Last year, Charlie Rogers received a message from the administrators of Scruff—a gay dating app that tends to attract hairier, muscular gay men—of which he was a “premium” (i.e. paying) member. The sex app overlords wanted him to remove something from his profile, an element that violated the service’s terms and conditions. Rogers was annoyed, but he complied. He was free to go on using the app—as long as he agreed to lose an incredibly important tool for his business.

Rogers is not an escort. He wasn’t bullying users. He didn’t even have a dick pic for a profile image—the sort of violations you usually hear about. His sin: being a photographer. A photographer, who because he is shy, trawls for subjects for his work on apps like Scruff and, before that, Grindr. For him, it’s a natural use of a digital queer space to access the community, just as he did for years on AOL and Facebook. But from the point of view of the app companies, this use contradicts the terms of service, at the very least in spirit, since it violates the user’s sense that apps are a means of private exchange rather than an open marketplace.

Fine print aside, there are many artists now using gay hookup apps as convenient places to find models and muses, and you can’t really blame them. Artists have always needed human models for their work—even Michelangelo needed a human source for his early versions of David—and a typical Scruff matrix provides plenty of inspiring forms. But when your hunting ground is a community of men who are baring their soul and their six packs in pursuit of affirmation and anal, is it ethical to ask them to come over for art instead of sex?

In the wake of his warning from Scruff, Rogers and I talked about whether any of these ethical questions bother him. He began by pointing out that while he meets a third of his subjects in more traditional ways and approaches another third online directly, the final third contact him unsolicited. And obviously nobody has to say yes. If they do, there are no stipulations about what they have to do during shoots—although the standard practice is to strip down at least to their underwear. “I would be absolutely lying if I said the work doesn’t come from a place of sexual desire,” Rogers told me, grinning over his cup of coffee. “I’d much rather look at a naked person through the lens of a camera if I’d like to have sex with them. It’s why I photograph men and not women.”

This honesty about sexual desire made me wonder if Rogers seeks a certain “type” in his muses. “I tend to go for little muscle guys,” he confessed. “Which is basically because that’s primarily my alpha type.” Rogers’ website could not make this clearer: His beautiful photos—dour in pallet, evangelical in the worship of their subject—are almost entirely of the well-muscled hunk variety. He sometimes photographs people who aren’t this type, he quickly adds, but they just don’t get the same response online as his muscle daddy portraits. Despite the warning from Scruff, he continues to find clients on apps, and he doesn’t regret his methodology at all.

I reached out to both Scruff and Grindr for their official positions on using the apps to find artistic subjects, making it clear that I was referring more to those using the networks to find models rather than paying customers. (Rogers only charges men who approach him for sessions; the cost for those he contacts is simply permission to use them in his portfolio.) While Scruff did not provide comment, Grindr offered the following:

While Grindr supports the arts, utilizing Grindr for any commercial or non-private use goes against our terms of service guidelines.

What exactly “non-private” means is unclear, but based on the terminology in their terms of service, it would suggest Grindr does not want business of a non-romantic or sexual sort—no matter how small—to be conducted on their app.

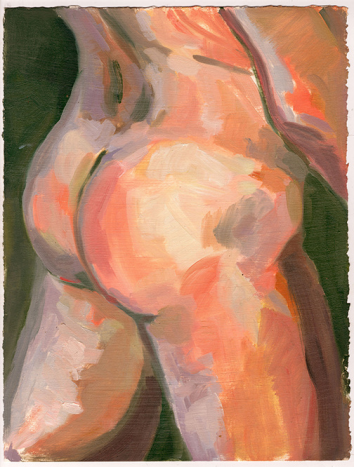

Painting by Ian Faden and Brian Stremick

This wish, however, has not deterred artists Brian Stremick and Ian Faden. Last year they released a book of paintings titled Ass & Dick—no surprises as to the images contained within. The paintings were a side project for the two Pratt graduates who share an apartment in Brooklyn, first started after painting Stremick’s ex-boyfriend. From there, they devised a new series: Painted on gessoed paper and done in quick sittings of 45 minutes or so, models solicited on Grindr and Scruff come in and pose nude between the two artists—one paints the dick, the other the ass. Then they swap and do the opposite.

Stremick’s Grindr account was deleted once before, but he couldn’t say for sure if it was connected to his request for models or the link to the project’s website in his profile. Overall, however, they can’t understand why anyone would have a problem with what they’re doing. “It’s consensual,” said Stremick. “It’s not like anybody forced you to have a profile. And respond. And come over to my house.”

As with Rogers, people the duo asked to come over didn’t pay for the experience. Unlike Rogers, people who volunteered weren’t charged either, meaning that Stremick and Faden were open to anybody near them in the proximity-based apps. Some subjects were not so great, or flaked, or thought it was a convoluted route to a threesome. But overall, the practice allowed the artists to meet a lot of amazing people, such as a married couple who did avant garde nudist plays, or a performance artist who used to crash famous art shows. “It’s been a really good experience for all the models,” Stremick said. “They get to see this little picture of themselves, and it really helps their self-esteem. I run into them on the street after, and when it happens after seeing each other on the app it’s a bit awkward. But now we say ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ ”

Like many queer men (including me), Stremick and Faden are self-confessed addicts of the apps. “For the 12 hours a day I’m awake, I’m on Grindr, and Scruff, eight,” laughed Stremick. For Faden, the strange connection of all these men being on the app together is part of the artistic appeal. “It’s crazy how trusting people are of each other on these apps,” he said. “The fact that people have this thing in common means they feel that they can trust each other.” For the duo, Ass & Dick is a chance to build a real community and a physical network—of paintings and people—out of the miniature, ephemeral gallery on their phone.

The minds behind apps like Scruff are often quick to highlight their capacity to be for things besides sex. In an earlier interview with Outward, Carl Sandler, founder of the Mister and Daddy Hunt apps, praised this expansion: “I think people are using these apps for a lot more than just hooking up, and I think they have the potential to evolve into so much more.” I have to agree. It’s true that allowing apps to become places for miscellaneous tasks—whether it be looking for an apartment or looking for a muse—might be a challenge for the administrators. But Rogers, Stremick, and Faden are not manipulative or cold or trying to cheat the vulnerable out of their hard-earned money. (Which is no surprise: Caring about the human form and caring and human beings usually goes hand in hand.) App makers should treat them and similar users as digital pioneers, not rule-breakers. After all, sex apps revolutionized the way gay people meet up and get off. Why shouldn’t they influence the way we make art as well?