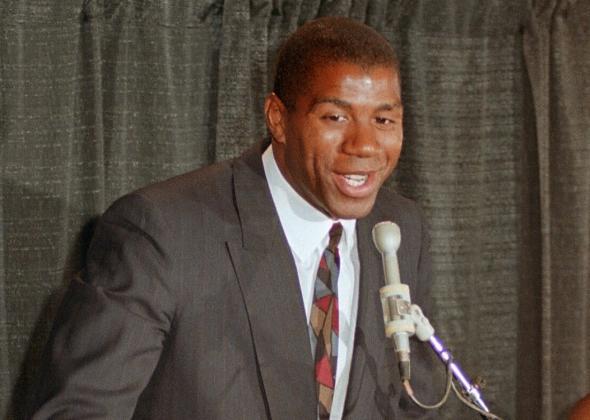

On Nov. 7, 1991, the face of HIV/AIDS changed forever when basketball star Magic Johnson announced he had received a diagnosis that at the time was almost universally associated with gay men. In front of a packed press conference at the Los Angeles Forum, Johnson revealed something that seemed incomprehensible to many: Anyone—“even me,” he said—could contract HIV.

Jeff Pearlman’s new best-selling book Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s is not about Johnson and HIV/AIDS. But in chronicling Johnson’s rise to NBA stardom as part of one of sport’s greatest empires, it lays the foundation for the impact of that November announcement, and a fascinating sports story becomes so much more. Johnson played 13 seasons—his entire professional career—with the Lakers, and his $25 million, 25-year deal, signed in 1981, was one of the first of its kind. He made an already good team great, personifying the era that became known as Showtime. As veteran player Spencer Haywood succinctly summarizes: “Magic Johnson was our wake-up call.”

Certainly, Magic isn’t the only key figure in Pearlman’s story; Kareem Abdul-Jabbar led the team long before Johnson was a Laker.* But the book begins with Johnson’s arrival and ends with the HIV announcement. That Johnson bookends the saga surprised even Pearlman. “I didn’t know how the book would begin until I started writing it,” he told me. “I didn’t know the breakdown of the chapters, or who would emerge where, or what would follow what.” One thing he was sure of, however, was the finale. “What I always knew was how it would end. I just wanted the final moment of the narrative to be Magic announcing he had HIV. That was the end of Showtime.”

The book’s final pages read very differently from the rest of the romp through the Lakers’ fast break heyday, which had been filled with visits to the Playboy Mansion, parties at Magic’s own palace, and late nights at the infamous Forum Club, where wives were discouraged but women were plentiful. In the last chapter, simply titled “Shock,” the detail-driven page-turner becomes a blunt chronicle of events. Pearlman respects that his readers know what is unfolding: At a routine physical for a life insurance policy, Johnson tests positive. The timeline Pearlman develops from that point—the Lakers holding the news until Johnson himself can reveal it, colleagues and friends flying in to support him—leaves no room for poetics, but it is an emotional read, no matter how familiar the story.

Pearlman says he found no other way to write it. “It wasn’t a matter of changing up writing styles,” he says. “I think some writers get all pretentious and airy about their writing. It’s not really my thing. I just needed to wrap things up. And this was the obvious wrap point.” He even avoids using the word HIV until the last sentence of that chapter, when Johnson takes to the microphone: “Um, because of the HIV virus that I have attained, I will have to retire from the Lakers today.”

While Showtime isn’t a book about HIV in America, Pearlman recognizes that the Lakers’ position in the sports world enabled the most significant turning point in HIV/AIDS awareness. Without Showtime, and Johnson’s role in it, who knows how long it would have taken for HIV/AIDS to lose some of its stigma.

For Pearlman, the impact of the announcement was more about Magic than the team. “I see Magic as the closest we’ve ever had to a second Muhammad Ali—a global sports icon who transcends sports with a human touch, a beautiful smile, a gift to relate with people of all races, economic classes,” he says. “Magic is loved by folks who don’t give a shit about basketball, just as Ali has moved millions of non-boxing enthusiasts. The reason people were shocked wasn’t because a Laker had HIV. It was because Magic—a beloved figure—had it.”

Comparing Magic to Ali is both interesting and problematic. There are differences of course: Ali was a determined social activist, while Magic was thrown into the political spotlight by his diagnosis. But like Ali, Johnson transcends sport and is known as much for his charisma and charm as the no-look passes that Pearlman details so well. And it was his star power in the world beyond basketball that helped normalize discussion of safer sex practices and to dispel a lot of the secrecy and shame that surrounded HIV/AIDS. “Without Magic, HIV/AIDS awareness doesn’t speed up as it did,” agrees Pearlman. “It was something to fear; to stay away from. Magic changed that, or at least started to change that. He was a universal face. He was heterosexual. He was big and strong and famous and powerful. It sounds sort of cliché and goofy, but it was along the lines of, ‘If Magic can get this, anyone can.’ ”

Today, Magic Johnson, a successful entrepreneur and social activist, is still the most prominent example of a person living with HIV. More than two decades after his diagnosis, he demonstrates what money, science, and celebrity can accomplish in a relatively short period of time. As Jeff Pearlman deftly demonstrates in his engaging book, Johnson’s is a sports story. But it is one that reminds us how and why sports matter.

Correction, March 14, 2014: This post originally misspelled Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s last name.