My 3-year-old son, for reasons that can only be guessed at, has an abiding fascination with bad guys. He’s deeply enamored of the Star Wars films, for instance, but it’s primarily the dark side of the Force that he’s drawn to. When he dresses up it tends to be in the dramatic apparel of intergalactic villainy: a Darth Vader, a Kylo Ren, an Imperial Stormtrooper. He has, too, a fondness for films whose protagonists are, on paper, obvious villains, but whose nefariousness is mitigated by the influence of children. He’s a big fan, as such, of the Despicable Me films, and of Hotel Transylvania and its sequel, in which Adam Sandler’s crotchety but basically good-natured Dracula does not murder people and suck their blood but instead deals with a comic variety of domestic upheavals, like an undead Clark Griswold.

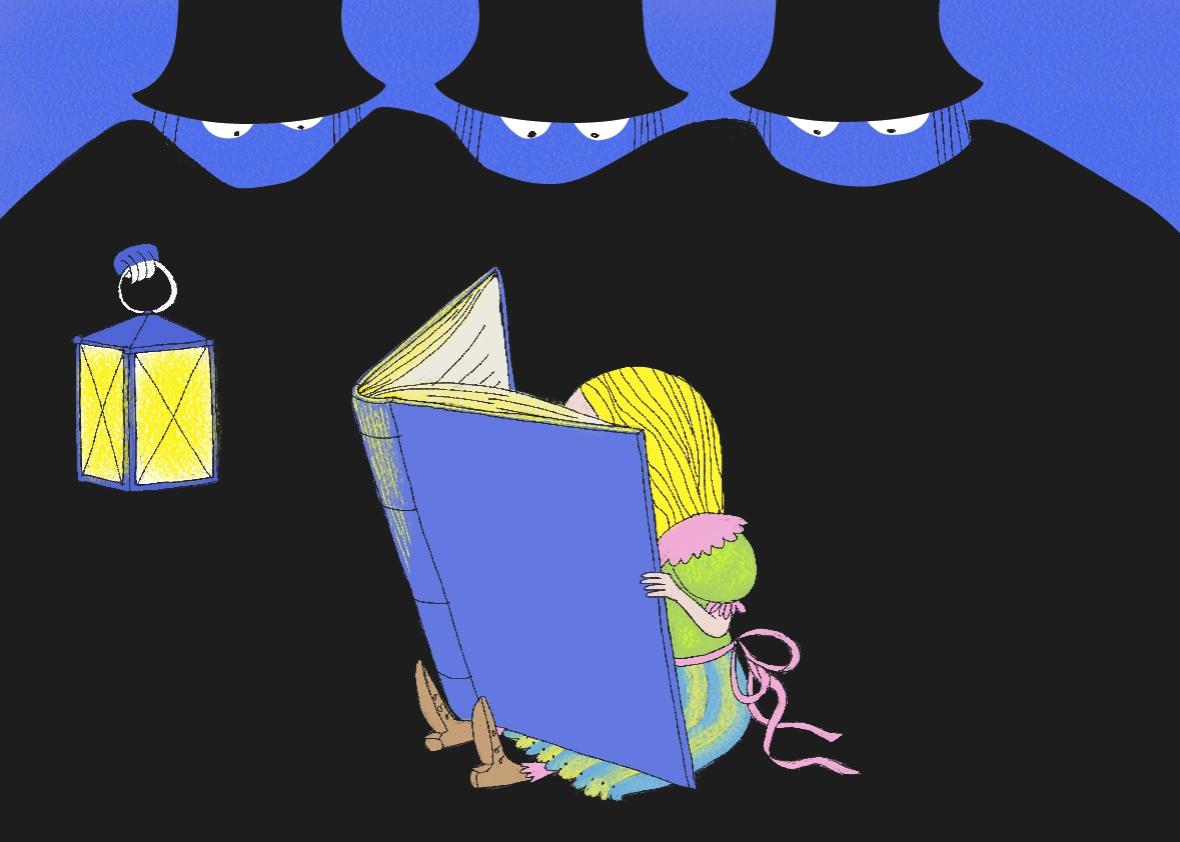

A few months back, he and I were in the children’s section of a bookstore, enacting our customary routine of proposal and rejection. He had dismissed out of hand a dozen or so of the titles I’d taken off the shelf and presented for his inspection—salutary tales, mostly, about anthropomorphic beasts progressing toward the state of virtuous sleep—when I came across a book with an attractively enigmatic cover featuring three elegantly rendered figures, dark-cloaked and glowering outward at the prospective reader from under tall black hats. It was, I noted, published by the art book publisher Phaidon, and it looked fancy. I was already imagining the memories he would have of the book in 30 years’ time: the images, the feel of it in his hands, the smell of its pages.

“This one is interesting,” I said. “Shall we take a look?”

We flicked through the beautifully illustrated pages. There were highway robberies, carriage wheels smashed with axes, horses blinded with pepper. There were scenes of terror and chaos, and conspicuous blunderbuss usage. My son nodded in forceful affirmation.

“We get this one,” he said. “The robbers one.”

We’ve read this book—which is called The Three Robbers, and is the work of the French illustrator and author Tomi Ungerer—on quite a few occasions since then. It gets a disproportionate amount of airtime, on those evenings when I put him to bed, because his mother flatly refuses to read it to him.

My son handed it to her one evening as he climbed into his bed.

“Mama doesn’t read that book,” she said. “Only Dada reads that one. If you want that book, Dada can put you to bed.”

My son flung the book to the floor with what seemed to me an unnecessarily extravagant flourish, and choose instead a book about an obstreperous dog named Fred who won’t sleep in his own bed. (He likes The Three Robbers, and he likes me too, but not nearly as much as he likes his mother.)

“I don’t know about that Three Robbers book,” she said to me later. “It’s unnerving. I don’t know what the moral of it is, but I don’t know if it’s necessarily a good one.”

It was, I agreed, unnerving. But the moral ambiguity was what I liked about it, I said, though as I spoke I was uncomfortably aware that the standards of literary taste were not necessarily coterminous with the standards of good parenting.

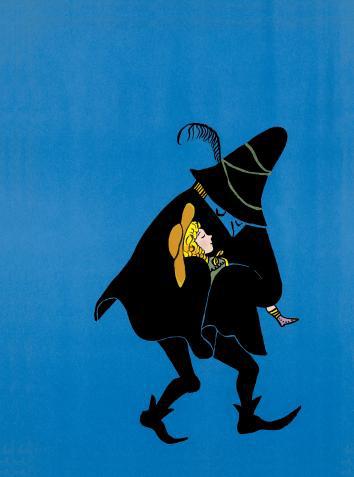

Whatever designs The Three Robbers has on the child who encounters it are not those of a typical children’s book. It tells the story of the three above-mentioned cloaked and hatted robbers, who stalk the roads of an unnamed land “searching for victims.” Above this kingdom of easy quarry, after long nights of threatening and plundering and blinding horses with impunity, they hide out in a cave stacked high with treasure chests of loot. One night, the robbers intercept a carriage that is carrying only one passenger, an orphan girl named Tiffany who happens to be on her way to live with a wicked aunt, and who therefore welcomes as a reprieve the appearance of these shadowy figures. We are told, with eerie simplicity, that “since there was no treasure but Tiffany, the thieves bundled her in a warm cape, and carried her away.” (Ungerer’s illustration is disconcerting: One of the robbers hauls off a gold-ringleted Tiffany, who is apparently sleeping peacefully. The robber’s eyes are closed, too, as though bearing her off into some kingdom of dreams.)

Phaidon

When Tiffany awakens the next morning, she discovers the vast stockpile of treasures in the robbers’ cave, and asks them the best possible question to ask of accumulated wealth: “What is all this for?”

They’re not sure, it turns out; they seem to be pulling off heists purely for the love of the game. Under the influence of Tiffany, the robbers then pivot their whole business model toward philanthropy, and set off to “gather up all the lost, unhappy, and abandoned children” they can find, buying a beautiful castle for all the children to live in. In one of the book’s last images, the robbers oversee a phalanx of these gathered-up foundlings as they file happily into the castle, all dressed in blood-red cloaks and hats styled identically to the robbers’ black clothing. The book ends on a cheerful note: As the orphans grow up and have children of their own, a settlement of red-uniformed villagers eventually forms around the castle. “These people people built three tall, high-roofed towers. One for each of the three robbers.” The final image is of this village, lit by a full moon, its three towers echoing the silent presence of the robbers themselves.

It’s a happy ending, in its way, but one that is all the more ambiguous for its cheerfulness. There is no comeuppance, no catharsis, no moral resolution of any sort. My wife’s unease about the book is not easily assuaged, nor, I suppose, is my own. The book generates a lot of questions, not the least of which is the question of what is actually going on. Since when is kidnapping children OK, even if they’re on their way to live with a wicked aunt? Are we to view these robbers, who only a few pages back were smashing carriage wheels with giant red axes and aiming blunderbusses at the faces of the bourgeoisie, as suitable caregivers for an entire village of lost children? What’s with the red uniforms—are we dealing with some kind of cult here? Why does Tiffany, having initially been presented as a likely candidate for protagonist, disappear entirely in the final third of the book? And perhaps above all, why do we never see the robbers’ faces? Why in the book’s final image are they transformed into three looming towers, even more blank and mysterious in their last appearance than in their first?

To be troubled in this way, to be bedeviled by ambiguities, is the hallmark of an encounter with a work of art. And this is what sets The Three Robbers apart from any of the other picture books I have so far read to my son. It isn’t that some of those other books aren’t legitimate art in their own right; it’s that there is something of the actual world—the uncanny murk of lived reality—in the volatile fantasy of Ungerer’s story. He seems to take an almost malicious pleasure in denying you, the parent, the possibility of any straightforward moral decoding of his work.

“They’re good guys and bad guys at the same time,” my son put it one evening, a remark that seemed to me to be about as much as could be said of most non-imaginary people, including both of us. I leaned back into the large stuffed elephant I placed against my son’s headboard, settling in for a little light textual analysis.

“So maybe,” I said, “there’s no such thing as good guys or bad guys.”

He turned to me with a look of keen skepticism.

“Maybe,” I said, “there’s only doing good things and doing bad things. So the robbers are good guys when they do good things, and bad guys when they do bad things.”

“Are bad guys not real?” he said.

“I mean, sort of,” I said. I was in over my head here; I had, I realized, no idea what lesson, if any, I was trying to impart. “If you do bad things,” I said, “that makes you a bad guy.”

“So bad guys are real.”

“No, yeah, you’re right,” I said, grateful for a route out of this moral relativist quagmire I’d dragged us into. “They are definitely real.”

For what it’s worth, I completely understand and sympathize with my son’s preference for being put to bed by his mother.

* * *

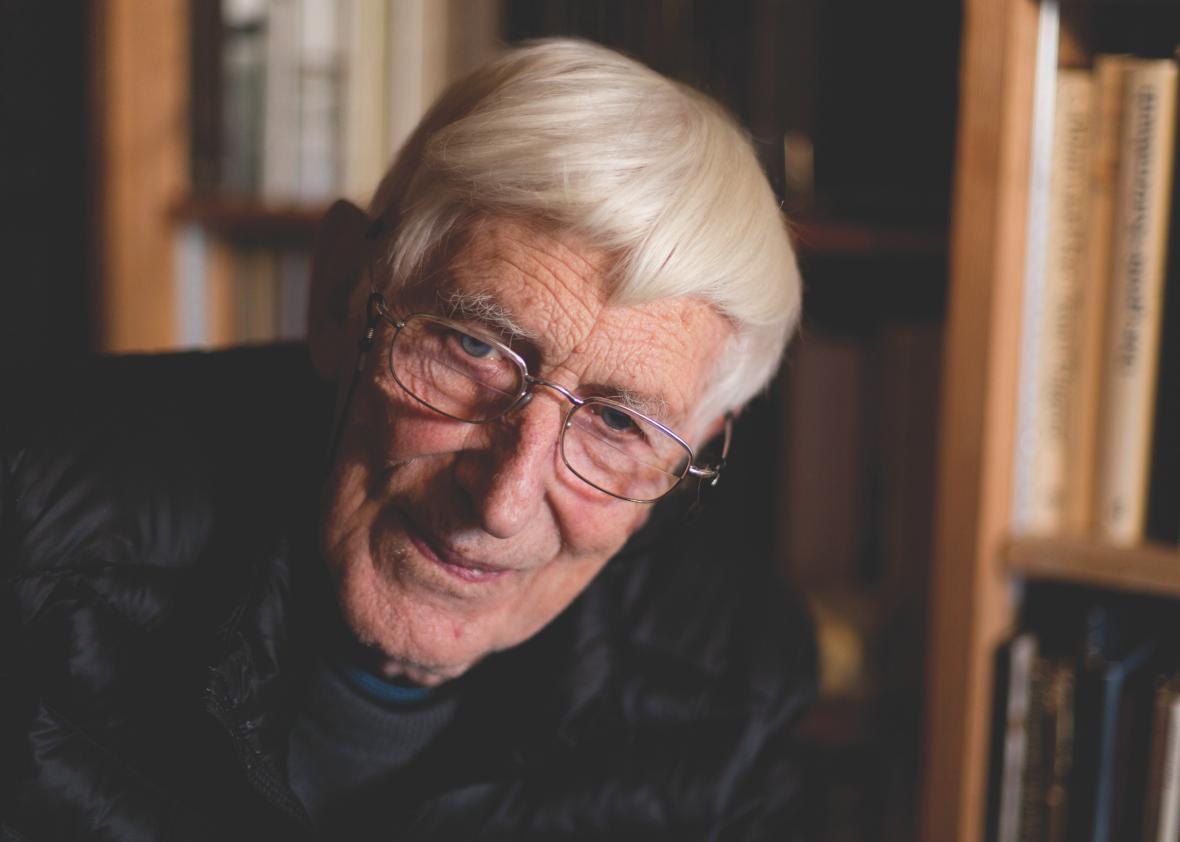

This moral ambiguity is Ungerer’s stock in trade as an artist, and is part of what makes him such an extraordinary figure among children’s writers. Now in his mid-80s, he was born in Strasbourg and grew up during the German occupation of Alsace. In the 2012 documentary Far Out Isn’t Far Enough: The Tomi Ungerer Story, he says that the major formative influence over his illustrative style was Adolf Hitler; he internalized early on what he calls the “punch in the face” aesthetic of Nazi propaganda. Ungerer, who lived in the U.S. from the 1950s to the late ‘70s, is almost as famous for his viscerally effective anti–Vietnam War posters as he is for his children’s books. A parallel vocation as a purveyor of illustrated erotica––his unsettling satirical renderings of the mechanization of human sexuality—eventually damaged his primary career; he became something of a pariah in the world of American children’s publishing, a situation that lasted up until his recent career rehabilitation. (To be clear, this rehabilitation has not led to any kind of ubiquity on the bookshelves of the world’s small children. The fact that the major force behind this career revival—the publisher releasing an Ungerer treasury in October—is Phaidon, publisher of books about Cindy Sherman and Robert Mapplethorpe and Paul McCarthy, suggests Ungerer is unlikely to steal the Guess How Much I Love You guy’s lunch money.)

Herman Baily

Ungerer returns repeatedly in the documentary to his conviction that children should be introduced, through art, to the darkness and complexity of the world. “Just like in my book The Three Robbers,” he says, “what fascinates me is that no-man’s-land between the good and the bad. You know, a no-man’s-land is not a place where you should kill each other, but a place where you can meet; and I think the good can learn a lot from the bad, and the bad can learn a lot from the good. Why shouldn’t they have a bit of fun with each other? Excuse me, that’s what life is about.”

This no man’s land is fertile territory for art, but it’s a place where most of us are reluctant to bring young children. When books for this age group do have baddies as protagonists, the narrative tends to hinge very firmly on moral requital. Take, for instance, Julia Donaldson’s entertaining but right-minded The Highway Rat, in which the titular rodent marauder, whose racket involves stealing at sword-point the food of other animals, gets trapped in a cave by a clever duck and winds up working as a janitor in a cake shop, thereby providing closure to a moral psychodrama of sin, punishment, and redemption. (Even Finn, the Stormtrooper at the center of The Force Awakens, is immediately revealed to be a good guy who rebels against the Empire.) Ungerer’s highwaymen, by contrast, are never brought to justice, and the form of their rehabilitation is arguably more unsettling than the sins of which they are being redeemed.

Like all the best artists, Ungerer has no interest in imparting moral lessons; he has no interest in giving children—or, more accurately, their parents—a comforting view of life. He’s interested in illustrating how things are with people, how things are with the world. I don’t know how comfortable I am with this as a parent, but my son seems perfectly delighted with it.