Where does sexual orientation come from? It’s a tired question and, frankly, a tiresome one, since it always seems to lead us back to the same familiar (and likely inextricable) tangle of science, culture, and ideology. That said, it’s at least worth trying to keep the terms of the debate, well, straight, and “social construct”—the notion that sexual orientation is a modern invention, with which a person might or might not choose to affiliate—is a concept that has been greatly misunderstood.

To wit: last month, the religious journal First Things published a controversial essay by Michael W. Hannon called “Against Heterosexuality,” which offers an ultra-conservative take on the issue of whether our sexual orientations are natural conditions or chosen constructs. Hannon’s piece is just the latest in a number of recent articles in the “choice wars.” Brandon Ambrosino, writing for the New Republic, set off a small firestorm in January when he described his homosexuality as a choice, not a biological fact. His article provoked vitriolic responses from, among others, Gabriel Arana and Slate’s own Mark Joseph Stern. Clearly, the biology vs. choice (or nature vs. culture) debate remains a point of serious contention within the LGBTQ community and beyond.

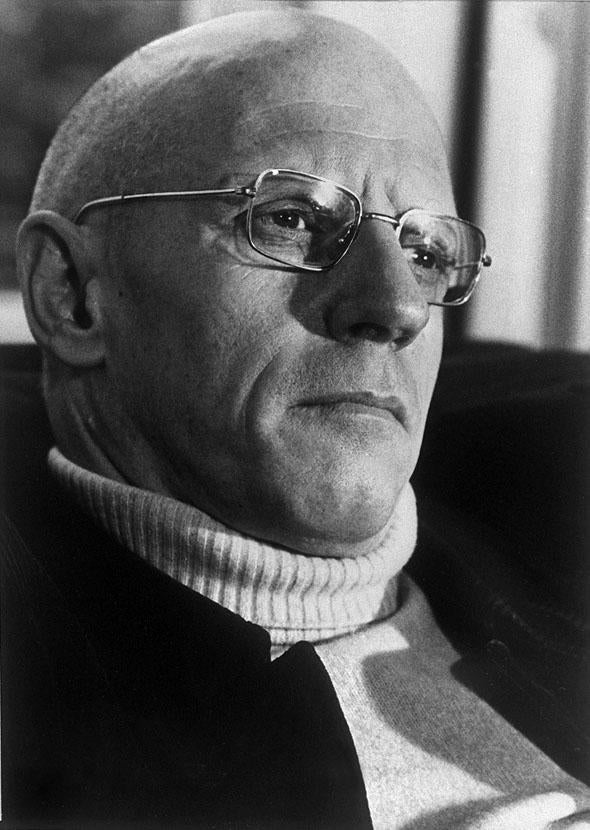

But does “construct” mean what these new adopters think it does? Though Hannon and Ambrosino have different political endgames, they both invoke a very unlikely ally: Michel Foucault, the French philosopher who’s known as the grandfather of queer theory and a central architect of the “construct” conception of sexuality. Though Foucault died in 1984, his History of Sexuality, Volume I is still mandatory reading in LGBTQ studies courses. His theories about where sexuality comes from have been hugely influential in academia for decades. But Foucault is also responsible for a lot of the confusion surrounding the biology vs. choice debate—largely because his work been taken out of context by liberals and social conservatives alike. While Hannon’s essay is a particularly disturbing piece of work (see Stern’s scathing take-down for more), all of these popular misinterpretations tend to muddy the political waters, and risk obscuring Foucault’s most important contributions to our understanding of sexuality.

Let’s start with a quick primer. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault writes that Western society’s views on sex have undergone a major shift over the past few centuries. It’s not that same-sex relationships or desires didn’t exist before—they definitely did. What’s relatively new, though, is 1) the idea that our desires reveal some fundamental truth about who we are, and 2) the conviction that we have an obligation to seek out that truth and express it.

Within this framework, sex isn’t just something you do. Instead, the kind of sex you have (or want to have) becomes a symptom of something else: your sexuality. Though Foucault traces the origins of this shift back to the 16th century, our modern conceptions of sexuality really take root during the Victorian era, when the psychiatrist replaced the priest as the confessional authority figure. The science of sexuality was born—along with the elaborate systems of classification that allowed doctors to establish a divide between “normal” sexualities and “deviant” ones (like homosexuality).

How did one detect, diagnose, and correct deviancy? Parents, teachers, and doctors had to maintain constant vigilance over young children, so as to identify abnormal tendencies as early as possible. As they grew up, children would internalize these procedures of examination, until eventually they could be counted on to carefully monitor and report on their own thoughts, feelings, and desires. Foucault and people like Hannon agree on this point: in modern Western society, we experience a great deal of pressure to share and interpret our sexual impulses. Every desire, no matter how fleeting, must be catalogued and made to fit into our overarching sense of who we are. Queer people may experience this pressure in a more intense and immediate way than heterosexuals do, but nobody is immune. You might think you’re straight, but you’d better keep a very close eye on things, just in case. And even if you cross your t’s, dot your i’s, and say “No homo” at all the right moments, it’s still possible that others will be able to detect something in you that you didn’t know was there.

For Foucault, the obsession with figuring out the truth of our sexualities is a trap. After all, how do we know when to stop? Who can tell us when we’ve peeled back the final layer of social constraints and discovered our truest, most authentic selves? Foucault—who, by the way, identified as gay—knew that knowledge can never really be separated from power. Sometimes knowledge can be empowering, like when we take the language that was once used to diagnose us and turn it into a political rallying cry. But that knowledge can also be wielded against us, often with very concrete and painful results. Thinking and talking endlessly about our sexualities doesn’t really get us closer to figuring out who we “really are.” It does, however, generate plenty of evidence that can be used to monitor, control, and discipline us when we deviate from the norm.

This is why Foucault, who spent his life studying criminals, so-called sexual deviants, and the mentally ill, never tried to analyze these people the way a doctor or psychologist might. He wasn’t interested in figuring out what environmental or genetic factors caused them to turn out like they did. In fact, he refused to ask or answer those kinds of questions at all. When an interviewer inquired whether he thought homosexuality was an “innate predisposition” or the result of “social conditioning,” Foucault replied, “On this question I have absolutely nothing to say. No comment.” Pressed for details, he explained that he would not use his position of authority to “traffic in opinions.”

In the end, Foucault wasn’t interested in settling the question of whether sexual orientation was biologically determined or, indeed, socially constructed. What he wanted to understand was how sexuality came to be the question—the one thing we believe we have to answer before we can move on to anything else.

However, that does not mean he thought we should, or even could, dismiss these categories out of hand. And this is where Hannon and the other choicers deeply (and, it should be said, perhaps willfully) misunderstand Foucault: “Social construct” doesn’t mean “not real.” Try that logic out on the 81 percent of LGBTQ students who report experiencing verbal or physical harassment at school, or the estimated 40 percent of homeless youth who identify as gay and/or trans: These are people who know firsthand that these “fragile constructs,” as Hannon puts it, still have tremendous real world power. We live in a world that values and rewards certain identities and punishes, often brutally, those who don’t fit that mold. Concepts like sexuality aren’t just names that we can take on or cast off at will. They are structures built into the very fabric of modern society, and they shape, from Day 1, how we understand the world and our place within it.

If I believed Hannon was actually interested in dismantling what queer theorists call “compulsory heterosexuality,” I’d be the first to enlist in his campaign. As theorists of race and gender have long recognized, however, the dream of easily declaring ourselves “post”-anything often conceals a desire to sweep structural inequalities and long histories of violence under the rug. To say that sexuality doesn’t or shouldn’t matter is to deny many people the reality of their lived experience. It is also to ignore this important truth: that while society may construct these categories, these categories also construct us, and not only in negative ways. Identifying as queer isn’t simply a matter of swapping your straight hat for a feather boa. For most of us, it is a lifelong process of crafting bodies, relationships, and selves that can make our lives fuller, our art more vibrant, and the task of existing a little less destructive.

To me, making space for that kind of work seems like a better use of our collective energy than spinning our wheels at the biology vs. culture impasse. Changing our ideas and institutions is possible: that’s what The History of Sexuality helps us see, by showing us that our categories are not set in stone. After all, we arrived here, and that must mean we can still go elsewhere—but in order to do that, we have to follow Foucault’s lead and start asking some different questions.