The opening titles of Transparent, the critically acclaimed series currently streaming on Amazon Prime, are culled mostly from video clips of bar and bat mitzvah videos from the 1960s to the ’90s—ending with the time code “JAN. 1 1994.” It’s a nostalgic montage that alludes to a crucial turning point in the show’s narrative: the year that Mort Pfefferman, played by Jeffrey Tambor, begins to come out as Maura—a transgender woman.

But a moment before the main show title comes up, the montage of party shots cuts momentarily, almost seamlessly, to a figure in a shimmering blue dress. This is a clip from Frank Simon’s 1968 film The Queen, a rarely seen and ground-breaking documentary of the 1967 New York Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant. The film is one of the earliest screen portrayals of the lives of “female impersonators”—some identifying as gay men, some beginning to identify as trans women.

Taken together, the clips could be the introduction to a gender studies course: What does it mean for the bar mitzvah boy to “become a man,” and the drag queen to “become a woman”? As Maura explains in the second episode while coming out to her eldest daughter, she has not begun to dress as a woman: “All my life, my whole life, I’ve been dressing up like a man.” But the use of The Queen in Transparent’s opening also hints at the ways trans identities and communities have evolved, both in the decades since the documentary’s release and over the years of Maura’s life—clearly, these titles are doing more work than it might first appear.

Photo credit: Beth Dubber

The Queen was first screened at Cannes in 1968 and soon after opened in movie theaters in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston, among other cities. Filmed over five days with five cameras, the documentary is largely narrated by emcee and pageant organizer Flawless Sabrina—listed in the credits as Jack Doroshow—who has brought together contestants from around the country: Miss Boston, Miss Chicago, Miss Brooklyn, Miss Fire Island. The film depicts the contestants as they rehearse for stage numbers, prepare their outfits and wigs, and finally as they compete before a full auditorium. Flawless Sabrina, in the persona of what she calls “bar mitzvah mother … you know, gaudy gowns and pushy,” coaches and directs. “Five points for walk, five points for talk, five for bathing suit, five for gown, five for makeup and hairdo, and 10 for beauty.” The film is, in many ways, a predecessor of Paris Is Burning, Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary of the Harlem drag ball community. (One of the Queen contestants glimpsed in Transparent’s opening is Crystal LaBeija, a commanding performer who would go on to found one of New York’s more legendary ball houses.)

The making of The Queen was spearheaded by Flawless Sabrina herself. Speaking with me recently over the phone, she described first arriving in New York in 1957, just out of college. She took a room at the Sloane House YMCA near Penn Station, and soon discovered “some kids” getting dressed down the hall in preparation for a drag ball at the Manhattan Center. Soon after, she began organizing pageants of her own, and by the mid-1960s, began raising money to make the film. The goal was to capture a world she felt was quickly “evaporating.” “We had been a totally sub-rosa, clandestine situation, and now we were becoming more illuminated,” she said. “It had become a social curiosity for some rich kids that were slumming, sort of a look at the underbelly.” Andy Warhol eventually led an effort to raise money for the film, and his clout helped bring in a starry list of judges including columnist Liz Smith, artist Larry Rivers, Grove Press editor Barney Rossett, and writers Terry Southern and Rona Jaffe. Timothy Leary showed up in drag, and Warhol superstar Mario Montez gave a performance of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.”

But the most revealing and intimate moments of the film are in the hotel where the contestants stay in the days leading up to the pageant. Diverse in race and age, they perform for one another, prepare each other’s makeup, and share stories about their families, their lovers, and their lives outside the “drag bag.” One contestant recalled going before the draft board: “He asked me about boys, and I said, you know, I like boys, so he said, ‘Next!’ ” Another was told, “You really should have been a girl, it’s too much, we can’t use you.”

Their stories reveal the extent to which understandings of gender identity and sexuality were in flux. Only a year before The Queen was made, Johns Hopkins Hospital opened the Gender Identity Clinic, the first university medical program to offer hormone treatments and sex reassignment surgeries. It was big news, with headlines in Time and Newsweek and on the front page of the New York Times. As scholar Susan Stryker puts it in her book Transgender History, the opening of the clinic, along with the founding of similar research and treatment programs across the country, inaugurated “what could be called ‘The Big Science’ period of transgender history.”

But expanding medical interventions also led many people to make sharper distinctions between gay and trans identities. One of the contestants in The Queen explains, “I have enough money to go through the sex change, and I live only 30 miles from Johns Hopkins, but it’s the last thing I would want. I know that I’m a drag queen, I’ve been a drag queen for a long time, I’ve been gay for a long time. But I certainly do not want to become a girl, even if I could have a baby.”

Harlow—the eventual winner of the pageant—would, on the other hand, go on to have sex reassignment surgery a few years later. Now known as Rachel Harlow, she opened several successful nightclubs in Philadelphia and nearly married Grace Kelly’s brother John Kelly, Jr.—a city councilman and Olympic gold medalist. As Flawless Sabrina recalled, “Harlow’s feeling about the drag thing was that that was another lifetime. After Harlow got the change, she became a woman, and even though she was quite well known in the capacity of having been trans, she really still set that aside and she became very much a woman—as she is today.”

Such efforts to stake out the boundaries between identity groups were typical of the time. As historian Joanne Meyerowitz shows in her book How Sex Changed, self-identified gay men and lesbians as well as “transvestites” and “transsexuals” (the most commonly used terms of the time) frequently defined themselves in contrast to, and sometimes at the expense, of each other—working out the distinctions between sex, gender, and sexual desire.

Relationship, #23 (The Longest Day of the Year), 2008-2013. Courtesy of Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

The idea to include The Queen in the Transparent opening titles came from associate producers Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst. Drucker and Ernst have steadily won acclaim for their art work over the last three years, with projects featured in the inaugural Made in L.A. 2012 biennial and the 2014 Whitney Biennial. They came onto the show as consultants early on, after Ernst met creator Jill Soloway at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, and have since been involved in nearly every aspect of the show’s production, from casting to writing. Working with titles designer Jean-Paul Leonard and Soloway, they developed the concept of using found footage for the opening credits. They found the bar and bat mitzvah footage online or through friends. (The young boy voguing had been a YouTube sensation; he was also, it turned out, Soloway’s cousin.) But for early footage of transgender life, they quickly turned to The Queen.

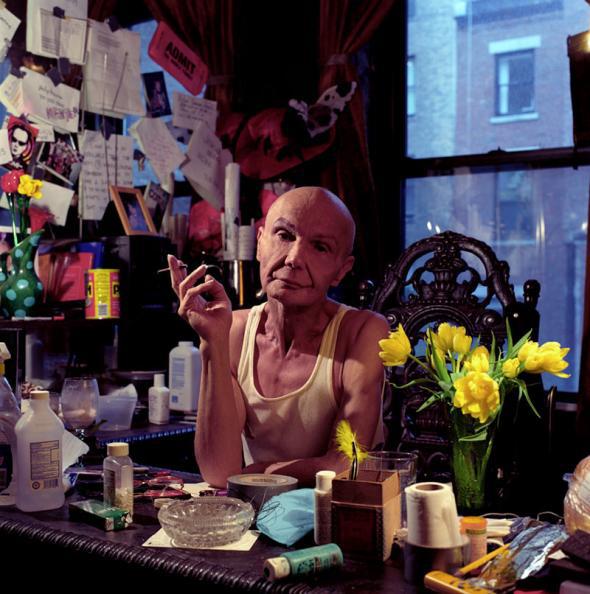

Drucker has a long history with both The Queen and Flawless Sabrina. As a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York, Drucker learned about the film in 2003 from a queer underground zine called My Comrade and ran out to find it. As Drucker told me, “When I first saw The Queen, it was in pursuit of a history I felt a part of. I was at such an early stage in my understanding of my own gender. I was always interested in cult films, foreign films, independent films—the more obscure the better. And I think anything I could find connected to trans people or drags queens was a validation of my own difference—just knowing the path was paved a long time ago, it wasn’t going to start with me.” Soon after, Drucker was by chance invited to an art show being hosted at Flawless Sabrina’s apartment.

The two had met once before—at Wigstock, an annual drag festival—but the opening turned out to be the beginning of a decadelong kinship (Flawless Sabrina calls Drucker her “grandchild”). They have also collaborated on several projects, from Drucker’s MFA thesis to She Gone Rogue, a 22-minute film written and produced by Drucker and Ernst and featuring Flawless Mother Sabrina alongside another legendary trans performer, Holly Woodlawn, and genderqueer performer Vaginal Davis.

Zackary Drucker, Excerpts from “5 East 73rd street” 2005 - 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Drucker and Ernst aren’t the only ones on the show with transgender history on their minds. Early in producing the first season, the writing staff visited the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California and looked at all their transgender periodicals, from Transvestia, a magazine for straight-identified cross-dressers founded in 1960, to TV-TS Tapestry, founded in 1980, to Chrysalis, a transfeminist quarterly. They also made photocopies of issues, and hung them around the writers’ room.

This longer history traces shifts between community and exclusion as identity categories were tightened and loosened. As Ernst told me, “We did a lot of research about the separateness and also intersections between the trans and the cross-dressing world.” In a flashback episode, Maura goes to Camp Camellia, a weekend retreat for cross-dressers. But when Maura learns that one camp-goer was exiled for taking hormones, she begins to suspect she may not fit in as well as she hoped. Maura’s world in 2014 seems more intentionally inclusive: She goes to the local LGBT center for support groups and yoga classes (“Namaste, hey, girl, hey”), and performs in a trans talent show—though there are moments of alienation there, as well. Transparent, for all its characters, seems ultimately to track the pleasures and difficulties of seeking empathy, connection, and affirmation.

There is also a longing for connection and recognition in The Queen—for five days, its participants demonstrate remarkable kindness and care for their differences, a sense of what Drucker calls their “unity.” “There weren’t all the distinctions that there are today,” she observes. Ernst, too, reflects: “Maybe some of them are trans, and maybe some of them are drag queens, it’s really kind of loosey-goosey. There’s not really this identity politics that makes these identities distinct.” Today, the terms, meanings, and boundaries of trans identity continue to shift, often contentiously, reflecting histories of marginalization and creative resilience. As Ernst puts it, “Trans history is being written right now. It’s all in the middle of an evolution.”

The final cut of the opening montage was eventually edited together by Ernst—including some footage from the Camp Camellia scenes. (Ernst can be seen on the dance floor, as a cross-dresser, with an old VHS camera.) Still, The Queen stands out among the other clips—the music swelling just as the scene from the documentary comes into focus. The lineage from Transparent back to The Queen was not obvious, but the link is an important one to make visible. As Drucker says, “Our history is so unrecognized and unwritten, it’s an incredible document.”