Last year, I wrote an optimistic article for Outward about homophobia in West Africa. Drawing on my own experiences traveling in Senegal as a gay boy and undercover drag queen, I wanted to test American perceptions of the region against the reality. I described how my sexuality was acknowledged and accepted, at least on a personal level, and how diplomatic pressure from President Barack Obama was sparking a new conversation about gay rights in the area. I saw potential for change. There was reason for hope.

Now my optimism has faded. A few weeks ago I went back to Senegal, and the landscape seemed markedly different. Where I once saw a gay community more or less surviving on the margins, I now saw a community that was being pressed completely underground. Its advocates have been silenced, and official scrutiny has become unbearable. And worse, all of this is happening largely out of sight, as other West African crises capture the world’s attention. Gay visibility is at an all-time high in much of the West, but in West Africa, any tenuous gains that may have been achieved are quickly fading.

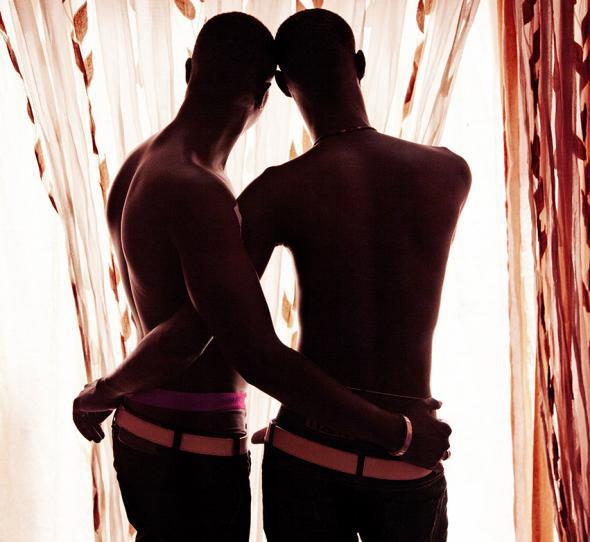

Ernst Coppejans, a Dutch photographer, knows this; he has risked his safety and the safety of his subjects to make queer Africa visible. His award-winning photo-essay Dans Le Milieu features LGBT people in African countries that prohibit homosexual acts. Technicolor-bright, candid, sometimes sensual, Dans le Milieu offers intimate portraits of gay people daring enough to pose for the camera despite the dangers of being outed in their communities. Many of the subjects of his portraits look back at the viewer with a gaze so direct that it reads almost as a challenge. Declaring their existence, they look proud. It was paging through Coppejans’ moving images back in November that called me to return and attempt to document the world I had only glimpsed on that previous trip to Senegal. I had no idea how difficult the project would be, or how soon I would be out of my depth.

* * *

Obstacles emerged before I even left New York. While doing preparatory research, I discovered that coverage of West African gay rights had dwindled in the media during 2014. Googling my heart out in English, French, and Wolof (the language of Senegal), I found only one substantial story about gay people: During the Dak’Art Biennale of Contemporary African Art in June 2014, a nonprofit art center in Senegal’s capital Dakar named Raw Material Company ignored criticism and mounted an exhibition on homosexuality in Africa called “Precarious Imaging: Visibility and Media Surrounding African Queerness.” The center was attacked, its windows and lights broken, and the exhibition was shuttered by the Senegalese government. This did not bode well.

Photo by Ernst Coppejans

Of course, not everything can be found on the Internet; but unfortunately, being on the ground in Senegal didn’t make my search any easier. I couldn’t find a single LGBT person outside my closeted circle of friends. At a cyber café, I scoured gay travel sites, but their advice was shady—go to such-and-such hotel and ask the bell-hop to find a guy who knows a guy, etc. I also found a sort of gay Google Maps with pins marking gay cruising sites worldwide, but the map was essentially bald in Senegal. West African friends back home wrote to offer advice, but nothing helped. And when I researched Groupe Andligeey, a gay rights group that I’d emailed with a few weeks before, I found evidence they’d disbanded. I was left to wander the streets day after day, looking for clues.

On this trip, I found a Senegal—just 10 months after my last trip—in which gay people were hearsay and gay rights were off the table in the media and as well as in private conversations. Obama’s voice blared on local radio stations, but the soundbite—“I am my brother’s keeper”—referred to the Ebola crisis rather than gay rights. And when I tried to talk to my local friends about gay topics, I noticed a profound new coldness.

“The first time you came, it was different,” my friend Moussa said, “Now there are government cameras, and if you do man-to-man, they come to your door and kill you.” I looked out over the crumbling highway near Moussa’s apartment, doubting that the government could have installed such cameras. “There was a boy like that up the road, maybe 25 years old,” Moussa said, seeing my skepticism. “They took him and killed him, and I was happy, because he was not good.” This story made my heart lurch. A gay boy had been killed and Moussa—who once claimed to be gay—was happy about it? “No, not me,” he backpedalled, “But everybody else.” Suddenly feeling threatened, I made some vague pronouncement about the continued existence of gays in Senegal. “Where?” Moussa asked. “Do they hide their faces?”

A good question. Later that day, at a distance, I saw the tell-tale swish of a power-bottom, but in a cinematic turn, he rounded a corner and vanished. And when I departed from Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport some days later, I still hadn’t found what I was looking for. Watching Dakar’s beaches recede from the airplane window, I wondered where I’d gone wrong.

* * *

“After seven months of research, I had a total of two phone numbers,” Coppejans told me.

Discouraged by my lack of contact with anything resembling a gay world, however fragile, during my time away, I had called him as soon as I landed in New York, wanting to hear about his experience as a photographer in West Africa. “I couldn’t find anything, but finally a researcher for Human Rights Watch said ‘Look, you seem really sincere, here are some contacts to get started.’ And the rest of my contacts grew slowly from there.”

Photo by Ernst Coppejans

As Coppejans talked, I realized my problem was simple: I hadn’t been able to find a “gay community” because it simply didn’t exist in any way I could understand it. “There are usually no gay bars, no clubs,” he said. “Gay people stay in contact by SMS and only gather in one another’s homes, if at all.” He described how difficult it had been to find subjects for his portrait series, following leads cautiously and struggling to select locations for shoots—he was afraid to draw attention to his hotel rooms or the homes of his subjects. (The stressful secrecy he described was echoed in interviews I later conducted with gay Senegalese expats here in New York.) Ultimately, the sense of danger was so wearing that he cut his project short and flew home. What would happen, he wondered, if his camera’s memory card fell into the wrong hands?

The images that Coppejans bravely brought back are invaluable not simply because they are beautiful, but because they document and make visible a world that would—must—otherwise remain hidden. They give living, human faces to a community that we usually hear about only in the context of death, violence, and suppression. But for Coppejans, the pictures seem to be a source of strain rather than triumph. Even as he receives accolades for the series, he is plagued by worry for its subjects, and a certainty that their situation is permanent. “There’s no light at the end of the tunnel for them,” he says. “The laws and the mentality of the people around them are not changing.”

Having attempted to follow in his footsteps, I understand how Coppejans feels. I saw a number of things in Senegal that won’t fade from memory: a boy crushed by a truck in front of me; United Nations tanks strolling toward a failed coup in The Gambia; the look that flashed across a friend’s face when a drag queen’s business card fell out of my wallet. But it’s what I didn’t see that truly disturbed me: no gay gatherings, no gay kisses, no gay smiles. And I think constantly about the boy Moussa mentioned. He was only a little younger than me—would we have been friends if we met? Would he have helped me to write this article? Was he even really gay, or just falsely accused? I don’t know. But I often wake from dreams where I see him. Or nightmares where I am him.

Editor’s note: Some names in this essay have been changed in the interest of safety.