In November, Grove Press published a 50th-anniversary edition of John Rechy’s City of Night, a landmark novel about a young hustler who travels the country plying his trade. In beautiful, lyrical language Rechy describes the era’s gay bars and pickup zones as well as the personalities who moved through them.

June Thomas recently spoke by telephone with 82-year-old Rechy about his writing career and the world’s endless fascination with hustling.

Slate: I know that in the initial response to the book, reviewers were startled by its sexual frankness. By today’s standards, it doesn’t seem shocking. You don’t go into details about what the narrator does with his scores, for example.

Rechy: I never thought that the book was scandalous. I wrote it from my experiences, so when it came out, and the reaction was so harsh, I really was taken aback. I actually left the country to avoid being involved in those discussions, and that increased the sense that I didn’t exist.

Slate: What a weird conclusion to draw.

Rechy: The New York Review of Books started it, then the New Republic discussed it, then The New Yorker took it up, and then the Village Voice. All questioning whether I existed or not. It was mind-boggling.

I was in Puerto Rico, reading in newspapers about impostors claiming to be me, getting thrown out of bars, and all kinds of stuff. That just made me want to keep private even more.

Slate: Nowadays, there’s this whole genre of stunt books, where people undertake peculiar tasks specifically to get a book deal. Was there any way, even subconsciously, that you took up hustling in order to have something to write about?

Rechy: No, I never intended to write about it when I was in the midst of it. What happened was that I wrote a letter to a friend after I had a terrible time in New Orleans at Mardi Gras. It seemed good, so I rewrote it and sent it to the Evergreen Review and New Directions, and both of them accepted it. The editor of Evergreen Review asked me if it was part of a novel, and I said yes. There was no novel at all. It was only then that I began writing City of Night.

Slate: As I understand it, you carried on hustling even after the book was published?

Rechy: After the book came out, I needed even more to be hustling. I felt unfaithful because I’d left it. Even now, I still feel this weird thing about the characters. I felt guilty because I had an out, and the other people stayed. That world was a dead end.

Slate: Did you feel that you had exploited the real people you had turned into the characters for the book?

Rechy: I wish I could say I didn’t, but it’s too gruesome to say otherwise.

Slate: It’s remarkable to me that you carried on hustling. As an outsider, you get the impression that this is a job that people do because they have no alternative. But you did have an alternative.

Rechy: I would go through periods, brief periods, where I would stay away, get a job. One time, in San Francisco, I had a job, and I looked out the window onto a very busy corner, and I saw a very obvious connection going on between an older man and a younger man. I tell you, something just drew me, and I walked out on that job right that moment. I didn’t even change. It just seemed like I had to go. It wasn’t even the money. It was the excitement of it. And yet there were all those terrifying times that I did include in the book. I didn’t romanticize it. I thought I gave a pretty accurate account. That part of my life was very real, very exciting. I don’t regret any of it, not at all.

Although that world has moved into the Internet, it remains the same. The scene is exactly the same. The same lures, the same dangers, the same terminal aspect of it.

Slate: It strikes me that writing and hustling have a lot in common. They’re two of the oldest professions. You’re generally your own boss. You work on your own schedule. They’re also lonely jobs. Did they seem similar to you?

Rechy: Yes. Writing is hustling of another kind.

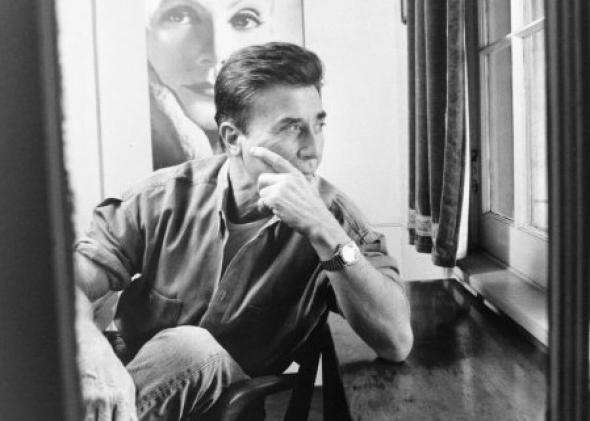

Photo courtesy of Grove Press

Slate: Nowadays we often talk how Facebook and other social media mean that people will never be able to escape their young selves, because what they shared on the Internet will always be findable. That’s true for you, too. You’re always going to be known as a guy who was a hustler. Is that frustrating to you?

Rechy: That does annoy me. When my last book came out, David Leavitt was given it to review for the New York Times. It was as if 50 years had not passed. You know what headline the New York Times gave that review? “Hustler“! I’m a writer who hustled. I’m not a hustler who wrote. I don’t think this happens to other writers. Why should their subjects dominate their identity?

Slate: It’s very limiting. At the same time, though, I’m aware that I’ve asked a lot of questions about it. It’s dramatic. It’s something unusual that fascinates people. But I’m sure it’s frustrating.

Do you feel that the book is finally getting its due from the critical establishment?

Rechy: Some time back I received the PEN USA Lifetime Achievement award, and recently there was a conference on my work in Merced. People gave papers, it was really something. Then UCLA had a celebration for me on City of Night. There are two Ph.D. candidates doing their doctoral dissertations on me. I’m Mexican-American, but for a long time I was pushed out of any references to Mexican-American writers. It was easier to come out as a gay man than it was to come out as a Mexican-American. They didn’t want me—a Mexican-American gay man—but that’s changed. Now I’m being acknowledged.

This interview has been edited and condensed.