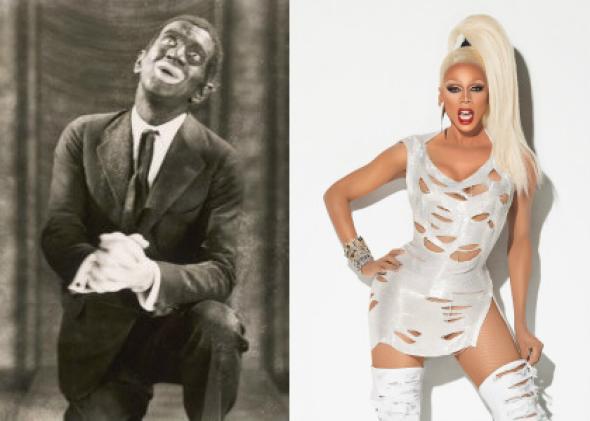

On Jan. 29, Mary Cheney, the openly lesbian and actively Republican daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney, outraged the drag and drag-allied community by comparing drag to blackface in a post on her private Facebook page. Here’s what she wrote about “men who entertain in drag” after seeing a TV commercial for the upcoming season of Logo’s RuPaul’s Drag Race:

Why is it socially acceptable—as a form of entertainment—for men to put on dresses, make up and high heels and act out every offensive stereotype of women (bitchy, catty, dumb, slutty, etc.)—but it is not socially acceptable—as a form of entertainment—for a white person to put on blackface and act out offensive stereotypes of African Americans? Shouldn’t both be OK or neither? Why does society treat these activities differently?

Since the post sashayed off of Cheney’s newsfeed and out into the wider Internet, commentators ranging from college professors to RuPaul herself have been condemning the comparison, mainly defending drag as a means of self-expression and empowerment. As a queen, my initial inclination was to join the backlash. Comparing drag to blackface seemed recklessly hateful, a blunder on par with Republican Rep. Randy Weber’s recent tweet comparing Obama and Hitler. But in the following days, as Cheney’s words ran through my mind, I began to wonder if they held a grain of truth. Beneath her ham-fisted language, Cheney was asking a question all queens and conscientious drag fans must contend with at one point or another: Is drag degrading to women?

For some, the answer to that question is unambiguous. Three years ago, a male co-worker informed me that he would no longer attend my drag shows because his girlfriend thought that drag was “an insult to femininity.” I started to tell him that his girlfriend’s New Balance sneakers were a much graver offense to femininity than my drag could ever be, but the indictment gave me pause—I had no ready defense for the suggestion that my nightlife career was harmful to women. At my shows, women have occasionally made barbed remarks about how sinewy queens create unfair expectations for biologically female bodies. I’ve been told that drag makes a farce of womanhood and that if I really want to understand the experience, I should wear heels all day at the office instead of for a few hours at the club. And last year, when I ran into a madamenoir.com article about the notion that drag queens degrade black femininity, the accusations contained therein were not unfamiliar.

Of course, one could dismiss all of this as the complaining of those who mistake drag’s queer commentary on “femininity” for an exercise in literal gender mimicry or parody—and that is part of the story. But the critics are right to sense a thinly veiled disdain for women among some of my fellow queens. At certain shows, women in the audience are given a particularly bad time. Backstage I have heard complaints that there’s too much “tuna” in the crowd. Making a living by playing with society’s notion of womanhood can even lead to a troubling sort of competitiveness: Watching a female artist perform, I sometimes secretly wonder if a man in a dress could do her job better. Sure, women can be—to recall Mary Cheney’s words—bitchy, catty, dumb, and slutty; but that doesn’t mean they do it well enough to impress me.

That said, just because some drag queens partake in misogyny individually does not make the entire art form inherently misogynistic—and this is where the blackface comparison breaks down. For some perspective on this controversy, I spoke with W. Fitzhugh Brundage, chair of the Department of History at UNC-Chapel Hill, and editor of a fascinating book on black representation in American pop culture, Beyond Blackface.

“My immediate response,” Brundage said, “is that Cheney’s comments show very little understanding of blackface as a historical phenomenon.” One major problem with Cheney’s comparison, he explained, was the yawning gap between the immense cultural influence of blackface at its height and the comparatively low visibility of drag, even in its present RuPaul-sponsored golden age. “In the 1840s, anyone in even a moderate-sized American city had access to minstrelsy, and the rest had access to it through sheet music,” Brundage said. “It was an incredibly pervasive cultural phenomenon. Drag has never enjoyed that cultural weight.” Even if drag were harmful, its impact on American perceptions of women has been so negligible relative to that of blackface that any comparison is foolish. More important, there’s a profound difference in the power dynamics of the two forms of entertainment. “Minstrelsy was being performed by whites in positions of cultural and local power, whereas drag is performed by a marginalized group who are subject to fear and repression,” Brundage said. “To be a drag queen is not an act of privilege. It’s just not comparable.”

While history does not support Cheney’s comparison on the level of fact, the feelings behind her words are not necessarily illegitimate: As a woman, she finds contemporary drag offensive to her sex. In launching our countercritique, the drag community and its allies have ignored these feelings to our detriment.

In the Huffington Post, for example, theater professor and drag queen Domenick Scudera attempts to legitimize drag by pointing to the long history of cross-dressing in theater and other performative traditions. “Men dressing in female garb have been integral to the performing arts for thousands of years in a myriad of cultures,” he writes. “Juliet, Lady Macbeth, Rosalind, Beatrice and so on—all were created by male actors.” I’m not sure if these mainstream theatrical traditions can really be tied to drag, or why their existence should make Cheney or those who hold similar reservations feel more comfortable with drag as it manifests today. In the same publication, Walt Hawkins discounts Cheney’s feelings altogether, insinuating that she’s just confused because she’s having a hard time in her political career: “To be fair, it must be tough to be Mary Cheney,” he writes. “She desperately wants to be a conservative icon and has spent countless hours and dollars pandering to the same political party that wants absolutely nothing to do with her.” The sharpest and most incisive response to Cheney comes from the Advocate’s Matt Baume, who addresses Cheney’s questions in part by pointing to the many women who love drag, even take part in it. He’s certainly right, but that doesn’t change the fact that many do not feel part of the fun.

So what’s to be done? Here’s my proposal: In the same way that many queens listened to the transgender community’s concerns last year over use of controversial terms like tranny within drag culture, we can listen to women this year. Without chilling drag’s wonderful tradition of free expression, we can take this moment to ask if our drag personae and performances truly celebrate feminine gender expressions, or if they lazily mock them. I know that this kind of sensitivity is possible, because some queens are already excelling at it. Just last week, I saw Brooklyn queen Lady Bearica Andrews perform a number in which she literally threw off the marionette strings of domesticity to become an independent woman. It’s rare and risky for a queen to create work that so directly addresses women’s issues, but the audience was on its feet, screaming. Judging from that experience, I don’t think that listening to women’s concerns will hurt us. In fact, I think it may make our drag even richer.