At the moment, Republicans still insist that they want to pass a tax reform bill by the end of the year. Not just a tax cut, mind you, but a full-fledged reform package that will clear out the countless deductions, loopholes, and special-interest carve-outs that have turned our corporate tax code into a sieve.

In theory, this is a completely unobjectionable goal. The United States could use a more rational tax system that leaves businesses on more even footing with one another, regardless of how many pricey lawyers and accountants they hire. Unfortunately, it’s not clear the GOP’s plans will move the country in that direction. In some respects, it could make the problems with our current tax code even worse.

Republicans often complain that the United States has the rich world’s highest corporate tax rate, topping out at 35 percent, which they argue drives business investment and jobs overseas. But that figure is largely an illusion, thanks to the vast array of deductions that companies can claim and the ability of multinationals to shelter their profits offshore. Analysts typically find that, when all is said and done, U.S. corporations pay an average rate somewhere between 22 and 29 percent, which, depending on whose estimates you rely on, may or may not be in line with our peer nations.

The fact that few companies actually pay the top corporate rate isn’t something to celebrate, however. It’s a sign that our tax code is a bit of a farce. The joke gets worse once you look at how tax rates vary across businesses and industries.

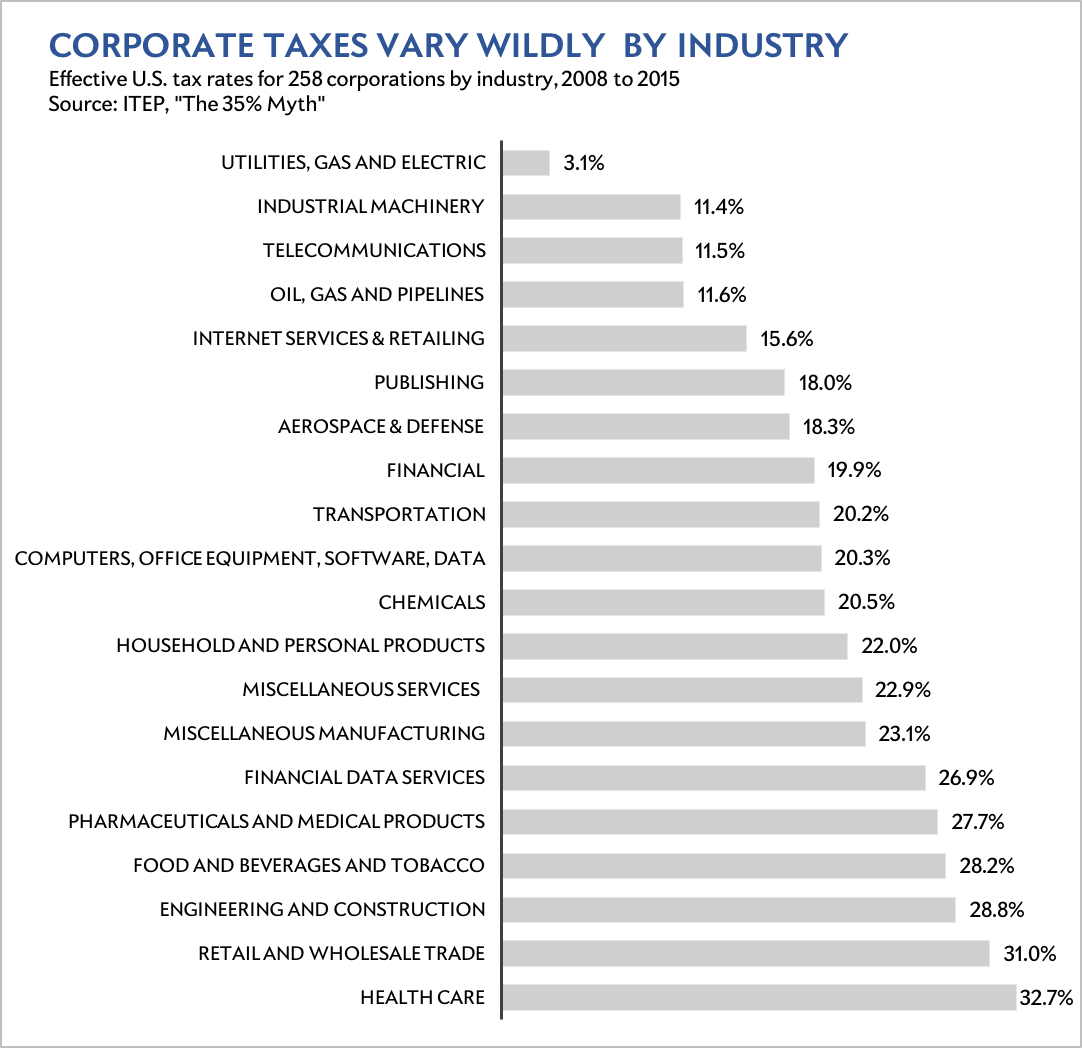

Earlier this year, the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy released a report in which it analyzed the tax rates paid by members of the Fortune 500 between 2008 and 2015. The authors selected the 258 corporations that were profitable in all eight years to avoid dragging down the average with companies that paid no taxes because they lost money. They found 100 different companies that, despite being consistently profitable, paid zero federal taxes in at least one year, and 18 that paid no taxes in any of the years surveyed. Meanwhile, there were vast differences in average rates between industry. Utility companies paid an average rate of just 3.1 percent; tech companies paid about 20 percent; retailers and wholesalers paid more than 30 percent, as did health care providers.

ITEP

A good tax code doesn’t have to treat every single industry identically. Nobody but a lobbyist, however, would purposely design one in which some kinds of businesses consistently hand over a third of their profits to the IRS while others pay next to nothing. And in case you’re skeptical about the findings of a liberal think tank, the U.S. Treasury Department found similar, if slightly less pronounced, disparities when it ran its own analysis on the taxes paid by all profitable corporations with more than $10 million in assets.

It can be hard to pinpoint how specific companies minimize their tax bills, because corporations aren’t required to disclose the nitty-gritty of their returns. But ITEP notes a few broad issues. Multinationals are able to park profits in offshore tax havens. This disproportionately benefits large tech firms that earn profits from their intellectual property, since it’s relatively easy for them to shift profits overseas. Meanwhile, companies that regularly make large capital investments in machinery and other equipment benefit from rules that let them quickly write off the cost of those purchases. Its not a coincidence that most of the companies ITEP found that paid nothing in federal taxes over all eight years were utilities, which are typically required to make major upgrades each year.

Because Republicans don’t have an official tax plan yet, it’s impossible to say how many holes in the tax code they’ll try to plug. But the indicators so far aren’t promising. House Republicans have identified some deductions they want to repeal, which are worth about $171 billion over their first 10 years—not a great deal in the scheme of a corporate tax that’s expected to bring in more than $400 billion this year alone. On the big-picture issues, they seem intent on wrenching even bigger gaps in the tax code. Take the issue of tax havens. Right now, the GOP seems intent on moving the U.S. to what’s known as a territorial system, where the government wouldn’t tax corporations at all on profits earned abroad. This will of course eliminate the need for companies to stash profits in Ireland and the Cayman Islands. But if anything, that will only encourage companies to make like Apple and use accounting gimmicks to shift their U.S. profits overseas. It’s like trying to fight shoplifting by making it legal.

Or, consider the advantages those utilities seemingly enjoy. Right now, many Republicans want to make it possible for companies to write off major capital investments even faster by moving to a system of immediate expensing. There may be some economic reasons to favor that idea—it could possibly lead to a bump in corporate investment—but it essentially doubles down on the system that now lets some companies shield their profits from taxes entirely.

“I think it’s fair to say that the Trump plan as we understand it would actually increase the gap between the haves and the have-nots,” ITEP’s Matthew Gardner told me. “It would accentuate the preferential treatment that certain sectors of the business world and certain high-income Americans get.”

There is at least one way Republicans are trying to even out the corporate tax code. As of now, they’re talking about lowering the top rate by 10 or 15 percentage points. That will at least ensure that companies on the high end of the tax spectrum will pay a bit less. But that’s not really a tax reform. It’s a plain old cut.