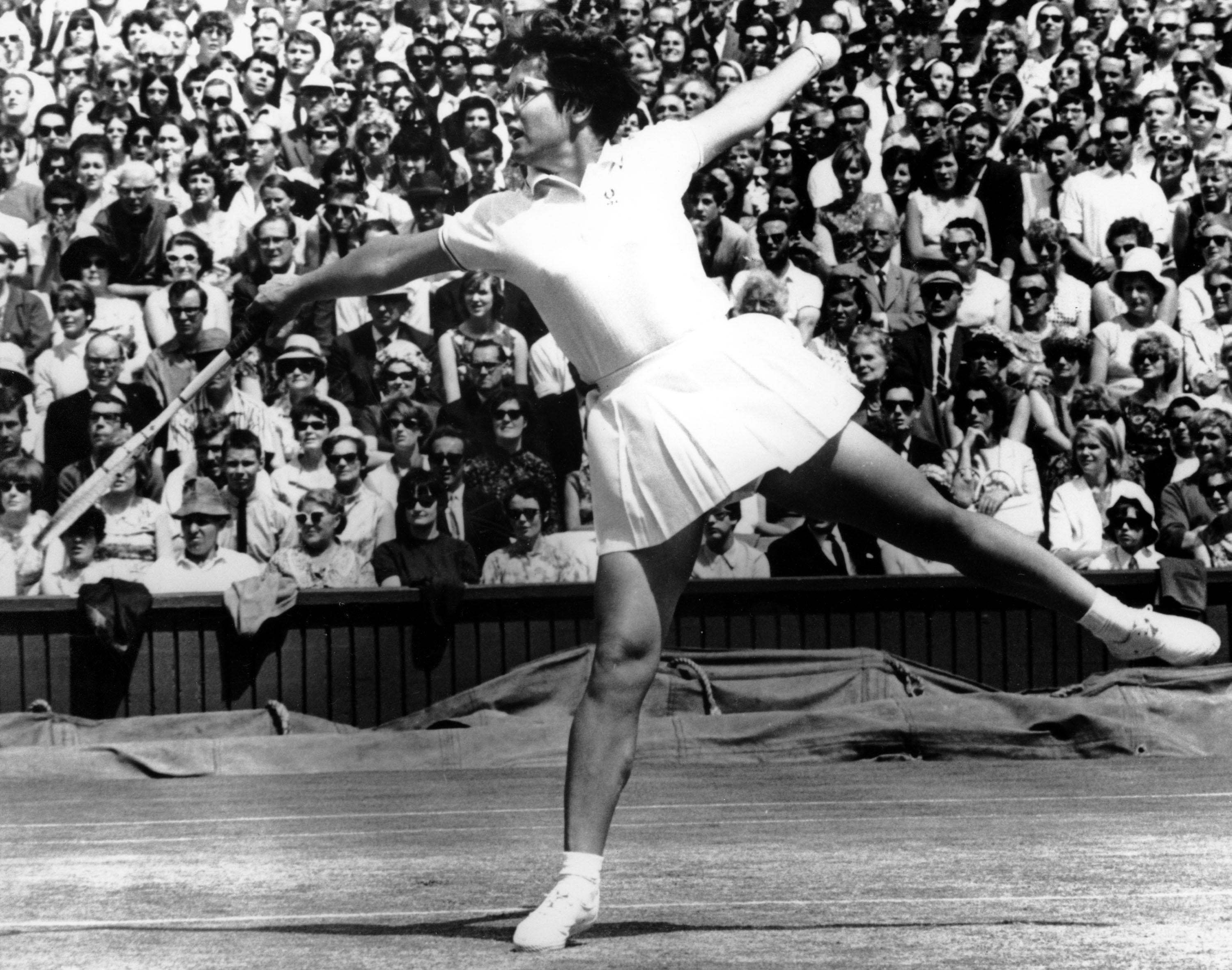

PBS’s American Masters series is dedicated to profiling the nation’s most successful writers, musicians, and artists—the kind of people whose life stories are already well-known to public-television viewers, in other words—so it’s tough for its documentarians to move from the merely informative into the realm of surprise. But this Tuesday’s episode, a profile of tennis star Billie Jean King (notably the first time an athlete has received the American Masters treatment), contains some truly shocking footage that everyone should see.

The contours of King’s life story are familiar to anyone who cares about women’s sports: a blue-collar childhood that left her always feeling like an outsider in the country-club world of tennis; astonishing success on the court; and an extraordinary record as the ringleader of various efforts to gain respect—and respectable paychecks—for female players. And, of course, on Sept. 20, 1973, at the age of 29, she won a circus-like Battle of the Sexes against 55-year-old Bobby Riggs, an over-the-hill hustler who took great pride in calling himself a “male chauvinist pig.”

The Riggs match has been the centerpiece of several books, and it takes up about a third of this new documentary. (Recently, it was also the subject of an overblown ESPN takedown.) As someone who spent her teenage years obsessed with BJK, I’ve always thought the episode received way more attention that it deserved—why should a one-night gimmick outshine the rest of King’s career? I changed my mind when I watched the American Masters film, which contains several clips from TV news features that I’m sure were completely unremarkable when they first aired in the 1960s and ’70s.

First come a series of vox pop interviews with British tennis fans who are asked who they’d like to see win Wimbledon. Anyone but Billie Jean King, they reply—she’s far too competitive and unfeminine. Then Bobby Wilson, a British guy whose sporting successes are at best chihuahua-sized compared with BJK’s mammoth achievements, blithely announces that “the game is possibly not quite as attractive today” because of players like King, who charge around the court “very much like a man, rather than the old days where you had girls who looked exceptionally graceful.” Next comes another British TV piece about Billie Jean’s husband, Larry. “Mr. King plays an average tennis game and a better than average waiting game,” the narrator intones. “He’s become accustomed to walking a few steps behind his wife. Larry’s had enough of tennis, but as yet he’s not put his foot down about his wife’s future.” (If you don’t speak old-school sexist, that means that a guy whose wife’s tennis earnings put him through law school hasn’t yet ordered her to stop pursuing her career.)

Judging from these and other clips, three or four decades ago, there were two ways of covering women’s tennis: You could pass judgment on a player’s femininity, or you could ask her why she was still single. (If she was married, the question was why she hadn’t retired yet.)

This collage of quotidian sexism establishes why the Riggs match mattered so much: It wasn’t just about one loud-mouthed hustler; it offered King a rare chance to volley back at chauvinism.

This footage also helped me understand why King, a fearless rabble-rouser who at the peak of her career fought a series of pitched battles against her sport’s establishment, took so long to come out as a lesbian. She had realized that she was gay before the Riggs match in 1973, she says, but she kept it a secret until 1981, six years after she retired from singles play, when she was outed by a female ex-lover who sued her for “galimony.” The outing was her “darkest moment,” King says. She was worried about losing endorsements—and she did lose them—and of the disapproval of her parents, who, she says, were “very homophobic” at the time. (Her 91-year-old mother is “fantastic now,” she says.) But most of all, she was worried that if the face of women’s tennis was known to be a lesbian, the sport would suffer. In the early ’70s, coming out was no joke for anyone, but now that I’ve seen these clips, I have a better understanding of the extra pressures King faced.

I’ve always wondered how many more trophies King might have hoisted if, in her prime, she had focused on her game instead of dedicating so much time to activism. I also can’t help thinking that she might have been even more successful if she hadn’t had to devote so much energy to securing the closet door.