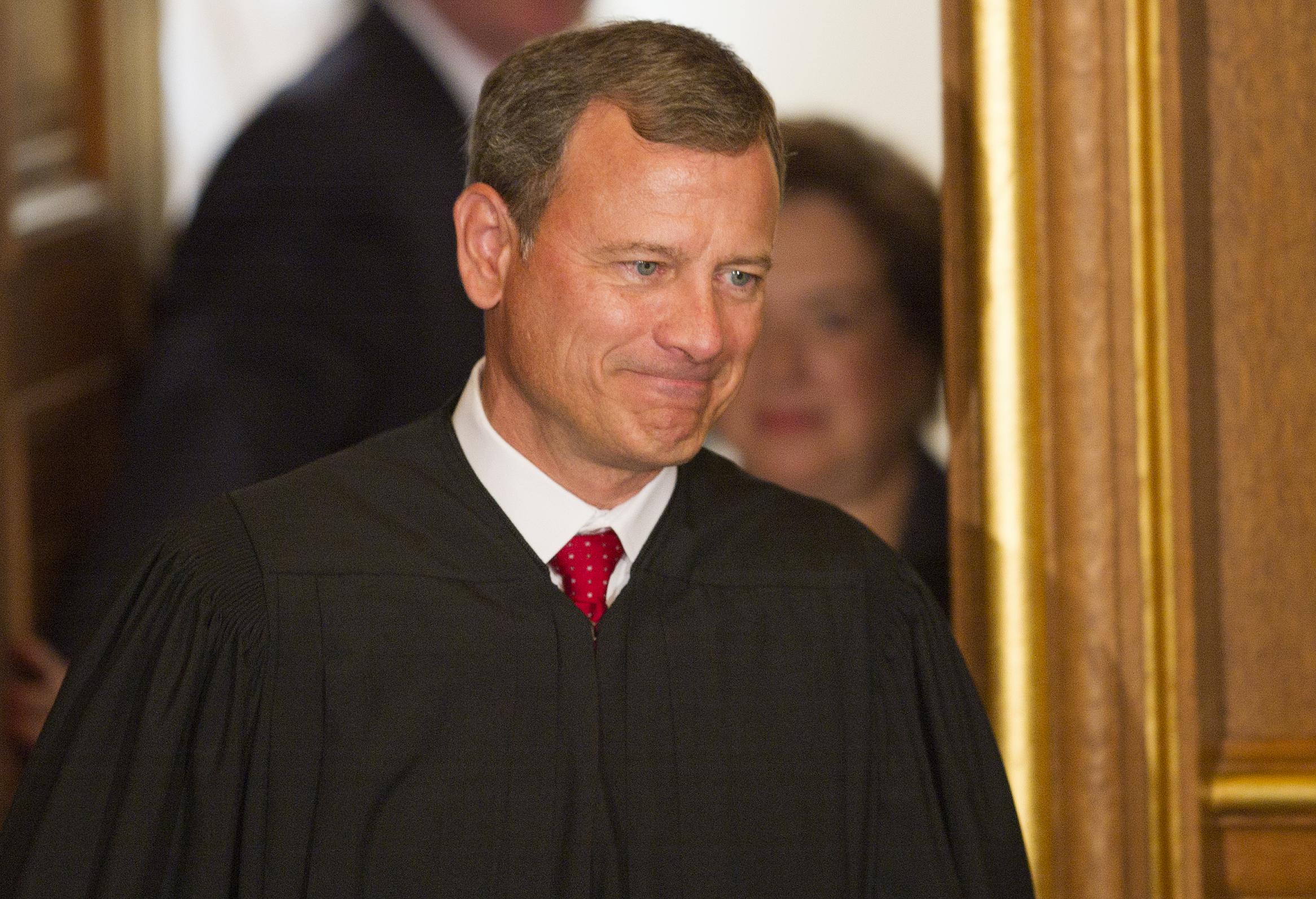

Tuesday’s marriage equality arguments at the Supreme Court confirmed many things: Yes, Justice Anthony Kennedy is still concerned about gay couple’s “dignity”; yes, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is still a fierce defender of constitutional equality; no, Justice Samuel Alito hasn’t stopped spouting nasty nonsense about gay people. But the arguments ended without a clear view into the mind of Chief Justice John Roberts. In recent months, Roberts has been lobbied by the left to support marriage equality—and bullied by the right to oppose it. On top of that, many commentators (myself included) have speculated that Roberts might swing to the side of equality this time around.

On Tuesday, however, the Chief Justice’s views remained opaque. Although he pummeled pro-gay attorneys with tough questions, Roberts also engaged with attorneys representing anti-gay states, treating several of their claims with evident skepticism. At the end of the morning, it appeared Roberts had three options open to him if he decides to cast his vote in favor of equality.

1. Split the baby.

Tuesday’s arguments were divided into two questions: The first asked whether states must perform same-sex marriages; the second asked whether states must recognize same-sex marriages performed out-of-state. Few of the justices seemed interested in the second question—which would only matter if the court first ruled that states need not perform same-sex marriages themselves. But Roberts was animated and inquisitive throughout the hour. In particular, Roberts dwelt on the rarity with which states refused to recognize out-of-state marriages before the rise of same-sex marriage. At one point, he forced Tennessee’s attorney to acknowledge that the last time the state declined to honor an out-of-state marriage was a full 45 years ago.

This line of questioning suggests Roberts has landed on a baby-splitting half-measure. Article IV of the Constitution states that “Full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state.” If Roberts votes against a broad right to marriage equality, he could still write separately and declare that, in his view, the “full faith and credit” clause requires states to recognize valid out-of-state marriages. Technically, this decision would have to do with the Constitution’s guarantees of “liberty” and “equal protection,” but only with dry questions of whether gay marriage falls within the clause’s public policy exception. Thus, Roberts could maintain his position against constitutional marriage equality while avoiding a sharp 5-4 split on both questions presented.

2. Steal the opinion from Kennedy.

This option is a purely tactical one—but Roberts is nothing if not a brilliant tactician. The senior justice in the majority gets to assign who writes the opinion, and the Chief Justice is the most senior of them all. Accordingly, if Roberts cast his vote for marriage equality, he could rip the opinion away from Kennedy and write it narrowly, cabining its logic to the question at hand. Kennedy is infamous for writing gay rights opinions in vague, flowery language that lower court judges can use to expand equality beyond the court’s stated intent. (For instance, the 9th Circuit used Kennedy’s Windsor opinion to assign heightened scrutiny to laws disadvantaging gays—a commendable decision that, alas, has virtually no textual hook.)

In Roberts’ hands, the opinion could instead dole out rights stingily, clearly subjecting anti-gay laws to nothing more than minimal scrutiny and explicitly limiting the opinion to marriage. That way, red states currently considering a variety of viciously anti-gay legislation wouldn’t need to fret that their homophobic measures run afoul of the ruling. At the same time, Roberts would be remembered by a majority of Americans as the justice who heroically secured a constitutional right to marriage for gay people across the country.

3. The sex discrimination option.

Tuesday’s most curious moment occurred when Roberts made this statement:

Counsel, I’m not sure it’s necessary to get into sexual orientation to resolve the case. I mean, if Sue loves Joe and Tom loves Joe, Sue can marry him and Tom can’t. And the difference is based upon their different sex. Why isn’t that a straightforward question of sexual discrimination?

Kennedy asked a similar question in 2013, and the answer then is the same answer today: Same-sex marriage bans are sex discrimination, because they restrict individual’s rights solely on the basis of their sex. Intriguingly, the very first U.S. court ruling in favor of gay marriage cited this rationale, and it recently received some support in the lower courts. But in recent years, most gay rights advocates have downplayed it—mainly because they want to force the Supreme Court to declare that sexual orientation, like sex, is a suspect or quasi-suspect classification that merits heightened scrutiny.

Yet if Roberts decided that gay marriage bans are a form of sex discrimination, he would almost certainly have to rule in favor of equality. Laws that discriminate on the basis of sex, after all, must show “exceedingly persuasive justification” for doing so. Gay marriage opponents can’t even come up with justifications that pass the smirk test. If Roberts used the sex discrimination rationale, then, he could easily invalidate the marriage bans—without subjecting all anti-gay laws to heightened scrutiny. Roberts has slithered his way to an equally complex compromise before. We shouldn’t be surprised if he uses sex discrimination to sneak out of this bind.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of gay marriage at the Supreme Court.