When Wayne Koestenbaum catches on one of your sentences, he marks it with an exclamation point. Longer comments (a legitimate explanation, a brief discussion of whether the mark was born of pleasure or horror, even a basic definition of the !) are generally not forthcoming. The urgency of the line gesticulating furiously toward a dot in the margin makes Wayne’s point—his whole point—forcefully enough: A consciousness was here, and, at this particular juncture, it exclaimed.

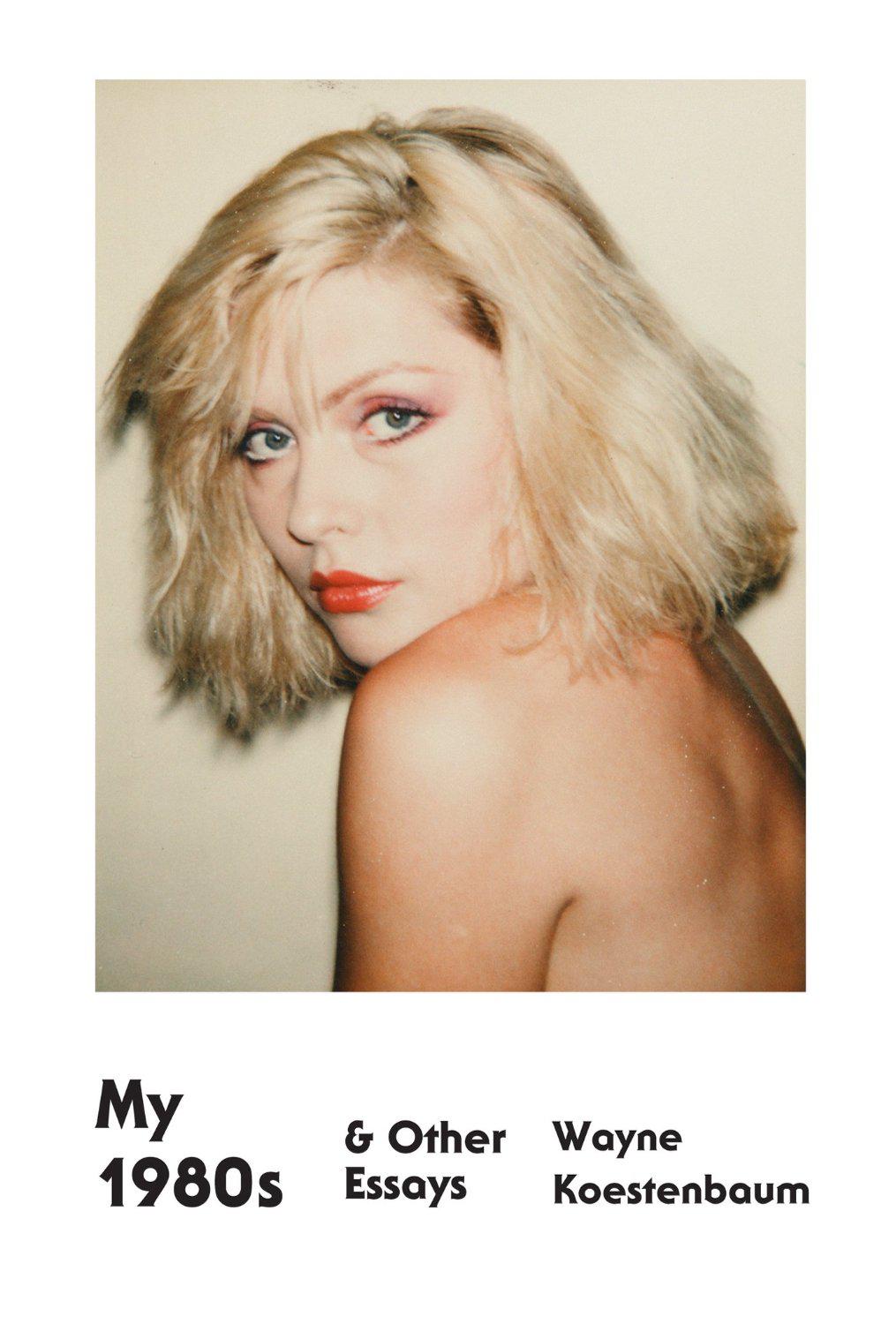

I have been caught on Wayne’s work as a critic, poet, academic, and painter—or more accurately, his unmistakable way of working, medium be damned—for many years now; I’m familiar with his notational habits due to my somewhat surreptitious attendance of his CUNY seminar on Gertrude Stein, Roland Barthes, and Fernando Pessoa a few semesters ago. He called the course “The Desire to Write,” which, it turns out, is also the name of the final essay in his new and very queer collection of exclamations, My 1980s & Other Essays.

To get what’s going on in this motley collection of auto-ethnographic idylls, aesthetic pleas, artistic amicus briefs, Oulipian exercises, and cheek-reddening dream journals, here is the question we must ask: What characterizes this desire to write, at least as it tugs on Wayne? Despite his reputation for being overly confessional, formally iconoclastic, or obsessively weird, his desire seems to be of very old stock. See Michel de Montaigne, inventor of the modern essay, prefacing the 1580 publication of his works:

“I have set for myself no goal but a domestic and private one. I have had no thought of serving either you or my own glory. … I have dedicated [my essays] to the private convenience of my relatives and friends, so that … they may recover here some features of my habits and temperament. … Thus, reader, I am myself the matter of my book; you would be unreasonable to spend your leisure on so frivolous and vain a subject.”

As an infant, the essay was a selfish, temperamental thing, crying out for sympathetic readers but really not caring who happened to overhear its idiosyncratic tantrum; only later in life did it become trained in the respectability of measured clarity. In My 1980s, Wayne simply reiterates his appreciation of a good primal scene.

Being a noted student of pornography, Wayne wisely keeps most of his essayistic ejaculations to satisfying clip-like lengths. And even when certain pieces go on, much of the text is really just “story,” tension-building material that ultimately serves to support some money shot of critical insight. Indeed, that coming is such a perfect analogy for Wayne’s ecstatic style of looking, reading, and listening probably explains why many reviewers of My 1980s thus far have struggled with the rigor, validity, or even usefulness of his trysts therein with the likes of Hart Crane, Cindy Sherman, and James Schulyer—orgasm, after all, eschews justification, getting off is caused, tautologically, by whatever gets one off.

But to conclude from this that Wayne’s work is merely masturbatory is a well-worn mistake. Like Montaigne, he does seem to have a partner in mind, a secret fraternity of kinsmen who, though perhaps personally unmoved by the particular preoccupations he has chosen to indulge in these pages, will be aroused at least by the general form and thrust of his desire. As a gay man, I know when I’m being cruised—eying the copy of My 1980s over on the coffee table right now, I’m beginning to suspect that the various subjects gathered inside are better understood as a literary wide-stance, hospitable to all interested parties, than a fetish-specific peep show. Forget Wayne’s specific glosses on Frank O’Hara, the films of Lana Turner, and, multiple times, himself; let’s talk instead about the queer kind of criticism that he applies to them all.

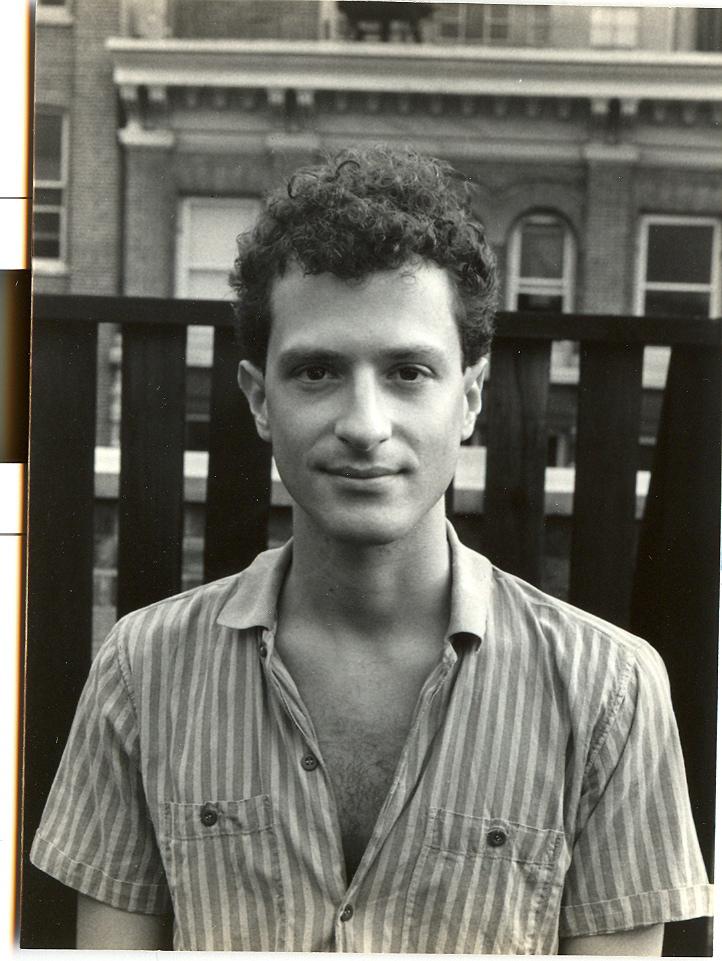

Wayne Koestenbaum in 1985.

Photo by Louisa Campbell.

Wayne, gay, understands cruising, too. In an essay early in the collection about the importance of “nuance” (a subject I’ve written about in Slate before), he describes the ancient exchange of glance and glimpse as “a state of sexual readiness akin to readerly readiness—a willingness to pick up codes.” A practiced cruiser scans for quiet signs—sartorial, physical, energetic—that a stranger on the train or in the park might be interested in a connection. For Wayne, the ideal encounterer of art (written, painted, or otherwise) will scan a work for nuances with which to connect, regardless of the creator’s consent. If the formula for cruising is Seeker(s) + Signal = Sex, a vulgar formula for Wayne’s criticism might be Consciousness + Nuance = Exclamation.

But when anonymous sex is over, the parties, usually wanting to stay that way, zip up and head out. Wayne’s talent, by contrast, is lingering, like a Law & Order: SVU officer, over the scene of the aesthetic assignation. His criticism only begins with the spontaneous thrill of recognition; its meat, a particularly neurotic cut, is made from the dogged struggle to account for that eruption. Of course, queer people—especially gay men—have been on this trip for decades (if not centuries) via avenues like camp, decorative arts, and diva worship. (The queer predilection for “hyper-aestheticism” is, after all, a natural, adaptive, and wondrous response to being made cultural outsiders; from this rare perch, we’re able to see what is in all its gorgeous and gory detail—who could blame us for carrying on about it?) What Wayne brings to the caravan is some serious humanities erudition and, more important, a level of commitment to the project that can, again like Montaigne, afford few “thought[s] of serving either [the reader] or [the writer’s] own glory.” Wayne writes: “Does any of this information matter? I am not responsible for what matters and what doesn’t matter. Offbeat definition of materialism: a worldview in which every detail matters, in which every factual statement is material.” Emphasis is, unapologetically, mine (or yours) to assign.

Washing one’s hands of these kinds of responsibilities is freeing, but also frowned upon; if you refuse to provide the security blanket that a clear didactic intention represents in criticism, you’re liable to be left out in the cold. Later, Wayne writes: “Giving advice makes me melancholy: Is anyone listening? Will anyone be improved, or moved, by my admissions?” Reviewers and fans of Wayne’s criticism tend to celebrate (or at least tolerate) the exuberance of his prose, to laud with varying degrees of enthusiasm his rambunctious dedication to radical subjectivity. But whether he’s giving advice, giving a close-reading or giving a jaunty look, I’ve always sensed an undercurrent of melancholy in Wayne’s work. Not sadness, exactly; more like a yearning for, again, that perfect fraternity—one that he knows may well not exist.

One day in class, as a way of getting us to understand the nuance, Wayne put on a record: Anton Webern’s 4 Pieces for Piano and Violin. We were, in a Cageian way, meant to listen more for the silences than the sounds. As the music played, I watched Wayne’s face: The melancholy was there then, too, on the corners of his soft smile and in the eyes. It spoke of a quiet realization that few of us, perhaps none of us, could really get what tweaked him about Webern’s silences. However, that wouldn’t stop him from exclaiming about them, till the end of the period and beyond.

This is a queer and perhaps useless use of one’s intellectual energies, to be sure. But it’s a kind of criticism—evaluative not only of art and artists, but of the basic ways we may choose to engage with the world—that deserves more than a spot in the margins.