Major League Baseball has failed its gay athletes and its gay fans. While quiet attempts to implement employment non-discrimination policies and a tepid embrace of ballpark LGBTQ nights show positive signs of life in baseball’s front offices, something major—and obvious—is missing in the big league. MLB doesn’t recognize its own amazing gay history. And it could change that by honoring an average baseball player.

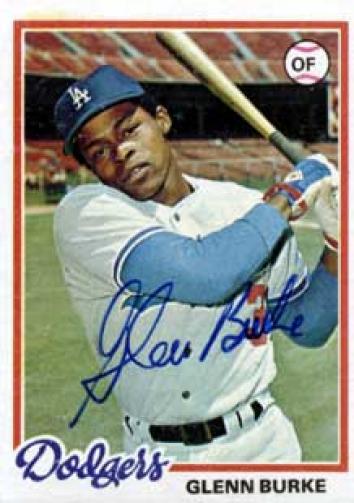

Glenn Burke’s photoless stats page on Major League Baseball’s website paints a bare-bones portrait of a mediocre career. After being called up to the majors in 1976, Burke tallied a pedestrian .237 batting average, stole 35 bases, and hit two home runs in four seasons with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Oakland Athletics. He saw five at-bats and had one hit during the 1977 World Series versus the New York Yankees. So why on earth would Major League Baseball choose to honor those numbers with a day of recognition? In a sport that reserves that honor for legendary athletes like Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente, Glenn Burke seems wholly unworthy. But his statistics don’t tell his whole story.

Numbers can’t possibly begin to explain how a tremendously talented athlete would eventually be sidelined by vicious institutional homophobia. After coming out to his teammates and managers in 1978, Burke was reportedly offered $75,000 by Dodgers Vice President Al Campanis to enter into a sham marriage. When turning down the offer—more than $312,000 in today’s money—Burke wittily replied, “I guess you mean to a woman.” Unfortunately, Glenn Burke’s fearlessness would lead to his exile from Los Angeles: That same year, he was traded to Oakland.

According to former Athletics player* Claudell Washington, manager Billy Martin was cruelly homophobic from Day 1, introducing Burke in the locker room by saying, “Oh, by the way, this is Glenn Burke, and he’s a faggot.” Much as Jackie Robinson endured unfathomable racism from fans and fellow players alike, Burke too faced the injustice of bigotry in sports. Yet as an out gay, black man in professional sports—in the 1970s—Burke was light years ahead of his time. “Being black and gay made me tougher. You had to be tough to make it. Yeah, I’m proud of what I did,” Burke recalled later in life. In a Philadelphia Inquirer interview just before his death from AIDS-related illness in 1995, Burke was defiant, declaring, “They can’t ever say now that a gay man can’t play in the majors, because I’m a gay man and I made it.”

MLB’s most significant tribute to Glenn Burke is a puff piece from 2013, which details the creation of the high five. (Burke is widely credited as the inventor of the gesture, which he later used as a greeting with fellow gay residents of San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood.) Despite his ebullient life as an openly gay man, the piece paints Burke in the victimization language AIDS activists fought so hard to combat during the height of the health crisis: “He became a tragic figure, succumbing to AIDS,” says the article, never once mentioning Burke’s sexual orientation. Burke is simply referred to as the Dodgers’ “backup outfielder.” There are no openly gay athletes in Major League Baseball today.

Glenn Burke died on May 30, 1995, just two days before June, LGBTQ Pride Month. June also represents what is best about baseball season: spring transitioning into summer, a gentle breeze, a hot dog, a beer. Opening Day and the playoffs seem miles away, leaving fans to reminisce, to unwind, to enjoy the essence of the game. With 162 games in the regular season, designating a single day during baseball’s happiest month to honor Burke’s legacy seems like a no-brainer.

Even Hollywood has taken notice. Jamie Lee Curtis was so moved by his story that she made it her mission to produce a film about his life, based on his autobiography, Out at Home. Curtis initially learned about Burke from a 2011 story about the creation of the high five that appeared in The Week. She purchased the rights to his story soon afterward. Curtis, a lifelong Dodgers fan, remembers the 1977 NLCS Championship team well, but she never knew Burke’s story. “This was a guy who just wanted to play baseball, and he was denied the right that every young athlete in the country has—just to live to the maximum of your potential,” Curtis said during an interview with Slate. Addressing the daunting tradeoff between fame and privacy that Burke faced as a gay man in the 1970s, Curtis added, “Can you imagine getting up in a Major League Baseball game and being told, ‘Swing free, but don’t do too well, because they’re going to start nosing around in your private life’?” Curtis regularly consults with Burke’s family on the project.

Ross Katz, who co-produced Lost in Translation and In the Bedroom, has signed on to write and direct the film. “Glenn blazed a trail that, in my mind, makes him a superhero. Look how hard and emotional it was for Michael Sam or Jason Collins, and look at 1978. The guts to do what he did was astounding,” said Katz.

Major League Baseball should embrace its gay history, good and bad. It’s time to bring proud gay players like Burke out of history’s closet. Doing so would empower today’s gay athletes and encourage gay kids who think sports are for straight guys only. And what better way to tell gay fans that their heroes also contributed to the vibrant history of America’s favorite pastime? MLB should embrace LGBTQ fans just as much as it has the other incredibly diverse communities that make up the fabric of baseball. In a watershed decade for gay rights, Major League Baseball has an amazing chance to showcase its true colors. It’s time to tell the story of Glenn Burke.

*Correction, June 11, 2014: This article incorrectly stated that Glenn Burke and Claudell Washington were teammates on the Oakland Athletics; their careers there did not overlap.