The Illinois Family Institute has long been listed as a “hate group” by the Southern Poverty Law Center, so news that their “cultural analyst” Laurie Higgins has said something incendiary about LGBTQ people is not a surprise. This time, however, the particular focus of her anti-gay rant is worth considering, if only because it partakes in the phenomenon of absurd conservative rhetoric sort of sounding good if you don’t think about it too hard.

Higgins’ ire is currently directed at the American Library Association’s “Banned Books Week,” an annual event meant to draw attention to issues of intellectual freedom and censorship, particularly in the realm of which “challenged” books are or are not available in public libraries. Higgins accuses librarians of “ridiculing parents who, for example, don’t want their six-year-olds seeing books about children or anthropomorphized animals being raised by parents in homoerotic relationships,” adding that “responsible patrons are asking that books that deal with highly controversial topics, particularly sexual perversion, be removed from the section of the library in which children are encouraged by parents and librarians to roam and read freely.” She then argues that librarians themselves are the ones responsible for book-banning, since books that “challenge Leftist assumptions about the nature and morality of homosexuality” are not, in her view, often enough included on library shelves.

Though it is deeply flawed (more on that in a moment), this argument has at least the veneer of plausibility. If we are invested in the virtue of intellectual freedom in libraries, why shouldn’t all voices be included? But the truly hateful origins of Higgins’ argument become clear in her crass proposals for the sort of books she’d like to see more of in the children’s section:

- “[Y]oung adult (YA) novels about teens who feel sadness and resentment about being intentionally deprived of a mother or father and who seek to find their missing biological parents.”

- “[D]ark, angsty novels about teens who are damaged by the promiscuity of their ‘gay’ ‘fathers’ who hold sexual monogamy in disdain.”

- “[N]ovels about young adults who are consumed by a sense of loss and bitterness that their politically correct and foolish parents allowed them during the entirety of their childhood to cross-dress, change their names, and take medication to prevent puberty, thus deforming their bodies.”

- “[N]ovels about teens who suffer because of the harrowing fights and serial ‘marriages’ of their lesbian mothers.”

- “[P]icture books that show the joy a little birdie experiences when after the West Nile virus deaths of her two daddies, she’s finally adopted by a daddy and mommy?”

The fairly monstrous HIV/AIDS jab embedded in this last “suggestion” makes my skin crawl, but then I’m sure that’s the point—so well done, Laurie.

But the author’s argument for including actively anti-LGBTQ books alongside inclusive selections in the library remains to be considered. Let’s begin by addressing the question of whether such books are being excluded from libraries: According to a quick search of the New York Public Library’s collections, they aren’t, at least not in a supposedly liberal city like New York. The majority of the specific titles Higgins lists are currently available, so read them all, if you like.

Higgins’ real fear, though, seems to be that children might stumble upon a book—like this illustrated one about a same-sex penguin couple—that presents LGBTQ people and families as a positive (or at least normal) part of human life, and thus come to the “wrong” conclusions about those people. Her argument is that fairness demands that such representations must be directly countered by, I don’t know, books in which gay teenage foxes are kicked out of their dens to starve on the street. Anti-gay attitudes need more visibility, Higgins believes.

Of course, this demand—a manifestation of the absurd conservative persecution complex—ignores the fact that much of the library is already anti-gay, if only in the sense that most of the books published in human history completely ignore the existence of LGBTQ people; and if they do acknowledge us, they do so in a wholly negative light. To include a few mild pro-gay or gay-acknowledging books in the children’s collection or elsewhere hardly shifts the ideological heft of most libraries toward some sort of liberal utopia. To the contrary, it simply begins to serve and represent members of the reading community who until very recently were forced to be invisible. This, it seems obvious, should be one of the librarian’s primary goals.

But making queer people visible through books—whether to children or adults—is a very dangerous proposition for people like Higgins. Because just knowing that LGBTQ people really exist is already a step toward treating us humanely, and simply realizing that some author somewhere respected themselves or their friends enough to represent us positively already begins to challenge the prejudice that a reader might be hearing beyond the library doors. If you aren’t terribly fond of the way human empathy tends to work, books truly are frightening objects.

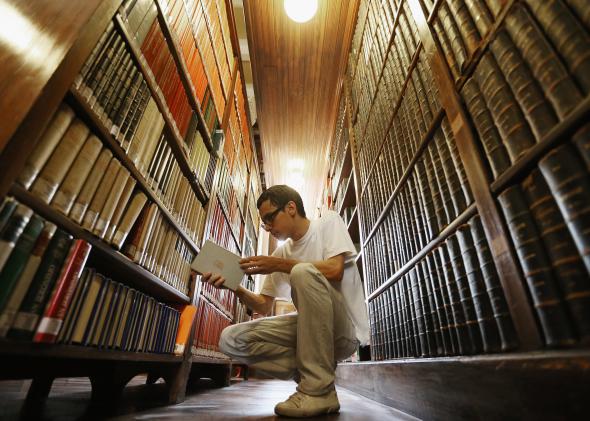

In any case, the point here is that libraries—even children’s sections—aren’t, can’t, and really shouldn’t be ideologically neutral grounds. This is what Higgins would have you believe is her modest, “common sense” goal; but again, the absence of LGBTQ-affirming books would be, in itself, an ideological choice at this point. No, libraries cannot be neutral, but we should strive to be sure that they are as capacious as possible. I’d argue that there are enough shelves stuffed with the kind of pages Higgins likes already—we could probably stand to have a few more dedicated to queer-friendly spines going forward.