When the 2014 FIFA World Cup kicks off June 12 in Sao Paulo, Brazil, there will not be one openly gay man among the 22 players on the field. Indeed, 32 nations will participate in the monthlong soccer extravaganza and not a single one of them will have an out gay player in their squads.

Soccer’s face is heterosexual and heteronormative. A supermodel is as essential an accessory for the modern player as a supercar. The number of openly gay professional players can be counted on one hand. Those players who have come out, such as Robbie Rogers of the LA Galaxy, have attributed their periods of denial to the aggressively homophobic atmosphere in the locker room, while institutionally, little has been done to assuage the notion that soccer doesn’t care about its gay players. The 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups will take place in Russia and Qatar, respectively, after all.

The foregoing is used to assert that soccer is one of the last bastions of unchallenged intolerance toward gay people—Ben Summerskill, chief executive of the British LGBTQ campaign group Stonewall called soccer “institutionally homophobic,” for example. Within a culture where much stock has long been put in certain conceptions of masculinity, brotherhood, and competition, the argument goes that a space cannot exist for soccer players who fail to conform to traditional gender stereotypes, that soccer fans would not embrace a gay player.

But this idea is based on an outdated understanding of soccer and the characteristics of today’s average fan. True, there are no openly gay international players right now, but it’s not the 1980s anymore—the football hooligan is dead. Over the last 20 years, soccer in Europe and the United States has largely kept up with and undergone the same processes of economic, social, and cultural change that the rest of society has experienced and enjoyed, including on matters of race, sex, and gender.

Through globalization and commercialization, soccer has altered beyond recognition. On one hand, the removal of borders between people and capital has unlocked club sides in Europe to talent from South America, Africa, and Asia. Second- and third-generation immigrants have become integrated into national teams, mirroring the countries they represent. On the other, stadiums are no longer the domain of the white working-class male: The middle classes, women, ethnic and sexual minorities, and families have over time been welcomed into the match-day experience.

This acculturation has had the effect of neutering soccer’s exclusive, harsh, and thuggish image. No longer does soccer center on strength and brute force, a game played by the tallest and widest, the ball punted upfield for players to wrestle over. Imported players and coaches have brought their own ideas with them—players are more fleet of foot, graceful, and skilful; the game more considered, tactical, and intellectual.

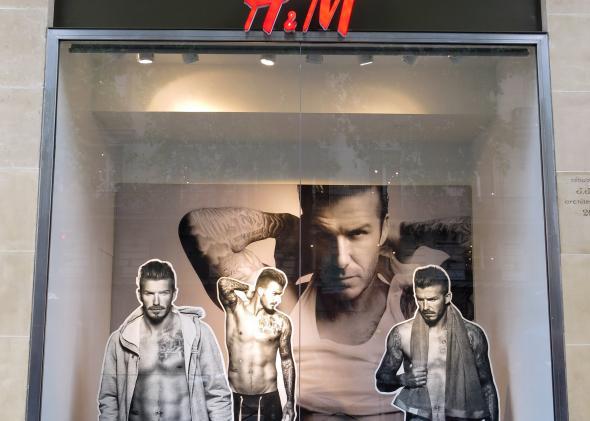

Off-the-field changes have been crucial, too. From David Beckham wearing a sarong and appearing on the cover of the British gay magazine Attitude to Cristiano Ronaldo launching his own range of underwear, players serving as role models for their adoring fans have helped alter what it means to be male. Metrosexual soccer stars have made it acceptable for supporters to consider their hair, their body, or their threads. Once confined to more marginal subcultures, sensitive stylistic concerns have spread into the mainstream.

Soccer has also fostered an environment where public displays of male intimacy are par for the course. The stadium is a protected zone in which men are able to hug and kiss, embrace and clamber upon one another, without judgement and in a way that would be unacceptable and downright peculiar in everyday life. Soccer as a male bonding experience begets not only comradeship and male solidarity among fans but close, personal relationships—bromances, if you must—between players.

Globalization and commercialization have had negative consequences for soccer, too (these include ticket-price inflation and the erosion of club identities), but at least it can be said that its gift has been to chip away at the closed-mindedness and rank bigotry that almost killed the game during the 1970s and ’80s when, in the United Kingdom for example, the neo-Nazi National Front would leaflet stadiums and plant gangs on the terraces intent on causing violence. Racism and xenophobia among fans are gradually withering away. Problems concerning race and gender are no longer dismissed as emanating from supporters but, rather, are viewed as structural issues that require serious and meaningful reform from within.

Homophobia is acquiring the same opprobrium as racism, and attitudes toward sexual identity are keeping pace with societal change. A recent survey conducted by Stonewall and Swedish app developers Forza Football found that a majority of soccer fans in countries as diverse as the United Kingdom, Brazil, India, Israel, Mexico, and the United States would feel comfortable if a player on their national teams came out as gay. Soccer fans, therefore, are no less enlightened than the societies in which they live.

More than that, this evolution is a reflection of the ability of modern soccer to integrate players on a very meritocratic basis—fans, by and large, are able to accept anyone for anything, provided they can produce on the pitch. “I think football is there to provoke moments of happiness, excitement and positive experiences in people, no matter where they come from, what colour skin they have, what religion they are or what their preferred sexuality is,” Arsene Wenger, the manager of top London club Arsenal, remarked recently.

It is supposed that soccer isn’t ready for a gay star. Rather, the problem is that the principle of whether soccer is ready hasn’t been tested. “It would be good if four, five, six people come out and after that nobody speaks about it anymore because they just think it is people who live their life like they want to live it,” Wenger added. If an international player were to come out during or after the World Cup, they would find a sport that is more than ready to take them as they are.