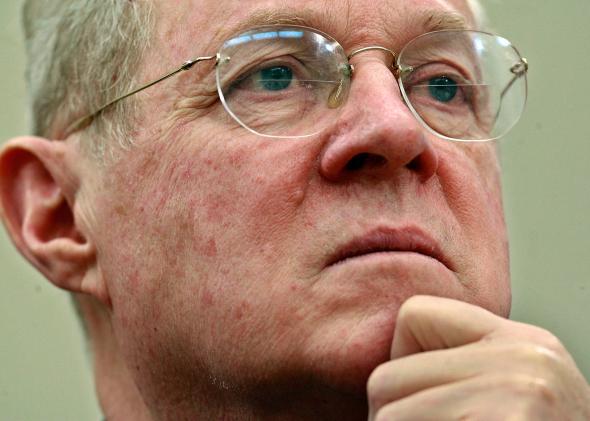

For better or for worse, the constitutional theory providing equal rights to gay people is entirely authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy. As everybody now knows, Kennedy penned the trilogy of gay rights opinions that lie behind an unbroken streak of judicial wins for gay marriage in the states. At first glance, today’s 10th Circuit opinion affirming the invalidation of Oklahoma’s marriage ban continues this streak seamlessly. But just below the surface of the ruling lies a bear trap that could mangle the legal theories that have brought gay marriage so close to the finish line.

Here’s the biggest problem with Kennedy’s gay rights opinions: They’re notoriously, ridiculously, unjustifiably vague. When Justice Antonin Scalia described Kennedy’s reasoning in the DOMA case as “legalistic argle-bargle,” he wasn’t entirely wrong. Although Kennedy bases his opinions in venerable constitutional concepts—namely, substantive due process and equal protection—he refuses to explain precisely how these concepts guide the case at hand.

Case in point: Equal protection jurisprudence dictates that laws targeting members of a disfavored “suspect class”—women, blacks—receive “heightened scrutiny.” Laws that disadvantage these classes of people, in other words, must receive stricter judicial review. Everybody who isn’t blinded by homophobia agrees that gay people qualify as at least a quasi-suspect class. Yet Kennedy has never actually described them as such, nor has he insisted that laws targeting them receive heightened scrutiny.

Instead, Kennedy has embarked on a strange jurisprudential adventure, jettisoning traditional equal protection jurisprudence for a new test: the “animus” standard. Under Kennedy’s test, laws driven solely by anti-gay animus must be invalidated as unconstitutional. In the early days, animus was easy enough to prove: The Colorado amendment Kennedy overturned in Romer v. Evans forbade municipalities for enacting their own LGBT nondiscrimination ordinances. Faced with such bald prejudice, it was easy enough for Kennedy to write that “the amendment seems inexplicable by anything but animus toward the class that it affects.”

But as lawmakers realized their blatant bigotry might not pass constitutional muster, they began dressing up anti-gay measures in the camouflage of rationality. During oral arguments in United States v. Windsor, the conservative justices repeatedly argued that DOMA was merely an attempt to create uniformity in federal marriage laws. Justice Elena Kagan eventually dispelled this nonsense, quoting from the House report that with DOMA, “Congress decided to reflect and honor collective moral judgment and to express moral disapproval of homosexuality.”

The conservatives, however, still closed their eyes to the reality of DOMA’s intent. When Kennedy wrote that the “demean[ing]” law was clearly “motivated by an improper animus,” Scalia clawed back, ridiculing the court for accepting “the lie … that only those with hateful hearts could have voted ‘aye’ on this Act.” Thanks to the startling homophobia contained in the Congressional Record, Kennedy was able to rest his claims of flagrant animus on solid ground. But observers were left to wonder: Is it possible that the backers of an anti-gay law might sufficiently mask their animus to pass Kennedy’s standard?

We may soon have an answer. In a concurrence to Friday’s 10th Circuit opinion, Judge Jerome Holmes placed the question of animus front and center, agreeing that Oklahoma’s gay marriage ban was constitutionally deficient—but stating that it was “free from impermissible animus.” Holmes explains that DOMA failed the animus test largely because it was unprecedented: Never before had the federal government so intrusively meddled with the states’ definition of marriage. The Oklahoma law, on the other hand, simply enshrined a principle—legal marriage is between a man and a woman—that had been true for centuries prior. DOMA’s animus was revealed by its breadth and novelty, Holmes says. But by merely affirming tradition, Oklahoma’s ban is untouched by animus.

Is Holmes correct? Absolutely not. Anyone who skims the literature of the Oklahoma amendment’s supporters will instantly see that their main goal was to disparage and disadvantage gay people. That’s true of every state that banned gay marriage: Ironically, the vilifying tactics that made these campaigns so effective are also what will ultimately doom them. But Holmes’ concurrence gets at a broader, more troubling question. What happens when the new generation of anti-gay warriors get smart about disguising discriminatory bills in the garb of rationality? At that point, Kennedy will either have to give his analysis more bite—or lose his position as the chief legal champion of gay rights.