Chances are you haven’t thought much lately about the economic tragedy that’s unfolding in Puerto Rico. Not with nukes in North Korea and neo-Nazis and Obamacare repeal to dwell on. But Thursday at the New York Times, Mark Weisbrot of the Center for Economic and Policy Research has written a grim reminder that, in the wake of the island’s debt crisis, we’ve essentially sentenced it to another decade of austerity-fueled economic depression.

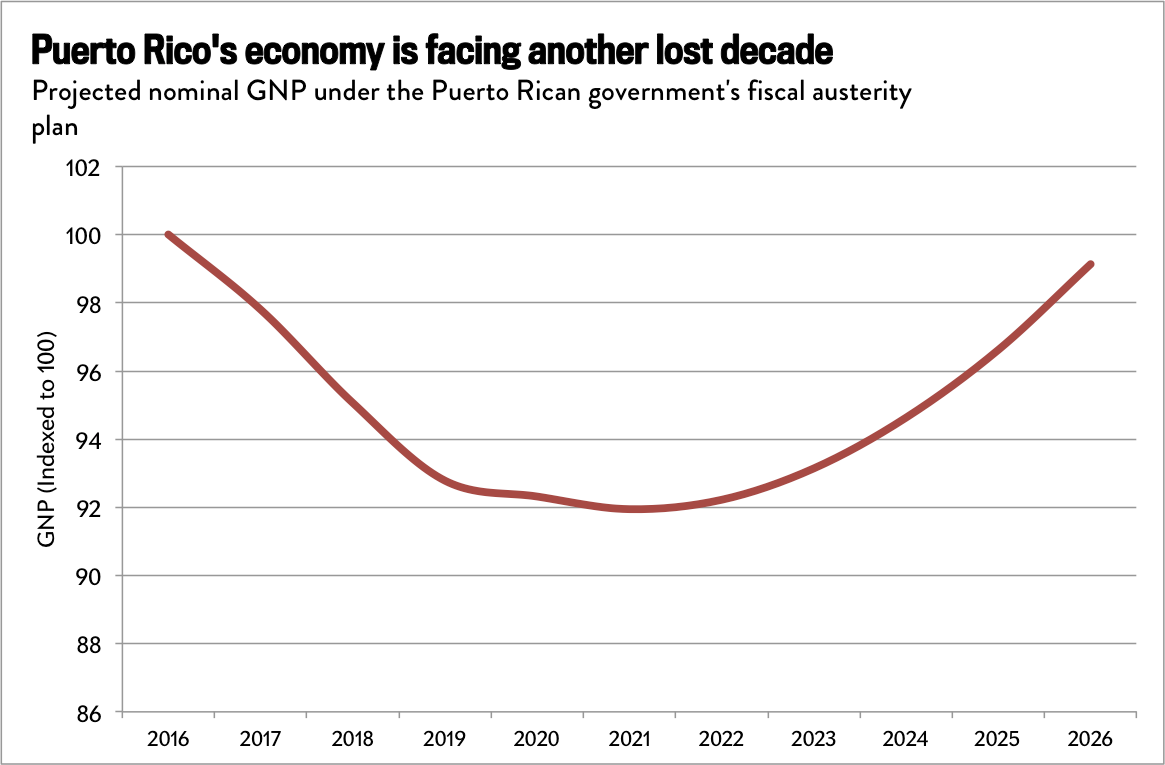

Puerto Rico has been in a recession more or less continuously since 2007, which helped force it into an unsustainable spiral of borrowing that ended in default last year. Congress responded to the growing crisis by passing PROMESA, an act that placed the territory under the oversight of a bipartisan financial control board. This March, that panel finally approved a fiscal repair plan meant to close Puerto Rico’s budget deficit while setting aside some money for bondholders. There’s an upsetting assumption behind this road map: that it will face another full 10 years of stagnation. As this graph from the plan shows, the territory’s economy isn’t expected to start growing again until 2022.

Even then, the island’s economy will still be smaller in 2026 than it is today, even before accounting for inflation.

Jordan Weissmann/Slate

And that’s probably too optimistic. As Weisbrot writes, the plan doesn’t factor in the effects of austerity, “which would add more years of decline.” More generally, these sorts of debt-sustainability projections are notoriously too sanguine about the ability of governments to keep paying their creditors while absorbing deep budget cuts. We’ve seen this show play out repeatedly in Greece, where international technocrats spent years making fanciful projections about how the country could slash its spending, raise taxes, gradually bounce back from a depression, and somehow make good on its (reduced) debts. The difference is that, as John Jay College economics professor J.W. Mason notes, Puerto Rico is just now entering into an austerity plan after already experiencing an employment collapse similar to Greece’s. And if you take the official projections seriously, Puerto Rico’s economy—measured by gross national product—should reach Greece’s recent nadir within the next few years.

Europe’s austerity politics have reduced Greece to a perpetual economic crisis. We’re handing Puerto Rico the same prescription, and bizarrely expecting different results.