When RuPaul’s Drag Race sparked controversy around words like “tranny” and “shemale” in gay—and especially drag—circles back in March, the conversation was largely about who’s authorized to use those expressions, which can be seen as slurs. But another question emerged from the furor that was less predictable, if equally contentious: What, exactly, is a drag queen? Is she a full-fledged resident of the “trans spectrum” or a man who wears a dress for tips? From Facebook posts to splashy feature stories, queens have been arguing that they are more than divas, dolls, or clowns. But what does that “more” really mean?

As a working queen still trying to figure all this out myself, I wanted to explore the issue further. So last weekend I tossed a notepad in my sequined purse and set off to ask a gaggle of New York City gurls what they wanted the world to know about drag as an identity.

The first thing that the ladies agreed on was this: There’s more to drag than looking fierce. From Broadway’s Pageant to Logo’s Drag Race, drag performers are often presented in the context of literal or figurative beauty contests, when in fact, beauty is really a small part of the drag experience—and only for certain kinds of queens at that. Among the ladies I interviewed, even Roxy Brooks, one of New York’s top glamour queens, downplayed the role of looks. “Sure, drag is hair and makeup,” she said, “but it’s also acting, dance, production, and every other craft I’ve learned since I started theater at age eight. Drag is an all-inclusive art.”

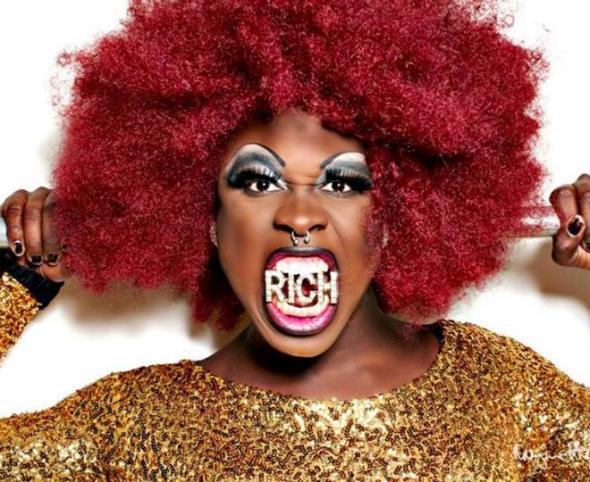

Photo credit: Preston Burford.

I cast an eye over Roxy’s elaborate dress, which looked like something from a Baz Luhrmann vision of the Ziegfeld Follies. She must have sold her soul for that fancy getup, and here she was talking to me about drag as a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk. (Werk, indeed.) As a pageant queen, I asked, didn’t she think that looks came first? “I don’t like labels like pageant queen,” Roxy said. “Anyway, even pageants aren’t all about perfecting your looks. They’re about perfecting what you’re good at. And some queens make an art of looking busted.”

Roxy was referring to the wonderful world of messy queens—those careless disasters who are relatively unknown to mainstream culture despite their essential role in the dragosphere. I’m not talking about “creepy” queens like Sharon Needles, who artfully flirt with horror, or queens like Gia Gunn, who … nevermind. I’m talking about queens for whom beauty is a joke, queens like Ari Kiki.

“I could do pretty, I could do a look,” Ari told me. “But I grew up with Laurel and Hardy, Tom and Jerry, and The Three Stooges, and that’s what I wanted to bring to drag: humor.” She has succeeded. Known for her hot-pink lopsided smile and chest hair, Ari’s reckless pratfalls break railings, chairs, and ankles, all for the sake of a brand that has nothing to do with looks. But true “I woke up like this” queens like Ari remain less visible to the general public because they can’t be re-packaged for mainstream consumption. Their style depends too much on their thrilling, threatening physical presence, which doesn’t translate to television. More importantly, they don’t look like America expects queens to look. “Ari came out of my work with the New York City Anti-Violence Project where I learned about the gender issues that most gay boys don’t bother to learn about,” Ari said. “That’s where Ari began to form in my head as a genderfuck character.”

Which brings us to the next thing the gurls wanted everyone to know about drag: It’s not just about looking like a lady. Since Conchita Wurst made headlines with her bearded-Penelope-Cruz looks on Eurovision in May, more people are aware that “serving fish” (achieving a female illusion) is not drag’s Holy Grail. But the misconception persists that a queen’s sole aspiration is to look like a woman. I talked with the lovely Flippe Kikee about this expectation, because she presents such a strong female illusion that her audience members sometimes crassly place bets about her gender. When we met, she was out of drag and sporting five o’clock shadow.

“Don’t get me wrong, after two hours of painting my face, I don’t want to be called ‘sir’ by a cab driver,” Flippe told me. “But for me, it’s less about making people see me as a female and more about developing and losing myself in a character. It’s the ultimate method acting.” As she talked, I thought about my own experience with drag, and my need to construct a female body where I could feel comfortable. Didn’t Flippe ever have the same feeling? “It’s more that I’m drawn to androgyny,” Flippe said, gesturing to her contradictory beard and blouse. “I love walking the line. As a boy, I’m just this side of feminine. When I become Flippe, I flip over to the other side.”

For some queens, creating a female illusion takes a back seat to delivering a spectacle. In the span of her career, the singer/dancer queen Sir Honey Davenport has run the gamut from pretty boy to beauty queen, and continues to switch regularly. Her ever-evolving relation to gender is paralleled by her ever-evolving name: She started as a dancing boy “Hunty,” took on “Honey” when RuPaul misheard her name at a book signing, adopted a surname when the late Sahara Davenport initiated her into full drag, and then added “Sir” to frustrate people who pigeonholed her as a Miss. “There are always new versions of me because I always become what I feel in the moment,” Sir Honey told me. “Sometimes I’m just a boy in heels. Sometimes I see an incredible dress and say ‘I want to wear that today, so I guess I’m going to tuck.’”

Sir Honey’s sentiments are echoed by Kareem McJagger, a club-kid/queen hybrid whose perennially exposed torso is manhood embodied, and whose drag is more about shock than femininity. For Independence Day, Kareem rocked red-white-and-blue eye shadow, lashes, facial hair, half-a-dozen beautifully formed abdominal muscles, and a blood red speedo. “I’m always looking for the most polished way to make people say ‘What the fuck?!’” Kareem told me. “Not just heels and a beard. Stilletto heels and a perfectly chiseled mustache.”

As my interviews progressed, I began to see drag for the first time as performance art, a creative form anchored in character-craft and provocation. I began to think that it was not gender-focused and not, as so many outsiders see it, an identity on the transgender spectrum. But then my drag-mother Bob TheDragQueen added another perspective. “I don’t buy it,” she told me. “When queens insist ‘It’s not about being a girl, I’m an artiste,’ it reminds me of straight guys desperately insisting they’re not gay. Why is that the first thing they want people to know about drag? Is it bad to be trans?”

Photo credit: Mingus Hastings

Bob’s comment made me wonder if there was a gender element I had missed. Looking back, all of the queens I had interviewed mentioned friends who had passed through drag on their way to transgender life—but no one mentioned identifying with that experience themselves. When I asked them what they wanted outsiders to know about drag identity, they offered a version of Kareem’s succinct declaration: “Drag is not a permanent lifestyle—it’s a job. The same way you take off your McDonald’s nametag, I take off my paint when I get home.” But if drag is not about gender or identity, if it’s just a job or a form of expression, why not choose a safer occupation?

For me, choosing life as a queen means taking on a lot of risk. It means fighting off bar flies who see drag as a green light for sexual aggression, or getting trailed and harassed in the street by groups of rowdy boys. And I’m not alone. While riding the subway to a gig one night, I encountered a fellow queen who said she’d had it with the harassment she suffered while walking through her neighborhood in the Bronx. “At a certain point I said, let me put a hammer in my bag to be safe,” she told me. I laughed—until she opened her bag and showed me the hammer. Drag life can be dangerous, so there must be something powerful that keeps us coming back to it.

Photo courtesy of the queen.

Indeed, for some of us, drag is worth the risk because it is part of a larger transgender exploration, a means of escaping the gender role we were assigned. Shrouded in a beard and beautifully braided blonde hair, the notoriously contrarian Azraea told me that drag can serve as a way to find a place on the trans spectrum—somewhere between the Point A and Point B of male and female, without a destination in mind. (Azraea does not identify as female, and uses gender neutral pronouns: they, them.) “Gender never made sense to me. I’ve been wearing makeup since I was a kid,” Azraea said. “So when I started drag, my performances were like therapy, helping me flesh out and work with the things I was going through.”

Azraea added that drag is a technique for provoking and challenging other people’s narrow perceptions, too. “I remember one night I was walking home in full face when I heard a man yell ‘Good Lord, that’s an ugly bitch,’” Azraea said, “and I thought, YES, gender confusion achieved for today.” Whether on stage, in the street, or on Youtube, Azraea is always looking for new kinds of “gender terrorism” that unsettle accepted notions of normal. For Azraea, drag is a tool for creating change.

Photo credit: Jovani Jimenez-Pedraza.

Which brings us to the final thing that the girls wanted America to know about drag: It’s not just clowning. Even for queens unconcerned about their gender identity, drag is a platform for shock, subversion, rebellion, social commentary—an irreplaceable forum for speaking their mind. Kizha Carr, for example, could easily support a career with her brilliant physical comedy, but she infuses her acts with biting satire. “When I first started drag I kept my numbers very simple, in line with what other people were doing,” Kizha told me, “but one of my mentors told me I was too smart to do that, and that I needed to think seriously about why I had created Kizha.”

From then on she used drag to explore something that simultaneously didn’t bother her at all and bothered her terribly: race. In a memorable number, Kizha lulls audiences into singing along with “The Wheels on the Bus,” but then pivots into a simultaneously hilarious and uncomfortable re-enactment of the Rosa Parks story, culminating in a raised black power fist. “Drag can go beyond the expected slapstick,” Kizha said. “It can be thought provoking.”

And that’s what keeps me, personally, from hanging up my wig. Sometimes it’s frightening to walk home alone after a show. Sometimes I wake up in agony from the physical stress of tucking and high-heeled acrobatics. But drag is the only forum I’ve found where I can speak candidly about loneliness, dependency, violence, gender, race, and other issues that shape my life—and, more importantly, the issues that shape the lives of spectators. Whenever I feel uncertain about drag’s importance, I remember a gentlemen who approached me after a performance about alcoholism. “You weren’t the best dancer,” he said, “but you told a story. And it was my story.”

So drag isn’t just about being pretty, or grabbing attention. And though it is inextricably bound to discussions of gender, it also transcends them. For the New York queens I interviewed, drag was a form of provocative personal expression the magnetism of which united them across diverse goals, needs, and experiences. It’s also a way to connect to an artistic lineage and a family that goes back centuries. “It’s the last underground art form,” Bob TheDragQueen said. “You can’t go to drag school. There are no drag classes. If you want to learn about drag, you have to learn it directly from another drag queen.”

And for anyone who can’t accept drag, the queens had one thing to say, summarized best by Azraea: “Not everything is made for your consumption. If you don’t like it, change the channel, close the tab, or walk away.”