A little book in Madeline L’Engle’s Austin Family series, The Twenty-Four Days Before Christmas, had an outsized effect on our family’s Advents when I was in elementary school.

Our copy of Twenty-Four Days was actually a compilation of torn-out pages from a woman’s magazine that had serialized the story; my mother pasted the magazine pages into a stapled-together construction-paper booklet. It was one of the first books we read every year, when my mother brought out the Christmas book collection early in the month, and we wore that construction paper out.

In Twenty-Four Days, Vicky Austin is 7 years old, sandwiched between two siblings. The book starts in early December, and Vicky’s mother is expecting a fourth child sometime in early January. Twenty-Four Days takes readers through the family’s Advent tradition: Every day of December, they do one Christmas-y thing. The book was published in 1964, and the Austins live in a happy household in a bucolic New England town—their “Christmassy things” are exceedingly wholesome. The Austins make stuffed dates, pick berries and pine cones in the woods to make decorations, listen to special Christmas records, and put Christmas candles in the windows. Vicky worries over her role as the angel in the Christmas pageant, and all of the Austin children scour the forecast for snow.

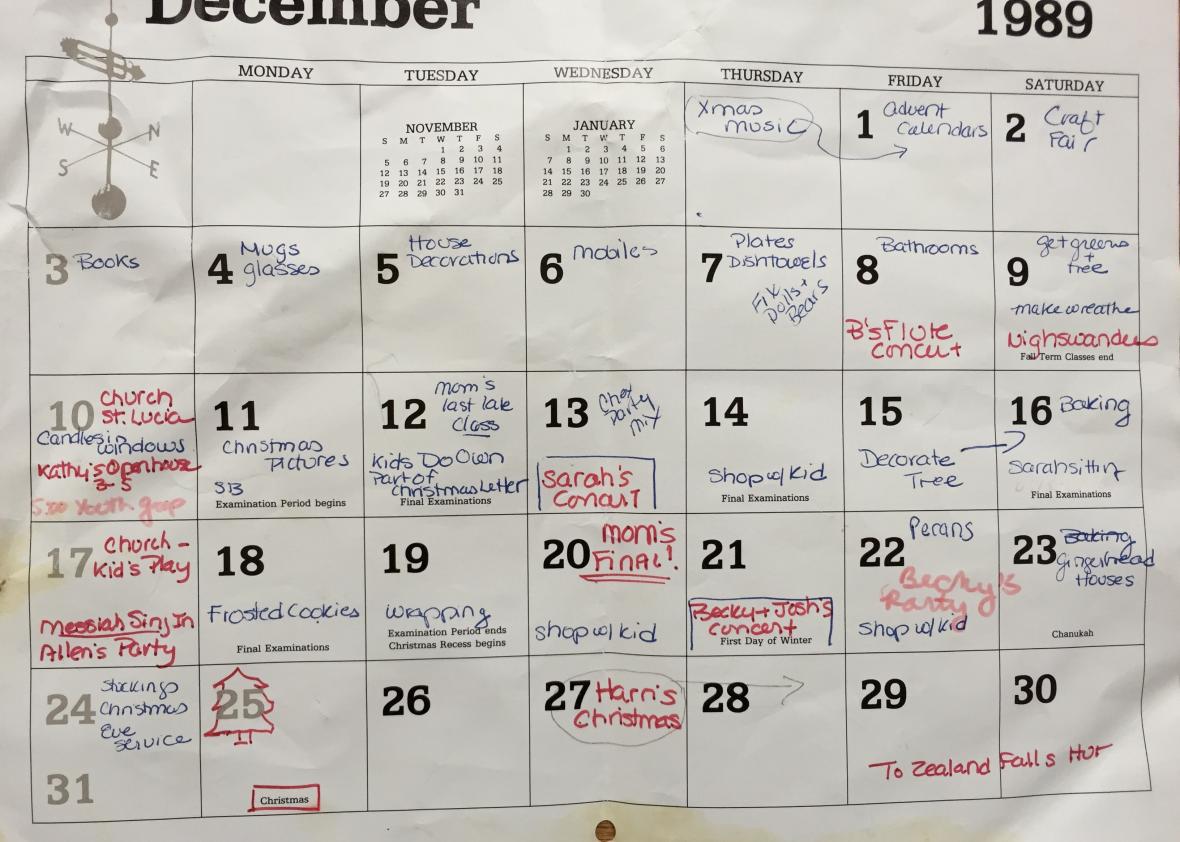

Sometime in the late 1980s, we started doing as the Austins did. My mom recently sent me a photo of her December calendar page from 1989, with a Christmas activity noted on each day. Some were community events—the elementary-school craft fair, our various Christmas concerts, church for the St. Lucia service—and some we did at home. Mom used the first full week of December as the time when we would get all of the Christmas geegaws out of hiding and put them out around the house. Mugs and glasses one day, the Christmas mobile another, plates a third. (You may have guessed that my mother loves Christmas. She is the kind of person who has special holiday hand towels for every bathroom in the house; we put them out on Dec. 8 of that year.) Later in the month, there was a fair amount of food-making: Chex party mix, pecans, frosted cookies. Things that could be chores—writing our part of the family Christmas letter, wrapping presents for distant relatives—were transformed into events through the magic of the Twenty-Four Days concept.

Rebecca Onion

One of the best activities my parents came up with was the individual shopping trip. Mom would take one of the three of us out solo, while the other two stayed home to have dinner with Dad. The shoppers would get dinner at Friendly’s (chicken tenders, in a booth). We’d go through the absent siblings’ lists, talking about what we thought they’d most enjoy receiving and thinking a little about whether their requests fit into the parental Christmas budget. Then we’d go to a few nearby malls (this was before internet commerce, when Zayre’s was still a going concern) and pick out presents. We’d get home late, feeling special, with the station wagon full of surprises we’d help Mom smuggle in past our siblings, singing “Christmas is coming/ The goose is getting fat” when they grew too curious.

Thinking back on our Twenty-Four Days tradition, I think it must have gone a long way to help Mom manage the pace of the month, which could have been made way worse by her demanding, Christmas-mad offspring. Reading the L’Engle book again, I was struck by how much Vicky expects from her own very pregnant mother. Vicky wants nothing more than for the baby to stay put, so that her mother can be home for Christmas and doing everything she usually does to make the days around it special for her children. Fretting over what Christmas would be like if her mother happens to be in the hospital for the big day, Vicky mourns: “Who would make Christmas dinner? Make the stuffing? Roast the turkey? Fix the cranberry sauce? What about putting out cocoa and cookies for Santa Claus the very last thing on Christmas Eve? What about—what about—everything?” It turns out that Mrs. Austin has already made all of the food (at eight months pregnant!) and frozen it, so that her husband can put it in the oven if she’s away on the holiday itself. (Remember: 1964.) Christmas can be hard on mothers.

The Twenty-Four Days tradition let my own mom think ahead about what needed to get done so she could then enlist all of us in the work of the season. By distributing Christmas across three weeks and change, she could let us know what to expect, managing our wild excitement while also making sure everything was accomplished. Don’t get me wrong: The Twenty-Four Days concept didn’t make Christmas stress-free for a working mom of three. But it must have helped, and it certainly made the season brighter, longer.