Someday, somewhere in Washington, D.C.—perhaps on the National Mall, kitty-corner across Maryland Avenue from the sinuous, sandy-colored Museum of the American Indian, or tucked behind the sprawling complex of the Natural History Museum—there may sit a National Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Museum. That might sound surprising, considering that sodomy was illegal in the District until 1993, but Tim Gold, CEO of the Velvet Foundation, is convinced the time is right.

“I’m hoping to see this in the next five years,” he says confidently. That might seem like an ambitious timeline for an institution with an initial funding goal of $50 mllion to $100 million, but he and his husband, high-end furniture magnate Mitchell Gold, have been quietly working on the museum project since 2007. That’s when they first conceived of the Velvet Foundation as a 501(c)3 nonprofit dedicated to “creating the National LGBT Museum in Washington DC.”

Before 2007, Gold spent most of his professional life working in the Smithsonian at the National Postal Museum, and he credits that experience—in a roundabout way—with generating the idea for the LGBT Museum.

“I thought we could do a great exhibition on James Smithson, who is the benefactor of the Smithsonian Institution,” he recalls. But when he suggested the idea, it didn’t go over well, “because he was British, and he was potentially gay, and that doesn’t really fit into what they wanted to project.”

Yes, you read that right: The founder of the institution that conservatives threatened to defund and destroy over the display of work by queer artist David Wojnarowicz, was quite possibly gay himself, according to Gold’s own research. (Even more intriguingly, a recent Smithson biography, The Stranger and the Statesman, suggests that Smithson’s nephew, who was originally slated to inherit the fortune that funded the Smithsonian, was also gay.) This is a perfect example of the kind of story that Gold hopes the museum will one day tell, stories “of the LGBT communities as a part of—not apart from—the American experience, where the intersections of diverse cultures, shared by diverse people, define us as individuals and as a nation.” And what could be more American than reveling in the fact that the founder of a great American institution was possibly gay and definitely British?

In many ways, the idea of a national LGBT museum is sharply divergent from the general trend of LGBT history organizations. “From the ‘70s to now-ish, it’s been about collecting, preserving, and investing,” says Anna Conlan, a Ph.D. student and adjunct professor of art history at Hunter College, whose master’s thesis at Columbia focused broadly on queer museology. Private individuals and grass-roots organizations such as New York’s Lesbian Herstory Archives, which was founded in 1974, preserved the legacies of LGBT people and communities long before it was possible to even consider an institution on the scale of what the Velvet Foundation is proposing. Over time, these groups “start having museological functions,” Conlan says—curating displays from their collections, hosting speakers, etc. Some even develop into museums of their own, or create museum offshoots, as is the case with New York’s Leslie + Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, which started as a private collection by Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman, and the San Francisco GLBT History Museum, which was created from the collection of the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society.

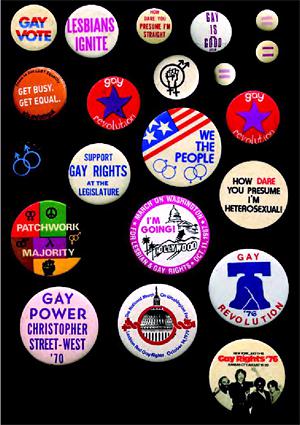

Photo courtesy National LGBT Museum

Still, making that transition can be hard, as archives and museums serve different, though related functions. Archives tend to be more in-group oriented, with a primary audience that is congruent with their collections focus, while museums target a wider populace. Archival holdings usually involve more paper and fewer objects, and instead of telling stories about history, they allow visitors to discover these stories on their own.

In Conlan’s view, LGBT communities need both long-running, grass-roots organizations focused on historical preservation and newly formed organizations that follow a “more traditional model” of historical presentation. But Conlan’s enthusiasm comes with a caveat—one shared by almost everyone I spoke to: It has to be done right. Or as Gold himself puts it, “It’s like building a cathedral. Once it’s done, you can’t tear it down and say, let’s start over.”

To that end, the Velvet Foundation has embarked upon a long planning process, which included focus groups with a number of sub-communities within the larger LGBT community. Conlan herself participated in one for lesbian- and bisexual-identified women, and two main concerns were captured in the report from the meeting: First, that the primary organizers were all wealthy white men, and that other members of the LGBT community need to be deeply involved in the planning process, not tacked on at the end. And second, that the museum must embrace a broad vision of social justice.

These concerns were echoed by Amy Sueyoshi, the associate dean of the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University and co-curator of the GLBT History Museum. In her view, history is an important part of the psychic armor that allows marginalized people to survive in a difficult and often hostile world. “The way I think about the history of people of color or of queers is to imagine situations that are much worse than the situation I’m living in, which gives me courage and inspires me to keep going,” she says.

She hopes that a national LGBT museum will embrace a wide spectrum of LGBT experiences and identities. “I want it to be very vigilant in its mission so it doesn’t just produce stories about gay white men,” she says, and so that all the stories they tell are layered and complex, not just “histories of heroism.”

As with most things in life, whether the museum is able to pull this off has to do, in part, with where the money comes from. In creating a national institution, Sueyoshi points out, “there’s this tension of ‘how much are we really going to be able to talk about things’ that might offend folks who have power in America. … I want the national museum to not always mount exhibits that will bring in the largest financial audience.”

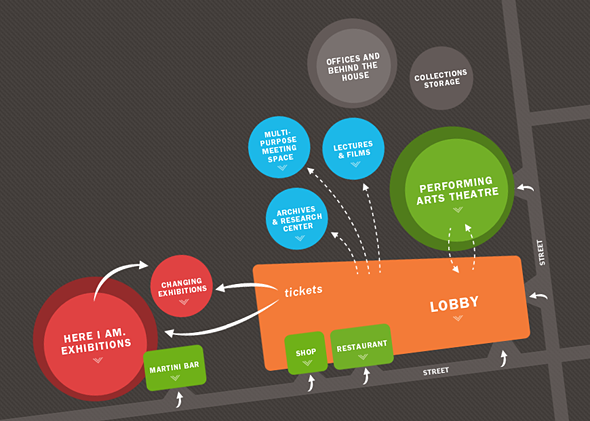

Image courtesy National LGBT Museum

When asked, Gold talks at length about attempts to ensure staff diversity, and particular stories that the museum hopes to tell that don’t feature gay white men—like the story of civil-rights organizer Bayard Rustin. He is resistant, however, to what he calls “check-box identity politics,” and only time will tell if the museum can adequately address the issues raised by the focus groups. But when it comes to the question of funding, and the strings it can put on an organization, he is of one mind with Conlan and Sueyoshi. “If we go the route of an old-school capital campaign, we would be in danger of leaving out the most marginalized people,” he says. Years of experience and feasibility studies have convinced the Velvet Foundation that raising funds from private individuals is both doomed to fail and likely to leave them unduly influenced by the whims of rich, gay white men.

Instead, the Velvet Foundation plans to utilize a new form of for-profit business called a “benefit LLC,” which is similar to a traditional real-estate company, except that it has a “social benefit” built into its mission. Whereas a traditional LLC is mandated to pursue the highest return for its investors, and its staff can be penalized for behaving otherwise, a benefit LLC has both shareholder return and its social benefit (in this case, securing a home for the National LGBT Museum) as its prime directives. Thus, the creation of Oliver-Grayson Holding Co., which the Velvet Foundation hopes will operate as a successful Class A real-estate company—while simultaneously finding a home for the museum.

In the end, Gold is adamant that this strategy will work—or perhaps it is more accurate to say he is philosophically opposed to pursuing any other strategy. “I would rather not see a museum,” he says, “than see a museum that left out the stories that need to be told the most.”