The warrior-poets were among the most significant chroniclers of World War I. “If I should die, think only this of me;/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is forever England” and “In Flanders fields the poppies blow/ Between the crosses, row on row” are lines that live on in the popular imagination, 100 years after the outbreak of hostilities.

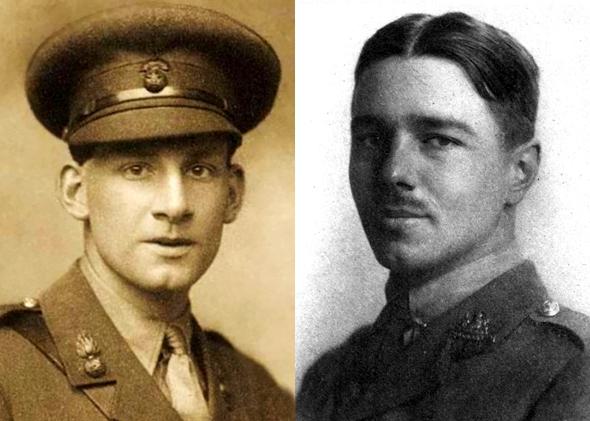

But many of the finest poems of the Great War—including “Anthem for Doomed Youth” and “Dulce et Decorum Est”—might not exist were it not for the pivotal bond between two gay men who were the era’s finest war poets: Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

Sassoon, the older of the pair, enlisted in August 1914. He served on the Western Front with the poet Robert Graves and “gentle soldier” David Cuthbert Thomas, with whom he had a relationship while Sassoon was studying at Clare College, Cambridge. In March 1916, Thomas was shot through the throat and died. Sassoon wrote two poems in his memory, “A Letter Home” and “The Last Meeting,” the latter of which speaks of the affection Sassoon evidently felt for Thomas:

I called him, once; then listened: nothing moved:

Only my thumping heart beat out the time.

Whispering his name, I groped from room to room.

Quite empty was that house; it could not hold

His human ghost, remembered in the love

That strove in vain to be companioned still.

It wasn’t until autumn 1917 that Sassoon would meet Owen. After writing “Finished With the War: A Soldier’s Declaration,” which stated that he could “no longer be a party” to a war that he believed to be “evil and unjust,” Sassoon was deemed unfit for service and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, Scotland. Owen was also at Craiglockhart, having been diagnosed as suffering from shell shock. There, under the care of the pioneering psychologist W.H.R. Rivers, Owen was editing the hospital’s literary journal, The Hydra, as part of his occupational therapy.

Their first meeting is captured in Pat Barker’s historical novel Regeneration. Owen, short and dark-haired, entered Sassoon’s hospital room armed with five copies of his book. Stammering—a consequence of shell shock—Owen asked Sassoon to sign them. In Barker’s account, the two men discussed the war and Sassoon’s poetry, and Owen asked Sassoon to write for The Hydra. “Everything about Sassoon intimidated him,” Barker writes of Owen. “His status as a published poet, his height, his good looks, his crisp aristocratic voice. … Above all, his reputation for courage.”

Owen was in awe of Sassoon, and their relationship at Craiglockhart would prove to be essential to his poetry. Before meeting Sassoon, Owen was a slave to Keats and Shelley, mimicking their Romantic style. He was also largely unpublished. Sassoon, mentoring Owen during the time they had together, encouraged him to write more realistically and directly, using a less elaborate, more colloquial style.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” is a product of Owen’s bond with Sassoon, and not just in terms of tone. Sassoon aided Owen in revising it, suggesting words, correcting conjunctions, even suggesting the title, recommending a change from “Anthem for Bad Youth.” Sassoon’s handwritten edits can be seen on the final draft, providing the finishing touches to lines such as “No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells” and “Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds.”

Sassoon also helped Owen work on “Dulce et Decorum Est,” which is often recalled for the final two lines, “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/ Pro patria mori”—it is sweet and fitting to die for your country. The poem might be the clearest indication of Sassoon’s influence on Owen, vividly and frankly capturing the horrors of trench life and mechanized, chemical warfare:

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

There’s no way of knowing if Sassoon and Owen had a sexual relationship at Craiglockhart, but Owen’s later letters to Sassoon are full of love. Writing on Nov. 5, 1917, after he had been discharged from hospital and was returning to duty, Owen tells Sassoon, “Know that since mid-September, when you still regarded me as a tiresome little knocker on your door, I held you as Keats + Christ + Elijah + my Colonel + my father-confessor + Amenophis IV in profile.”

Owen continues:

In effect it is this: that I love you, dispassionately, so much, so very much, dear Fellow, that the blasting little smile you wear on reading this can’t hurt me in the least. … “You have fixed my Life—however short. You did not light me: I was always a mad comet; but you have fixed me. I spun round you a satellite for a month, but I shall swing out soon, a dark star in the orbit where you will blaze.

Owen died on Nov. 4, 1918—one week before war’s end—crossing the Sambre-Oise Canal in the face of German machine gunfire. “His own life is a perfect example of the loss of illusions and innocence that the war brought to our entire civilization,” British broadcaster and historian Jeremy Paxman has written, deeming him “the greatest of all the war poets” and “the voice of a generation”.

Sassoon, who survived the war and died in 1967, would later write, “W’s death was an unhealed wound, & the ache of it has been with me ever since. I wanted him back—not his poems.”