The mail is about to get a little gayer. As the Harvey Milk Foundation and the U.S. Postal Service confirmed last week, pioneer pol (and biopic subject) Harvey Milk will be featured on a new postage stamp next year. This is certainly a well-deserved honor, but I’ve got one quibble: Most reports observe that Milk will be the “first openly LGBT official ever featured on a U.S. stamp.” As is so often the case, openly is the key word in that statement.

None of the gay, lesbian, or bisexual politicians who have previously appeared on U.S. stamps publicly acknowledged their queerness. During the 1990s I was a member of the Gay and Lesbian History on Stamps Club (I’ve been on the cutting edge of cool for quite some time), in part because I loved to read the explanations of why the group had added new names to its list of LGBT people who had received philatelic recognition. In March 2011, for example, the GLHSC publication the Lambda Philatelic Journal discussed whether Texas politician Barbara Jordan qualified. After acknowledging Jordan’s own silence about her sexuality, the Houston Chronicle obituary’s mention of her long relationship with a woman, and a biographer’s claim that there was “no conclusive evidence” that Jordan was a lesbian, the LPJ’s editor simply noted, “It was well known in the Texas gay and lesbian community that Barbara Jordan was a member.” (The GLHSC also counts Presidents James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln as playing for the queer team.)

The USPS has put several lesbian, gay, or bisexual people on stamps over the years—including Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, Samuel Barber, Elizabeth Bishop, Isadora Duncan, Langston Hughes, Frida Kahlo, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Cole Porter, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, Rosetta Tharpe, Andy Warhol, Walt Whitman, and Tennessee Williams—and there are surely many others who qualify but whose inclusion might be disputed.

Take for instance, Willa Cather. Earlier this year, The New Yorker’s Joan Acocella discussed how the long-enforced (and recently ended) ban on quoting verbatim from Cather’s letters made it impossible to confirm that she was a lesbian, even if that was the accepted view of Cather scholars. (And as Acocella notes, it was mostly a matter of feelings rather than actions; Cather may have died a virgin.)

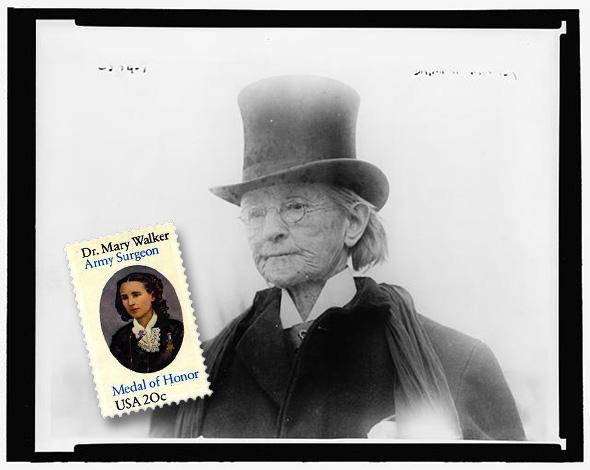

Or consider Medal of Honor recipient Mary Edwards Walker, put on a stamp in 1982 in recognition of her service as a Civil War surgeon. Walker was wed shortly after she graduated from medical school in 1855, but the marriage was short-lived, and for much of her life Walker, who preferred to dress in men’s clothing—and was arrested several times for doing so—dedicated herself to the causes of women’s suffrage and “dress reform.” Washington, D.C.’s Whitman-Walker Health, which primarily serves the LGBT community, is named for her and Walt Whitman, and as the clinic’s website observes, “Ironically, the stamp portrays her wearing a frilly dress and curls.” Was Walker a lesbian, as determined by contemporary standards? Probably not. Was she queer? Most definitely.