They called her ACM, but never, ever, to her face. Her staff at the celebrated Room 105 of the New York Public Library were expected to observe strict decorum at all times, but those who passed muster got to see the giants of the first age of children’s book publishing walk through the door to pay court to Anne Carroll Moore, superintendent of the Department of Work With Children for the NYPL from 1906 to 1941. Beatrix Potter considered her a close friend; she could summon William Butler Yeats to appear at her library events. Carl Sandburg described Moore as “an occurrence, a phenomenon, an apparition not often risen and seen among the marching manikins of human progress.”

The first half of the 20th century was a formative era for the relatively new enterprises of children’s libraries and children’s book publishing, and Moore was one of its undisputed doyennes, if not quite its absolute ruler. Authors, editors, and publishers sought audiences with Moore for advice and, above all, for her blessing on their latest offerings. In addition to presiding, unofficially, over children’s librarianship across the nation, Moore wrote a regular column reviewing new books for the New York Herald Tribune and, later, the Horn Book, a highly influential journal devoted to children’s literature, co-founded by one of her many protégés. Her end-of-year lists were sacred anointments of the chosen titles; she was reputed to be able to make or break a book, much as the New York Times’ theater critic was said to determine the fate of a new play. The only thing more terrible than having your book dismissed by Moore with her signature opprobrium—“Truck!”—was the rubber stamp she kept in her desk that read “Not Recommended for Purchase by Expert.”

Outside of library circles, Moore may be best known today as the lady who insisted that publishing Stuart Little would ruin E.B. White’s reputation. As recounted by Jill Lepore in the New Yorker, Moore—who despite her retirement from the NYPL remained a figure of formidable influence until her death in 1961—had cajoled White for years to finish the children’s book he’d been working on. Like many people who make their profession in the support of books and reading, Moore felt a proprietary pride in the titles she championed and wasn’t shy about taking credit for the success of her favorites.

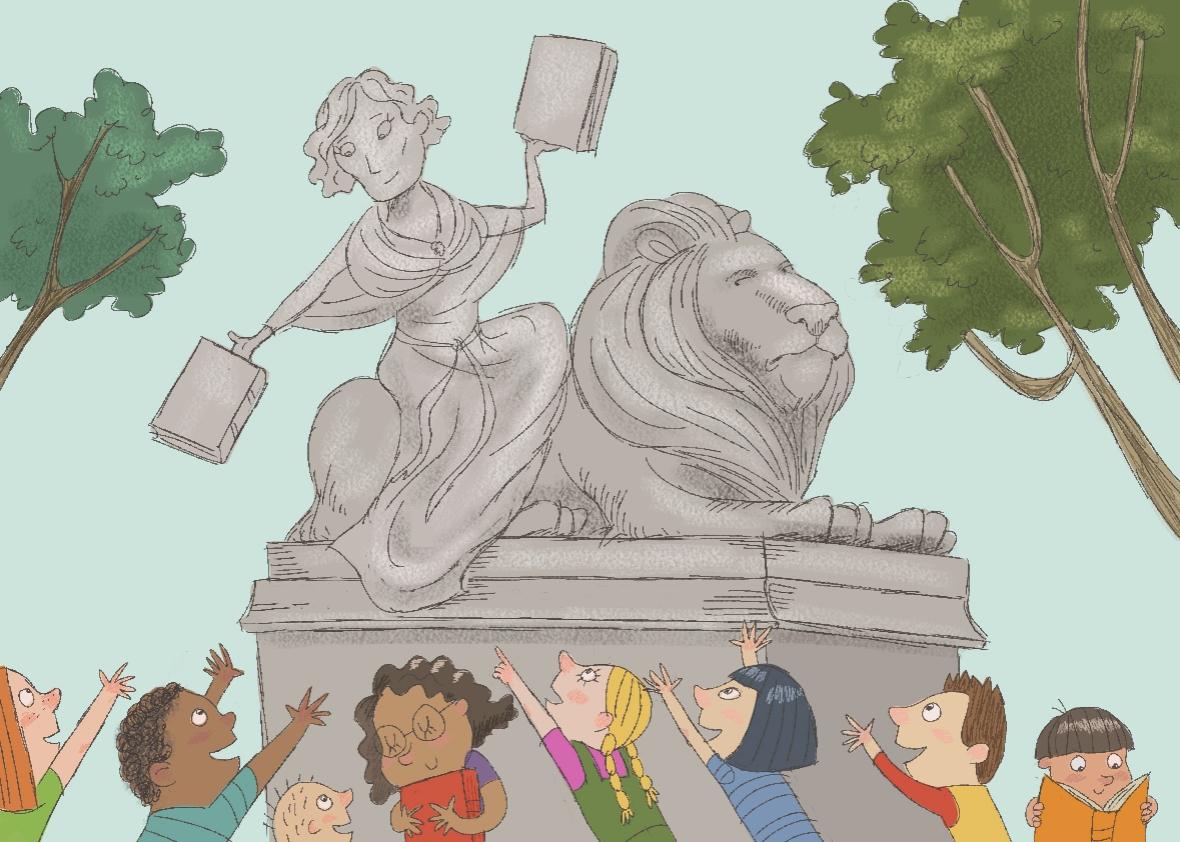

New York Public Library

But she hated Stuart Little from the moment she read an advance copy in her residence at the Grosvenor Hotel on Fifth Avenue. Her reasons for this are not entirely clear; White and his wife, Katharine, fiction editor for the New Yorker, threw out the 14-page letter in which Moore detailed her objections. But Moore’s own notes indicate that she felt White had made a fatal error in muddling the realistic and the fantastic in such a way that child readers might be confused. As White recalled it, “She said something about its having been written by a sick mind,” and that it would be “bad for children”—but then, authors are notorious exaggerators when it comes to characterizing their bad reviews.

White’s book thrived despite Moore’s lobbying to keep the NYPL from purchasing copies and to keep Stuart Little off the nominating lists of the major library prizes. In this tale, Moore represents the fuddy-duddy old guard in opposition to a new (and notably New Yorker–ish) generation of authors and publishers. The new wave was personified by White’s friend and editor for Stuart Little and, later, Charlotte’s Web, Ursula K. Nordstrom. Nordstrom, 40 years Moore’s junior, would go on to become a legend in her own right by publishing Harriet the Spy, Harold and the Purple Crayon, Where the Wild Things Are, and Where the Sidewalk Ends, some of them, perhaps, also not the sort of books Moore would find perfectly suitable to recommend purchasing.

It all depends on your perspective, however. Move the slider of history back 30 years and Moore was a revolutionary. Until the late 19th century, libraries weren’t even considered a fitting place for children under 10, and the first children’s rooms, installed in the 1890s, were initially meant to cordon off noisy young patrons so they didn’t bother the adults. Moore pioneered the children’s room as we still know it today: a homey space with plenty of comfortable, child-size chairs, art on the walls, space for events like storytelling, which Moore almost singlehandedly made a regular feature at libraries. All children’s librarians adopted her credo of the Four Respects: respect for children, respect for children’s books, respect for one’s colleagues, and respect for the children’s librarianship as a profession. None of these was a given before Moore and her cohort came along.

Two excellent books published a few years ago, Minders of Make-Believe by Leonard Marcus and Bookwomen by Jacalyn Eddy, recount how a group of formidable women, of which Moore was one of the leading lights, essentially created and ran the children’s book industry in the early and mid-20th century. In libraries, but most especially in book publishing, children’s departments were the only divisions where women could rise to positions of authority. Those offices became havens for ambitious women who loved books, but they were also genteel ghettos of a sort. “I suppose that’s a subject on which a woman might be supposed to know something,” said the head of Macmillan to Louise Seaman Bechtel, who ran the first dedicated children’s book department at a major American publisher.

Moore’s pet cause was the improvement of children’s literature itself. Apart from the occasional great title produced as a one-shot by a talented author whose main interests lay elsewhere (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Just So Stories), she rightly regarded much of what was then being published as “mediocre” and poorly produced. Moore surveyed the field and found it “strewn with patronage and propaganda, moralizing self-sufficiency and sham efficiency, mock heroics and cheap optimism.” Librarians as a whole rejected series fiction like Horatio Alger’s paeans to rags-to-riches American individualism or, later, the Nancy Drew, Bobbsey Twins, or Hardy Boys books. They hated the flimsy paper and binding, material evidence of the contempt publishers felt for their young readers.

Today, more quality children’s books are published every month than any one child can read, and if kids occasionally take a ride with Nancy Drew in her blue roadster, most adults see nothing to complain about. But Moore articulated her Four Respects for a reason; in her day, children were regarded by publishers as indiscriminate readers easily satisfied by mass-produced pablum. Good kids’ books were hard to come by. Worst of all, in Moore’s eyes, was the “poverty” of decent books for girls. Raised in a small town in Maine where she spent much of her time outdoors and aspired to follow in the professional footsteps of her attorney father, Moore had no patience for the “moralizing and didactic.” A girl, she wrote, “cannot afford to waste her emotions nor her time. She has need of every resource that may fortify her spirit, sharpen her native wit and challenge the full powers of mind and heart.”

Moore—unlike most of the sisterhood that ran the children’s book world in her day—wasn’t a product of a Seven Sisters college; she had accompanied her father on visits to his poor and immigrant millworker clients. That could explain why, as Eddy notes in Bookwomen, Moore’s department at the NYPL was strikingly diverse compared with the rest of the institution: “Moore selected new staff,” Eddy writes, “on the basis of her intuitive responses to applicants, rather than race or ethnic background.” She hired the NYPL’s first Puerto Rican librarian. (She also found one of her most successful recruits, an exiled White Russian who had attended balls at the imperial court, in the dress department at Lord and Taylor.)

Margaret K. McElderry, a prominent editor and another of Moore’s protégées, wrote of how much she learned as a young librarian when she was assigned to the Harlem branch library at 135th Street and Lenox, where she was the only white staff member. Moore saw to it that every branch library in New York City had a children’s reading collection, books that couldn’t be checked out but were freely available to be read on site, and she dictated that each collection should be tailored to the specific needs and interests of its neighborhood. McElderry wrote of how different these books were from any she’d seen before: “The pages felt thick somehow, and pulpy, and they were almost grey in color, not from abuse, but from the many, many hands that had held them and turned the pages.”

Without a doubt, Moore had her peculiarities. She kept a wooden puppet named Nathaniel on her desk and took it with her when speaking to groups of children. (Sometimes she made it talk to her adult visitors, as well.) She could be high-handed and intimidating. In her later years, she remained fixed to positions she’d adopted in her heyday, rooted in conflicts that had long since expired. Part of her objection to the integration of fantasy and realism in Stuart Little, for example, might have derived from the schism between children’s librarians like Moore, who favored fairy tales and other “timeless” and archetypal narratives, and educators like Lucy Sprague Mitchell, founder of the Bank Street College of Education, who believed that children should be given books with contemporary settings depicting relatable situations and problems.

It can’t be easy to leave the job that has been your mission and the center of your life. As Horn Book critic Barbara Bader bluntly puts it, Moore “lived too long, and too much enjoyed playing the role of quirky despot, for the good of her reputation as primal force.” But she was that force and changed the world of children’s books for the immeasurable better. She deserves to be remembered for that, and not just for her aversion to certain nattily dressed mouse.