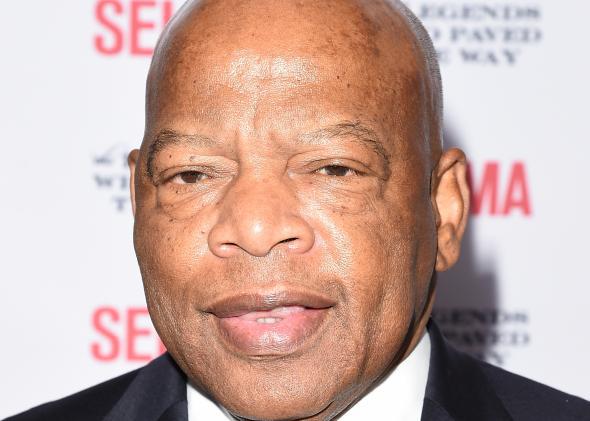

“It cannot wait,” says the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil rights movie Selma, which opened nationwide last Friday. King is pleading with President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the Voting Rights Act. It’s a trenchant scene whose message is not lost on Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., who is also depicted in the film. Lewis, now 75, is still an idealistic agitator whose sense of urgency for dismantling discrimination has long extended to gay rights.

Asked how LGBTQ advocates should strive for policy change—incrementally and gingerly, or with requests for wholesale overhaul whatever the political cost—Lewis is unequivocal: “If something is just, you don’t put it off. You always demand the here and now and continue to push,” he told me by telephone last week.

Lewis, the sole survivor of the so-called “Big Six” leaders of the civil rights movement, recalls the events leading up to the keynote speech he gave at the historic March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Some believed the movement was moving too quickly. “Someone said, ‘We must wait.’ And I said, ‘We don’t want our freedom gradually—we want it now,’ ” recalled Lewis, adding, “That must be the demand of any movement.”

Lewis knows well the sometimes perilous cost of speaking truth to power. He was viciously beaten by state troopers and sustained a skull fracture on “Bloody Sunday,”—the day in 1965 when black residents of Selma, Alabama, attempted to peaceably march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to demand equality in voting rights in the segregated South, an event that is captured in Selma.* “I really felt that I saw death at that moment,” Lewis wrote in his 1998 memoir, Walking With the Wind.

He says those formative experiences as an activist informed his dedication to protecting all human rights. In particular, he says, it inspired his fiery speech on the House floor against the Defense of Marriage Act—which he deemed “hate legislation”—before it passed in 1996.

That day, Lewis said he had the same feeling in the pit of his stomach as when civil rights activists opted against choosing Bayard Rustin, a key architect and organizer of the 1963 March on Washington and a close adviser of King’s, to be chairman of the march. Rustin was gay and considered a liability because he had been arrested a decade earlier on morals charges.

“He was pushed aside. He was brilliant, but they thought it would hurt the movement—that certain senators would use it against the march. It was wrong,” Lewis remembers. “It was an affront to the man, to what he stood for, and to the contributions he made.”

Lewis, a congressman since 1986, was an early co-sponsor of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, known as ENDA, a job-protection bill for LGBTQ people that has been introduced into Congress for four decades; the most recent version died in committee late last year. He says his support of such legislation is born out of the basic contention that “you cannot talk about breaking down barriers between races or the right to vote without having equality for everybody, including based on gender and sexual orientation.”

He agrees that various incarnations of ENDA have been imperfect, as for example, in 2007, when it lacked language to protect transgender people and, most recently, when it contained exemptions for religious institutions. Lewis has a simple directive for how to pass such important legislation in its most inclusive form: “If we are going to continue to make progress, whether it is for marriage equality or discrimination against members of the gay community in the workplace, you have to continue to be physical, continue to speak up and speak out. To find a way to do what I call ‘making some noise, getting in the way,’ and educating people and sensitizing them.”

Such efforts might be directed at would-be presidential candidate Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., who last Wednesday, on the heels of same-sex marriage becoming legal in his home state, said he does not believe there is a constitutional right to such unions. Lewis said that contention violates the spirit of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law.

Lewis concedes that the American public has a distance to go before arriving at what he often refers to as “the beloved community, where we respect the dignity and worth of every human being. As a nation and a people, we must get there. But we will get there,” he says.

*Correction, Jan. 13, 2015: This post originally misstated the year that “Bloody Sunday” occured. It was 1965, not 1963.