“One of the reasons I’m here right now is because I stuck to my guns and kept making the same kind of crazy, low-budget films, you know?”

I’m sitting with noted queer-punk provocateur Bruce LaBruce at The Modern, a swanky, fine-dining destination adjacent to the Museum of Modern Art. In a few moments, he’ll be whisked away by the MoMA’s film cognoscenti to introduce an unprecedented 10-day retrospective of his work. To mark the occasion, he’s clad in an elegant camo dress suit, and the militancy motif couldn’t be more apropos. LaBruce has spent his entire career dodging vitriol, staring down ideologues at both ends of the political spectrum, sinking heteronormative battleships, and wielding his anti-establishment, anti-assimilationist, anti-you-name-it weaponry to ruffle quite a few reactionary feathers.

Since the mid-1980s when he co-founded seminal queer zine J.D.s out of Toronto, this rabble-rousing Canadian punk has risen through the ranks to be crowned king of the marginals. His campy, super-referential, always X-rated narratives about social misfits looking for tenderness and a little tension relief have remained impervious to pop culture’s passing fancies. The bulk of his oeuvre has been publicly condemned, banned, threatened, or picketed in various cities around the world. And now, he’s being feted by one of the country’s most esteemed arbiters of contemporary art. At the sold-out opening of Bruce LaBruce, Rajendra Roy, MoMA’s chief curator of film, likens him to a Kenneth Anger or Andy Warhol for today’s generation. He also sings the praises of LaBruce’s debut feature No Skin Off My Ass (1991), professing that it changed the course of his life: “I literally would not be standing anywhere close to the film department at the MoMA were it not for Bruce LaBruce.”

High praise for a cinematic loose cannon who never intended to be a serious filmmaker and who was mostly shunned by Canada’s public funding bodies until later in his career. No Skin Off My Ass, a queer retelling of Robert Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park in which LaBruce cast himself as a lonely hairdresser falling for a skinhead, was made on a shoestring ($14,000) budget. The movie’s tag line? “Being a fag is a definite plus.” “It just happened to correspond with the burgeoning gay and lesbian film festival circuit and just sort of became a cult film,” recalls BLaB (the artist’s longstanding acronym). “Suddenly, these sexually explicit scenes that I had shot of myself and my boyfriend, whom I made dress up as a skinhead, were being screened internationally, and that’s how that whole thing started.”

During a very politically charged time in LGBTQ history—with Reagan and Bush, Sr. in power, and the HIV/AIDS pandemic claiming so many lives—LaBruce and his New Queer Cinema peers offered a defiant counterpoint to the status quo, presenting renegade LGBTQ protagonists who shared little with Hollywood’s weakly, two-dimensional queer caricatures. But even within that select crop of edgy moviemakers, LaBruce stood out as the voice of hardcore, tongue-in-cheek dissent with his porn-packed political allegories. By simultaneously titillating and upsetting audiences gay and straight with explicit tales of subversive love, he gained cult acclaim (Kurt Cobain famously declared No Skin to be his favorite film) while scaring away potential industry backers.

Except for porn companies, that is, which gave LaBruce carte blanche to be as bold and badass as he wanted to be. “They gave me great freedom to do whatever I wanted, because they didn’t really care what I did,” he acknowledges. “I don’t think some of my films could ever have been made in any other context.” Among them, The Raspberry Reich, an affectionate satire of the radical left, about a terrorist group coercing others into joining “the homosexual intifada,” and Otto; or, Up with Dead People, a savvy, zombie-porn critique of consumer culture.

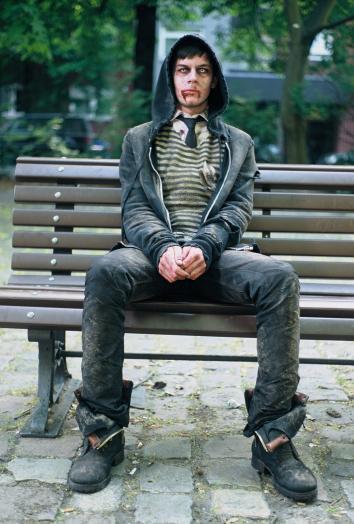

Otto; or, Up With Dead People, 2008. Canada, Germany. Directed by Bruce LaBruce. Courtesy of the filmmaker.

I ask the writer-director whether he’s still fuelled by the same desire to rage against the mainstream machine some thirty years after first putting his indelicate indignation into his zine. “I think my ideals were youthful in a lot of ways and very romantic,” LaBruce tells me. “I felt more naïve about being able to change the world and all these revolutionary principles.” A startling admission coming from the queercore caliph himself. When I press him about the softening of those revolutionary ideals, LaBruce offers his Cuban husband as a case in point: a man who lived through his country’s revolution and harbors a certain disillusionment regarding communism. “He had to pledge allegiance to Che Guevara every day, he lived through homosexual discrimination, and he was starving because of the revolution,” he explains. “I met him when I was touring with The Raspberry Reich, ironically enough, and he was really like, ‘honey, I lived through a fucking revolution, so don’t give me this revolution is my boyfriend bullshit,’” he said, before adding that the hubby teasingly refers to him as Brucito Subversivo.

Listening to LaBruce reflect on his dyed-in-the-wool anti-establishment ethos, it’s clear he would see eye to eye with Raspberry Reich’s militant doyenne, who believes “one man’s terrorist to be another man’s freedom fighter.” But only to a certain extent. “With a lot of extreme radical leftist rhetoric and movements, they get to this point of compromising their ideals,” LaBruce points out. “So I’m very aware of those ambivalences, and as I get older—and it pains me to say this—but … all revolutions are doomed to fail on a certain level.” I scrutinize LaBruce as one would an idealist throwing in the towel, before he adds with a smirk: “That’s when you just have to move on to the next one.”

Which brings us to Gerontophilia, his latest exploration of uncharted desires and the film chosen to launch LaBruce’s retrospective. This one zeroes in on an 18-year-old guy who isn’t gay-identified (classic BLaB), although he recognizes his unusual penchant for sagging male flesh. The film finds him developing an intimate relationship with an elderly man at a nursing home. His first mainstream project, million-dollar picture, and non-sexually explicit feature, Gerontophilia marks a radical departure for this “Advocate for Fagdom,” borne out of a desire not to keep preaching to the choir. “I could make the same kind of film for the rest of my career,” he says, “but I think that’s really boring. I feel like I haven’t strayed too far from those original impulses that made me make my original films.”

I wouldn’t disagree. While the film is more palatable to the average filmgoer than a zombie film featuring a gay porn star screwing cadavers back to life (L.A. Zombie), Gerontophilia’s sweet May-December romance nevertheless challenges viewers to get over their initial shock at the unorthodox coupling. One could even draw parallels between Gerontophilia and BLaB’s zombie movies, for instance, in his critique of an institution overmedicating its elderly until they reach a vegetative state akin to the undead.

LaBruce, who was expecting more blowback around the film from his core fan base, was pleasantly surprised by the response. “What was amazing was showing it at the Palm Springs Film Festival,” he observes. “I had never seen so many men over the age of 65 in one room watching a film of mine. And it’s such an empowering film for them—it’s the grey revolution!”

While some may read Gerontophilia as a mellowing out of BLaB’s most rambunctious, anti-establishment antics, the man appears entirely unfazed. And yet, when I ask him if he still considers making films an act of rebellion—and if that label even matters to him—he confesses to wanting it both ways. “I always think of Barbra Streisand in The Way We Were, when she says: ‘Why can’t we both win?’ And yeah, why can’t I be both: a crazy underground filmmaker and a commercial filmmaker, on my terms? I know that’s very idealistic …”

A tall order, to be sure. But with three gutsy projects in development—including a low-budget sequel to The Raspberry Reich as well as Twincest, “a feature without sexually explicit content” about identical twins separated at birth and reunited 21 years later—it appears as though BLaB will take a valiant stab at that tricky, underground/commercial balancing act. If anyone can pull it off and answer Babs in the affirmative, my money’s on the guy sitting before me, celebratory glass of wine in hand, turning heads with his camouflage garb and big grin. Brucito Subversivo sounds about right.