Nightlight is Slate’s pop-up blog about children’s books, running for the month of August. Read about it here.

Since the original Nancy Drew series was introduced in 1930, the girl detective has evolved from squeaky-clean teen to college coed to, most recently, a thirtysomething police officer in a pilot CBS reportedly nixed as “too female” for its fall schedule. Though Carolyn Keene is the name that appears on the cover of every Nancy Drew book, it’s no big secret that the books were written by ghostwriters, as were many popular kids’ megaseries of the past, from Sweet Valley High to the Baby-Sitters Club. To try to find out what it’s really like in the ghostwriting salt mines—and how the Nancy Drew character has evolved for a more feminist era—we talked to former ghostwriter Alice Leonhardt. Leonhardt was a ghostwriter for various kids’ mystery series, including Nancy Drew, for several decades beginning in the late ’80s. Lately, she’s mostly been teaching and busying herself with writing her own books—including, most recently, the Dog Chronicles, for Peachtree Publishers. Slate chatted with Leonhardt about the art of ghostwriting and the evolution of Nancy Drew.

How did you wind up becoming a ghostwriter?

I started writing for the Linda Craig series. That was because I had a horse background. It’s a very horse-y series. It was based on an older series, maybe from the ’50s, [but] they resurrected it in the ’80s. They were mysteries set around horses. I wrote quite a few of those. The Hardy Boys and all those—Nurse … ? What was the nurse’s name? I don’t even remember. There were so many series out from Stratemeyer [the company that created Nancy Drew]. … But anyway, that was the first series I worked with.

I guess editors were putting out feelers for people who could write horse stuff.

What’s the difference between that as an exercise and writing your own books?

[With] the Nancy Drews, you were given a Bible: Here are the characters, here are the books that came before. But you had to create your own plot and story and synopsis and submit that, and then you had to create your own outline. So it was pretty much writing a book; you just had to use somebody else’s stock characters. And of course after reading two or three of the books, you could pretty much get an idea of characters and how they acted and how the setup for the books went. Even the Linda Craigs always had a cliffhanger at the end of the chapter, and the chapters were so long, so there was a structure, but the creativeness within that structure was yours.

So what was the process like when you were writing for Nancy Drew? Was it easy to get your outlines and synopses approved?

Generally after the first book or two, the editors and I would just talk on the phone: “This is my idea; what do you think?” And they knew all the books that had come or the ones that were in production. They’d be able to say, “Well, that’s too similar to X, or we already did that in Y.” With Nancy Drew, you had Nancy Drews, you had the Hardys, you had the Nancy Drew Case Files, you had the Digests, you had the Super Mysteries, so there was a lot of overlap. The editor had to keep all the different plots straight, what was going on in which book.

You mentioned a Bible that ghostwriters had to consult. How detailed was it?

It gave you the characters; it gave you the setting. Mostly it was just a very brief synopsis of the books that had been published before so that you had an idea what had already been done.

Did you have any relationship with Nancy Drew or any of the series from your own childhood?

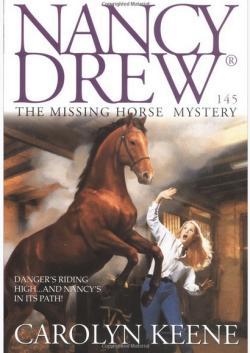

Amazon

No. Everything was horses—that’s all I read was horse books. A lot of the Nancy Drews I later wrote were very, very horse-oriented.

The editors and packagers didn’t mind that you weren’t a Nancy Drew expert?

They were just desperately looking for decent writers. They were cranking these out one a month maybe, with the Nancy Drews. They had incredible schedules to meet. So they were looking for decent writers who could write mysteries, which isn’t all that easy, because a lot of the books that I revised and edited for them were pretty terrible.

Do you have a sense of how successful the books you ghostwrote were?

When you are writing for a flat fee—I wrote for the Thoroughbred series as well, and you’d get like a 1 percent royalty, but believe me, you never saw the royalty—when you write for a flat fee, that’s it. You send in the book, and you never hear about it again. It’s totally different than when you write your own book and you’re publicizing and you’re talking about it and you’re checking the statistics.

The series really was an entity of its own. Individual books didn’t do well; the series did well. It wasn’t your books that propelled the series to stardom; it was how well the series was received by the kids reading it and librarians and yadda yadda.

Was it hard to write things like personality for these characters you hadn’t created?

A good writer can read a couple of the Nancy Drews and say, “Oh, this is Bess, and this is George, and this is Nancy,” but you want to make them real people. It was so plot-heavy. Of course Nancy, Bess, and George all had different characteristics, but the stories revolved around the plot.

Did you have any instructions about modernizing the books or making Nancy Drew appeal to a new generation of kids in an increasingly feminist era?

No, again, you read a couple of the books. We didn’t use the word roadster anymore. The books from the ’50s were kind of stilted. But all of them revolved around adventures, so you could propel the story forward with adventures. They were set in modern times. One of the Nancy Drews I did was in a theme park, like Busch Gardens, so of course that was different than it would have been in the ’30s and the ’40s.

How long did each book take you?

You had deadlines. You didn’t have much choice but to meet the deadlines. Some of them were rushed. Sometimes people would drop out of a project and it would be, “I need this in six weeks.” And sometimes you had more time.

Why did you stop ghostwriting?

Part of it was I got too busy with my own books that were very research-heavy.

The pay was just OK. Since you weren’t getting royalties, if I could write a book where I was getting royalties, that’s what I had to choose.

Have you continued reading the Nancy Drew series since you stopped writing for it?

No. … I don’t do a lot of publicity anymore. You just get to a point in your career where you burn out from the intense amount of marketing and signings and blogging and interviewing and going to school visits and going to conferences.

You evolve as a writer. I started back to teaching again. I’m into antiques.