Yelp has confirmed its practice of deleting comments about establishments that practice homophobic discrimination—at least those from patrons who have not personally been victimized by such practices—in particular for Big Earl’s in Texas, now famous for refusing to serve “fags.”

Mark Joseph Stern recognizes the logic of the practice, but in the context of a fad for states to adopt “religious conscience” laws confirming the right to discriminate, he regrets the lack of a venue for consumers, and in particular for out-of-town travelers, to learn which businesses are keen to reject their stinking pink dollars.

Flashback to nearly 80 years ago, when African American travelers faced a similar situation. Trains, like other forms of mass transportation, enforced segregation. A growing black middle class was able to purchase automobiles, freeing themselves from such humiliation. But while African American families were not required to sit in the back of the bus when driving their own car, motorists needed to fill up their gas tanks, repair their vehicles, and eat and sleep during their journey.

African American travelers were excluded from vital services, including access to basic necessities such as toilets. They were obliged to carry their own food and even gas in their vehicles. This was not exclusive to the South. Many towns throughout the United States had “sundown” laws banning blacks within city limits after dark.

Civil rights leader John Lewis wrote:

There would be no restaurant for us to stop at until we were well out of the South, so we took our restaurant right in the car with us. … Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had made this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered “colored” bathrooms and which were better just to pass on by. Our map was marked and our route was planned that way, by the distances between service stations where it would be safe for us to stop.

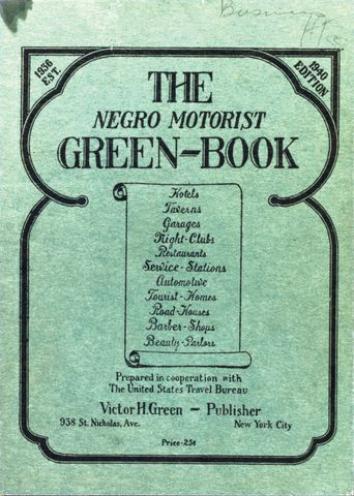

In order to assist black travelers, postal worker Victor H. Green compiled a directory of black-friendly businesses providing services for travelers, first for his native New York state, and later for much of the United States, and even parts of Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean.

Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book allowed the knowledge of people like Uncle Otis to be shared among all black motorists. The guide, first published in 1936, was updated regularly until its last edition in 1966, two years after the Civil Rights Act ended the need for such a guide (in theory at least). The act itself was made possible in part due to black travelers’ testimony about the humiliations they endured due to racial discrimination, for it was the connection between the need for all Americans to be able to travel freely and the Constitution’s interstate commerce clause that gave the Johnson administration the scope to take action on the federal level.

So far, LGBTQ people benefit from no such national protection. In an America where many seem keen to promote homophobic discrimination, do we need a LGBTQ Travelers Rainbow Book? In a way, it already exists. There is a thriving LGBTQ travel sector, represented by the International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association, which includes many gay-friendly businesses, including major hotel chains.

Among these is Marriott, which has just launched its #LoveTravels campaign for the LGBTQ market. Marriott is also a sponsor of Gay Games 9 this August in Cleveland and Akron, Ohio. This represents a striking evolution in image for a chain that despite being publicly owned, was associated with the Mormon Marriott family during the debate on Proposition 8 (see this statement from the family disputing these claims).* For several years Marriott has had consistently high, and even 100 percent, scores on the HRC Corporate Equality Index, showing the interest of this chain and more broadly the hospitality trade in the LGBTQ market.

Meanwhile, in Mississippi, businesses are responding to their state’s freedom-to-hate law by placing stickers that proclaim: “If you’re buying, we’re selling” in the windows of gay-friendly businesses.

The group’s website includes a directory of gay-friendly businesses, essentially a modern version of the Green Book. With this site and others, we have the resources to learn the information that Yelp chooses not to provide.

The parallels between such websites and the Green Book are striking, but there’s a significant difference: White Americans were almost totally unaware of the Green Book. But today, LGBTQ people are not alone in fighting homophobic discrimination. While there were (and are) white allies against racial discrimination (particularly among Jewish Americans, who had their own versions of the Green Book to deal with the anti-Semitic discrimination they faced), LGBTQ people today find supporters all around them, sometimes in unlikely places. There is nothing like having a gay child to make a parent a fervent opponent of homophobia, an advantage Jewish and African Americans did not enjoy in their fights against discrimination.

The role of allies, calls for boycotts, and the travel industry come together in a remarkable way in the current boycott of the hotels of the “Dorchester Collection,” owned by the sultan of Brunei, including the Beverly Hills and Bel-Air hotels in Los Angeles, the Dorchester in London, and others.

The boycott protests the imposition of sharia law in Brunei, including the death penalty for homosexuals (by stoning, no less).

While the boycott has wide celebrity support—they’re among the rare people rich enough to patronize these hotels in the first place—there are a few mavericks who seem to want to further enrich an already obscenely rich homophobe. Among them is Kate Middleton, who has caused an uproar by sneaking into London’s Dorchester to attend a wedding.

Another is noted political philosopher Russell Crowe, who, like some others, opposes a boycott in the name of protecting hotel employees, a preoccupation not on his mind when he threw a telephone at one of them back in 2005.

The argument that a boycott causes harm only to hotel employees, rather than to the megawealthy sultan of Brunei, misses several points, including the difference between being stoned to death and losing one’s job. And in any case, no one is calling for hotel employees to lose their jobs. A boycott is first and foremost a personal statement of principle not to support a business that one disagrees with. In the case of the boycott of the Dorchester Collection, a luxury brand, it is also to reduce the value of that brand by recalling its association with a thug of an owner. And no one is calling for the hotels to be shut or for staff to be fired: The A-list clients of the hotels simply want to keep going there with a clear conscience, once the sultan sells to a less disreputable owner.

That’s a message that Rose McGowan doesn’t get any better than Crowe does.

McGowan recently held a “gay-in” at the Beverly Hills Hotel to show her opposition to a boycott, her love for the gays, and her affection for her friend Ruth, a chambermaid, who barely earns enough to pay the rent.

Taking us full circle in an explosion of ignorance was McGowan’s guest (in fact, the guest of the sultan, since the hotel comped the bubbly for the anti-boycott party) Brian Wolk, who asked, apparently luxuriously free from self-awareness or any sense of historic irony, “Would you have told Rosa Parks not to get on that bus? That she should just boycott because they didn’t like her?”

There may soon be an online LGBTQ Travelers Rainbow Book, and it could indeed be useful for gay consumers and their friends—at least the ones less confused about the stakes than Russell Crowe and Rose McGowan.

*Correction, June 10, 2014: This post originally stated, erroneously, that Marriott was a family-owned company.