Earlier this month, Leslie Feinberg, a well-known transgender advocate and author of Stone Butch Blues, died at the age of 65. Feinberg’s last words, “Remember me as a revolutionary communist,” contain the echo of a time that seems long past, when the only people who ascribed any importance at all to LGBTQ issues, apart from queers themselves, were far-left radicals, and when the oppression LGBTQ people and other minorities faced was firmly linked to class struggle and the exploitation of working people by the rich.

As a sociology major at a liberal university in the late ’90s, I learned to look for the exploitation of workers and the growing influence of corporate interests throughout America’s cultural, political, and economic systems. I was taught that the clothing I wore was sewn by sweatshop workers, the food I ate was harvested by migrant laborers, and the decline of unions and the rise of free trade agreements would lead to increasing inequality and the destruction of the American dream. Then I got out into the real world and learned that nobody really cared much about any of that. What people on the left and right did care about was whether the law ought to allow lesbians and gay men to marry. While there have been other issues queer people advocated for, marriage equality was the one that captured imaginations and won or lost elections. The struggle of lesbians and gays for marriage equality was, by then, already far removed from the struggles of other segments of society. But it was not always so.

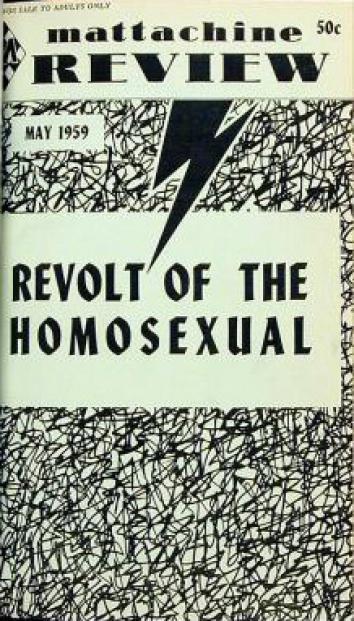

The grandfather of the LGBTQ movement in America, the founder of the very first gay rights group, was a communist in the 1930s, back when Marx’s critique of capitalism was an exciting new idea rather than a tired old one. Before founding the Mattachine Society in 1950, Harry Hay was active in left-wing art and theater and served as a Communist Party functionary, overseeing union activity among theater groups in New York City. Later, his ties to Marxism were exposed and used to clip the wings of the Mattachine Society after a couple of early victories brought the group to the attention of conservative, vehemently anti-Communist ‘50s society.

As it began, so gay activism continued. When the Stonewall riots reignited the movement approximately two decades later, the first group to form in its wake was the Gay Liberation Front, which immediately adopted an anti-capitalist, anti-racist, feminist, pacifist platform in addition to its gay rights mission. Steeped in ’60s radicalism, its leaders (one of whom was Hay) viewed the evils of militarism, sexism, racism, and homophobia as one and the same—symptoms of a capitalist system that brutalized the many for the benefit of the few.

But Marx’s star was fading. American capitalism, as moderated by unionization and progressive political reforms, improved standards of living across the classes and led to innovations in science and technology that made our country prosperous and safe. The revolution failed to materialize, and nations that claimed the communist mantle fell laughably short of the imagined, utopian ideal. Postmodernism arose to take Marxism’s place, rejecting the idea of simplistic overarching explanations for all societal ills. The struggles of each minority group came to be seen by progressives as separate and distinct, the left fragmented, and advocacy on behalf of gays and lesbians became just one of many distantly connected strains. Newer groups, like the Human Rights Campaign (formed in the ’80s as a political action committee dedicated to funding pro-gay congressional candidates), replaced old-fashioned revolutionary fervor with mainstream Democratic Party politics and a middle-class worldview that dominates the movement to this day.

Today, the most familiar face of LGBTQ rights is middle class and consumerist. This has almost certainly been to the movement’s benefit—it seems unlikely to me that the acceptance of gays and lesbians could have advanced as quickly or as far if it had remained tied to ideals like pacifism, unionization, or anti-poverty. Free from such unpopular fetters, the LGBTQ movement’s push for same-sex marriage stands as the only significant victory the left can claim in my lifetime. Meanwhile, wages have stagnated, inequality has risen, pointless wars have been fought and lost, and reproductive rights have been eroded. Without Marxist economic ideas to stitch the left together, it largely fell apart. But as capitalism’s excesses grow and issues like inequality come into fashion once again, it remains to be seen whether an alternative to older ideas like solidarity or class struggle can be found that will reanimate the connections between the severed limbs of the left—and if the victorious LGBTQ movement will have more support to offer other progressive causes once same-sex marriage becomes the law of the land.

See also: “Stone Butch Blues Isn’t Just for Queers”