Much has been made of how quickly the LGBTQ rights movement has gained traction, particularly in comparison with other civil rights struggles. This is sometimes noted with a tinge of liberal self-satisfaction, the implication being that in the past 50 years we’ve evolved into a more tolerant and forward-looking culture. But in light of continued discrimination against African-Americans in hiring and housing, barriers to women succeeding at the highest levels of many professions, and laws passed to harass and intimidate Latino communities, it seems a bit naive to imagine that people’s hearts have changed so drastically. Another potential explanation is that gay and lesbian Americans are part of families and communities all across America. But the women’s rights movement was one of the slowest to gain traction—and absolutely everyone has women in their families. So, what made the struggle for gay rights different? Gays and lesbians may be indebted to an institution we’ve long looked down upon: the closet.

Often perceived as a barrier to equality, at times the closet was anything but. Instead, it allowed a gay fifth column to flourish, far behind enemy lines, among the privileged and the powerful in American society. Even as out and outed gay people were being marginalized and discriminated against, some closeted gays (mostly white, male, affluent ones) were able to achieve positions of power, wealth, authority, and influence. Though small in number, these individuals were ideally positioned to influence their fellow elites in ways that other marginalized groups, whose access to the upper echelons of society was severely limited, could only dream about.

This is not meant to suggest that traditional activism was unimportant to the struggle for gay and lesbian equality. Quite the contrary: Before the Stonewall riots begat the modern gay rights movement, it seemed unlikely that the status quo of hiding—and of meekly submitting to occasional acts of harassment and violence by law enforcement—would ever change. An activist front in the battle for acceptance was a necessary precondition for subsequent developments. But activists on the outside looking in could never have brought about change so quickly on their own; they needed closet cases embedded in the existing power structure to serve as catalysts.

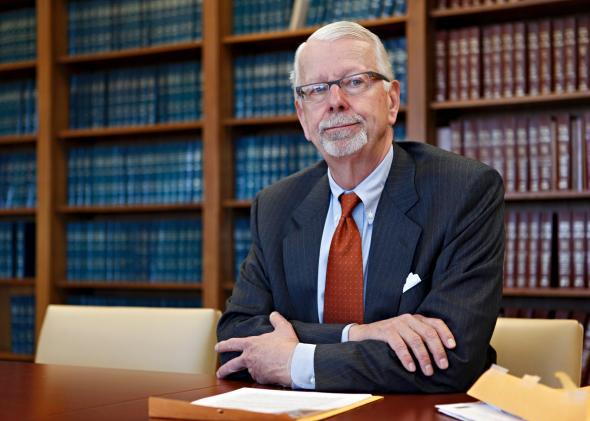

In 2014, even Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has gay friends. But without the closet it’s hard to imagine how that could have come to pass. In order to get from there to here, we needed people like Vaughn Walker. You may remember Walker as the federal judge who ruled California’s Prop 8 unconstitutional. He was first nominated to the federal judiciary by no less a conservative than Ronald Regan, was then blocked by Democrats (due, in part, to his perceived anti-gay stances), only to be re-nominated by George H. W. Bush and eventually confirmed. Walker didn’t come out of the closet until 2011, after he’d retired from the judiciary.

Closeted politicians have also been a major boon for gay causes. Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin became the first out candidate to be elected to the House of Representatives in 1998, but her way was paved by the likes of Gerry Studds, D-Mass., (outed in 1983); Barney Frank, D-Mass., (came out in 1987); Stewart McKinney, R-Conn., (a bisexual who died of AIDS in 1978); and Steve Gunderson, R-Wis., (outed in 1994). When these men entered Congress in the ’70s and early ’80s, it would have been impossible for openly gay men or lesbians to be elected. Voters (and, perhaps more important, political donors and party officials) became more comfortable only when presented with the fait accompli of gay politicians at work serving their districts.

Of course, there are also famous counterexamples of closeted politicians who have opposed gay rights at every turn, but there’s no reason to believe that the majority of closet cases have been hypocrites. Steve Gunderson was known for his pro-gay policies even before his outing, for example, and in 1996 he became the only Republican representative to vote against DOMA. (It seems unlikely that Wisconsin voters in would have elected him on such a platform back in 1980, however.)

The influence these gay fifth columnists exerted over their elite friends and colleagues may well have begun long before they came out, or were outed, as gay. I like to picture Vaughn Walker or Steve Gunderson dining with Republican muckety-mucks, shaking hands with major GOP donors, and discussing legal issues with conservative lawyers and judges. Even tepid, timidly expressed pro-gay views could have been a powerful force for change in such forbidding venues. By being in those rooms, these men had the chance to subtly influence attitudes at the highest levels of American politics long before same-sex marriage became a mainstream issue. Later, when they eventually came out of the closet, it meant that some powerful people found that they already knew gay men as friends and colleagues. These were not abstract concepts, like “poor people,” “women,” or “blacks,” but living human beings who they’d grown used to thinking of as equals.

While it’s certainly true that gays and lesbians are in families and communities across America, the outlook for issues like marriage equality would not have been nearly so good if they’d not also been deep inside the inner circles of presidents, CEOs, and Supreme Court justices. The difference has been felt in the relatively easy path to acceptance gays and lesbians have had, in the relatively cordial tone of the debate around gay rights, and in the swiftness of our legal victories. We may have been on the right side of history, but history can use all the help it can get, even if it comes from some unlikely sources.