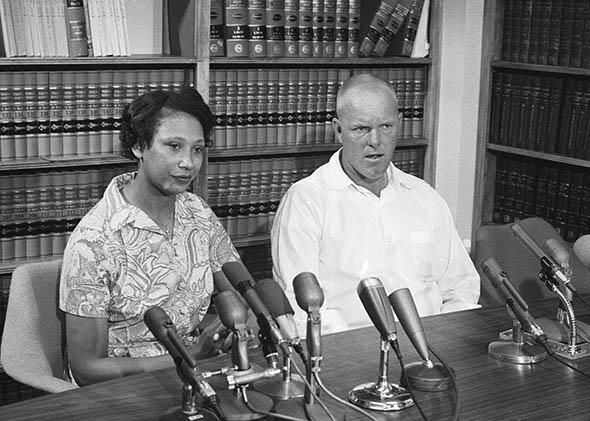

This is a perfect time for such reflection, as June 12, 2015, marks the 48th anniversary of the court’s historic ruling in Loving v. Virginia, a unanimous decision that struck down the laws of Virginia and 15 other states that in 1967 still prohibited interracial couples from marrying. Loving is of particular relevance right now, with the court soon to decide, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the fate of state laws that deny same-sex couples the freedom to marry. Most important, of course, and as I’ve discussed elsewhere, is the fact that Loving provides two independent bases for the court to invalidate those laws. One is that they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equality under the law to all persons, and the other is that they also deny gay men and lesbians the fundamental right to marry.

But Loving is also important because it debunks a key argument the states defending their discriminatory marriage laws have made to the court in Obergefell, namely, that marriage equality for same-sex couples should be decided by state voters or state legislatures. According to defenders of these laws, the “democratic process,” not the courts, should determine the issue. This argument is wrong—in our system of federalism, the U.S. Constitution is the supreme law of the land, and the fundamental rights of minorities are not subject to a majority vote. Loving is an excellent example of why.

When Loving was decided in June 1967, nearly one-third of the states in this country prohibited an African American from marrying a white person. That’s right, in 1967. Indeed, it was only 19 years before Loving was decided that the first state court—the California Supreme Court—held that state’s ban on interracial marriage to be unconstitutional. And while 14 states repealed their own laws in the intervening two decades, 16 states were still clinging to their interracial marriage bans in June 1967. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that a majority of Americans “approved” of interracial marriage. These examples alone show why our governmental system wisely does not leave the constitutional rights of minorities up to the whims of a majority vote but instead obliges the courts to step in when those rights are violated.

Of course, there’s no way to know how long those 16 states would have continued to ban interracial marriage absent the ruling in Loving, but it’s a good bet that in some of them, there was no quick end in sight. The history of just one, Alabama, provides good evidence of that. After the court’s ruling, the affected states began to remove the now-unenforceable but still offensive interracial marriage bans from their state codes and constitutions. Astonishingly, however, the remaining years of the 20th century ticked away and still the Alabama Constitution proclaimed that, “The legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any marriage between any white person and a Negro, or descendant of a Negro.” In 1998, a measure that would have set in motion the repeal of that language “died in a legislative committee.” Died in committee in 1998!

Meanwhile, that same year, South Carolina left Alabama as the only state with an interracial marriage ban still on the books, removing its own state constitutional provision by a vote of the electorate. Even so, 38 percent of those voting opposed amending the South Carolina Constitution, preferring to keep the provision that declared, “The marriage of a white person with a Negro or mulatto … shall be unlawful and void.”

In 1999, the Alabama legislature finally sent to that state’s voters a proposed constitutional amendment to repeal the state charter’s ban on interracial marriage, although, according to CNN, “[s]ome members of the House panel reportedly balked at approving the interracial marriage bill until they were assured it would not open the door for homosexual marriages in the state.” The proposal was adopted by the voters in November 2000, and Alabama thus became the last state in the country to rid its books of a ban on interracial marriage, although, as in South Carolina, a substantial minority of Alabamians voting on this measure – 40 percent – wanted to preserve the ban, unenforceable as it was.

Fast forward to the present day, and we find Alabama now fighting tooth and nail to keep same-sex couples from marrying. Although federal Judge Callie Granade (a George W. Bush appointee, by the way) earlier this year held the state’s prohibition of same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional, the Alabama Supreme Court ordered the state’s probate judges not to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. While Judge Granade has made it clear that her ruling applies statewide, she has put it on hold pending the decision in Obergefell. Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore (who has a history of constitutional defiance) has been particularly vociferous in fomenting resistance to Judge Granade’s ruling and has even suggested that U.S. Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan should be impeached for having officiated at the weddings of same-sex couples.

Whether same-sex couples in Alabama and 13 other states around the country will continue to be denied the freedom to marry is now up to the U.S. Supreme Court. As Loving shows, this country will always have constitutional outliers when it comes to respecting the fundamental rights of minorities, and that’s where the courts come in. In Loving, as it has in many other cases, the Supreme Court fulfilled its constitutional role as the ultimate guardian of those rights. It must now do the same in Obergefell.