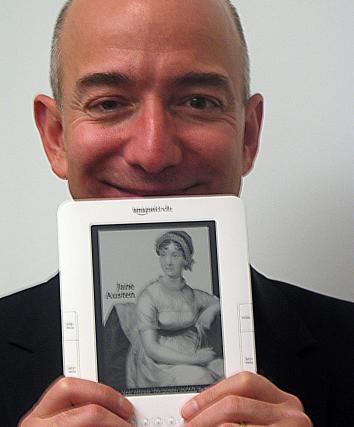

Brad Stone’s brand-new history of Amazon, The Everything Store, chronicles the company’s breakthroughs and missteps and paints a fascinating, sometimes terrifying portrait of its messianic, profit-eschewing founder, Jeff Bezos.

The Everything Store says the company name originated with Bezos poring through the A section of the dictionary and having an “epiphany” when he came to the entry for Amazon:

He walked into the garage one morning and informed his colleagues of the company’s new name. He gave the impression that he didn’t care to hear anyone’s opinion on it. … “This is not only the largest river in the world, it’s many times larger than the next biggest river. It blows all other rivers away,” Bezos said.

But there was already a bookstore of that name: Minneapolis’ Amazon Bookstore Collective. And in 1999, that feminist bookstore, a community fixture since 1970, sued Amazon.com for trademark infringement. Although Amazon.com had been operating since 1995, during the 1998 holiday season, the number of people confusing the two operations cost the bricks-and-mortar store considerable time and money. General manager Barb Wieser told the Corporate Legal Times, “We were getting 20 or more phone calls a day from people thinking we were Amazon.com. They were looking for books we didn’t have. They wanted to come down and get them. We fielded so many calls it felt like we were working for Amazon.com.”

It’s no surprise that Amazon.com contested the suit, but its lesbian-baiting legal tactics in a pretrial deposition shocked many observers. As Katharine Mieszkowski reported in Salon, Amazon.com’s attorney repeatedly asked a bookstore collective member “under oath about her own sexual orientation and that of the staff.” Questions included: “Have you had any interest in promoting lesbian ideals in the community?” “I’ll ask you this, are you gay?” and “Are any of the employees of the bookstore gay?”

According to an Amazon spokesman, the lawyer’s questions were intended to establish that the two companies were in “different businesses,” with Amazon.com catering to a “general-interest” audience, while Amazon Bookstore Collective was “lesbian-owned and operated, catering to the lesbian community.” Whatever the merits of this approach, it was a PR nightmare. According to Mieszkowski: “Amazon.com’s own customers are sending outraged e-mails to the company demanding answers. The idea that Amazon.com would focus on sexual orientation in a trademark lawsuit apparently does not sit well.” She noted that Amazon.com responded to customer complaints with “an e-mail attempting to justify the company’s legal strategy and to tout its progressive values.”

Perhaps that’s why, when the lawsuit was settled in November 1999—the Minneapolis bookstore assigned its common-law rights in the Amazon name to Amazon.com, which then licensed it back to the store—Amazon.com’s press release quoted Weiser praising the online retailer’s politics. She said: “As a part of working with Amazon.com to resolve this dispute, we have learned about its long-standing commitment to diversity. Its policies of explicitly forbidding discrimination based on sexual orientation and offering same sex benefits to all of its employees make it a leader in the corporate world in that regard.”

At the time of the settlement, both parties declined to discuss financial details, but in 2008, when the collective sold the store to customer Ruta Skujins (who then had to change the name, according to the terms of the legal agreement), Wieser acknowledged that the collective had received a small cash settlement from Amazon.com that helped “keep the business going a little longer.” In 2012, Skujins’ store, now known as True Colors, went the way of so many independent bookstores and closed its doors.