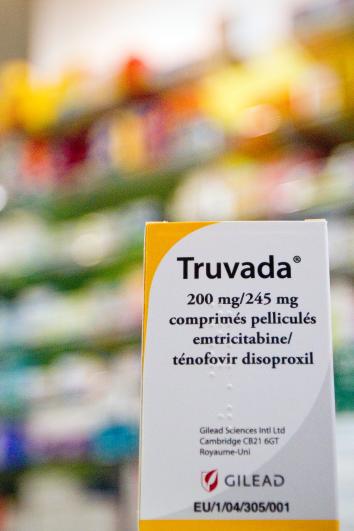

Truvada is a largely unheralded miracle drug, a fantastically effective once-a-day pill that prevents HIV infection with minimal side effects. It’s wonderful news, then, that the pill may soon be available to all Britons at no cost through the country’s National Health Service. But it’s deeply disappointing to learn that Truvada’s approval may be held up by prudish and condescending researchers.

As the Times reports, a two-year NHS pilot trial of Truvada will wrap up later this year, at which point the drug should be licensed as a pre-exposure prophylaxis, provided for free at state-run health clinics. But there’s a hitch: Sheena McCormack, the leader of the trial, is concerned about “the impact this might have on behavior.” According to McCormack, “It could lead to a lot more risk-taking and sexually transmitted diseases, as well as perhaps also drawing in people who were currently using condoms consistently into dropping condoms.” Implicit in her statement is that even if Truvada does exactly what it’s supposed to do—prevent HIV infection—the general public cannot be trusted to use it responsibly.

This is doubly foolish. Truvada simply doesn’t lead to riskier sexual behavior, or “sexual risk compensation.” That patronizing assumption has already been debunked, which is why the FDA dismissed it when approving Truvada for U.S. sale. But let’s assume for the sake of argument that Truvada did lead to sexual risk compensation, that men who take it use condoms less reliably and engage in riskier sexual activity. Even if this were true—and again, it’s definitely not—Truvada would still be an important, life-saving drug.

McCormack—and presumably the NHS—is primarily worried that Truvada will lead to a drop in condom usage, which will in turn lead to an increase in other STIs, like syphilis. Because Truvada doesn’t lead to a drop in condom usage, this fear is unfounded. But if it were true, Truvada would still be worth it. When it comes to STIs, HIV is in a class on its own in terms of health impact and expense. Syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea can be treated with antibiotics; herpes can be easily suppressed; genital warts can be burned off; but HIV is forever—and AIDS is always lurking around the corner. An HIV-positive person must take a variety of expensive drugs throughout his lifetime to stay healthy and remains at heightened risk for myriad serious diseases. Preventing HIV infection in the first place, even at the hypothetical cost of other STIs, would still produce a net benefit.

There is one STI, Hepatitis C, that rivals HIV in seriousness, as the Times piece notes. But including this point in the parade of horribles is something of a red herring. Hepatitis C is rarely spread through sexual contact; the transmission rate is less than 1 percent per year of a relationship with an infected person. One factor that does significantly raise your risk of contracting Hepatitis C? Already having HIV. Reducing HIV rates in the general population, then—perhaps through Truvada—may actually help to curb Hepatitis C transmission rates, not increase them.

A final, frequent objection to Truvada, thus far unmentioned by the NHS, is the peril of forgetfulness: As soon as patients miss a dose, they lose protection, and it’s easier to forget to take a pill than to forget that you’re not wearing a condom. This, admittedly, is a major concern. But it’s one that should be addressed by medical counseling and supervision, not squeamish moralizing. That would be the practical way to handle the problem—but as the Truvada wars have illustrated, pragmatism rarely wins the day when it comes to sexual health. We should be using every tool we have in the fight against HIV, and hand-wringing over condom usage—which began dropping long before Truvada—does no one any good. NHS researchers are wrong to fret that Truvada will trigger an uptick in other STIs. But even if their paranoia were based in reality, the drug’s life-saving potential would clearly justify any opportunity costs the NHS fears.