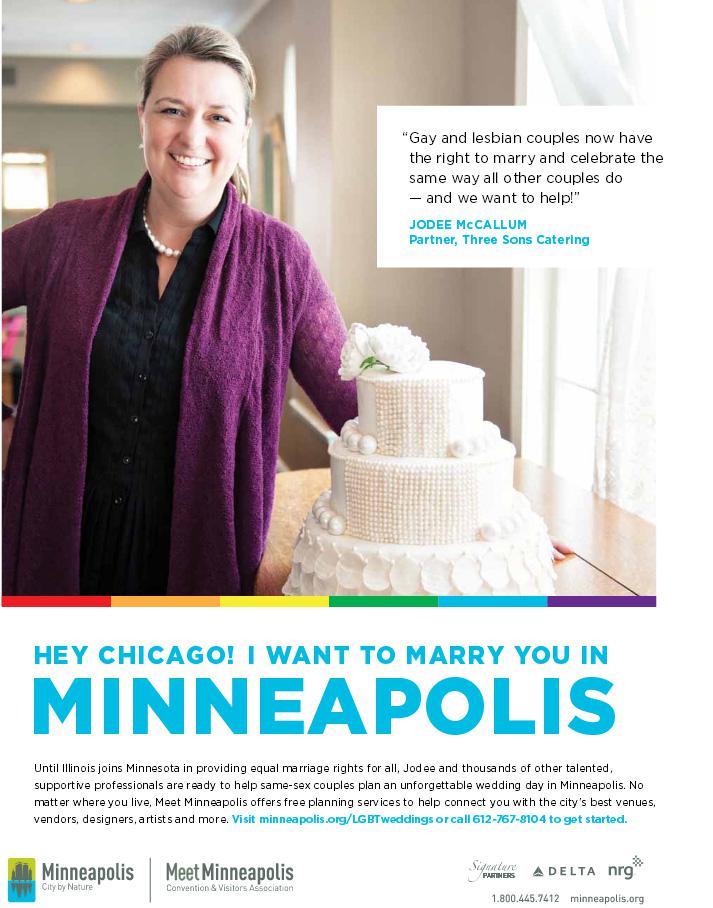

This month, Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak launched a somewhat charming, somewhat shrewd campaign called “I Want to Marry You in Minneapolis,” entreating gay couples from nearby states to his city to get wed. Rybak’s point is partly moral—he’s knocked Chicago as a “Second City in human rights” and chastised Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker for denying equality to Wisconsinites—but it’s primarily pragmatic. As Rybak readily admits, the wedding industry is a big business, and out-of-state gay weddings could bring Minnesota millions of dollars in new revenue.

Rybak’s campaign isn’t the first instance of marriage tourism, but in a post-DOMA world, it’s certainly the most meaningful. Thanks to the Supreme Court, gay couples who obtain an out-of-state marriage license aren’t just marrying symbolically: Their union is now recognized by the federal government, meaning they can file joint federal taxes, receive Medicare nursing home benefits, sponsor a spouse’s green card, and receive veterans benefits, not to mention about 1,100 other rights. A gay couple might get married in Minneapolis, but they’ll stay married when they cross back into Wisconsin.

This is an extremely weird state of affairs. It’s also a novel one. When marriage tourism began more than a decade ago, the ceremony itself was mostly a metaphor. A gay couple that married in Canada might feel the elation of a wedding, but they’d also feel the crushing reality of returning to a country that treated them, legally, like strangers. Since 2004, marriage tourism has been more of a domestic affair, but a couple that wed in Washington, D.C., still lost their rights when they crossed the Potomac into Virginia.

With DOMA dead, however, marriage tourism is suddenly a real and practical option for gay couples—one that makes a mockery of our patchwork of state-by-state marriage laws. Legally speaking, the current system is nightmarishly muddled: Thirteen states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government are currently at odd with 37 other states on a major legal issue, leading to a bizarre and headache-inducing mess for pretty much everybody. Can the Pentagon require gay members of the Texas National Guard to receive marriage benefits if state law seems to forbid it? Can the federal government recognize same-sex marriages performed by rogue county clerks in New Mexico? DOMA was overturned less than three months ago, but uncertainties like these are already clogging up the country’s courts.

If history is any guide, this situation won’t last for long. Throughout America’s existence, questions that pointedly divide the states have been resolved by federal mandate. Slavery and women’s suffrage were considered to be the exclusive purview of the state before they were resolved by war and constitutional amendments; the 14th Amendment, ratified in response to the Civil War, explicitly outlined new rights to be granted to every citizen, no matter their state of residence. And it’s not only the grave issues of the day that tend to attract the attention of the federal government: Congress has intervened to unify state laws on matters as trivial as the drinking age.

The marriage equality split likely won’t be solved by a constitutional amendment or an act of Congress. It’s much more plausible that the issue will return to the Supreme Court in the near future. And anybody who reads the tea leaves of U.S. v. Windsor knows that individual states’ same-sex marriage bans are probably on constitutional life support. In the meantime, Rybak’s campaign, and the phenomenon of marriage tourism, serve as an odd reminder of Americans’ rapidly shifting gay rights landscape—a landscape that can’t maintain its current contours for much longer. A gay couple in Chicago might be inspired by Rybak to obtain a marriage license in Minneapolis. But if they wait a little longer, they might not have to go farther than their own city hall.