Thinkstock/FooTToo

For a few years following the recession, there was some speculation that America had reached peak driving. Possible reasons for this epochal shift included reurbanization, telecommuting, and the stall of southbound migration patterns (we like our towns denser up north).

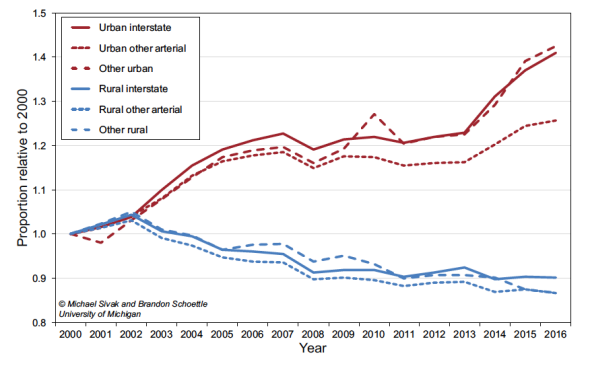

It now appears the shift was a blip. The past three years have all but erased a 10-year decline in driving that began in 2004; in both 2015 and 2016, vehicle miles traveled, or VMT, per capita rose by more than 2 percent, a higher rate than at any time in the past quarter-century.

Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle/The University of Michigan Sustainable Worldwide Transportation

Basically, we’re driving as much (per person) as we were in 2000, and the rate is rising. But a meaningful, long-term shift is occurring in driving patterns, as a new paper by Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle of the University of Michigan makes clear. Urban driving is up 33 percent in that time; rural driving has fallen 12 percent.

That enormous divergence can’t be explained by the country’s ongoing urbanization and population growth. America’s cities (by which I mean, mostly, their sprawling exurbs) have grown by 19 percent in that time—meaning that bigger cities account for just 58 percent of the urban driving mileage increase. Rural areas, meanwhile, have seen their distance driven fall by double digits even as population has held flat.

This jibes with a trend I wrote about in April: The miles of road lanes classified as urban is increasing while the miles of road lanes classified as rural is decreasing. But part of that shift, as Tony Dutzik, a senior policy analyst at the Frontier Group, pointed out to me then, can be explained by the ongoing classification battles that occur on the exurban fringes of growing cities, where rural roads become urban as cities expand. When a busy “rural” interstate in an Austin, Texas, exurb gets reclassified, it may shift more drivers from the “rural” to “urban” category than it does residents. Dutzik has previously shown that rural VMT decline can in large part be attributed to these boundary changes. (To make matters more complicated, the criteria vary from state to state.)

And yet: The divergence is a little too large to boil down to terminology. Sivak and Schoettle put forth four questions for future research: What characteristics of new urban arrivals might influence their driving habits? How have urban and rural economies diverged? Who drives in which places and why? And how has the internet changed driving needs, particularly in rural areas?

We know that urban growth—especially over the past few years—has been concentrated in sprawling Sun Belt metropolises, so it would make sense for driving to outpace urban population growth. Other culprits to look out for: the metropolitan character of the ongoing economic recovery (urban driving is also more likely to involve commuting), declining transit use, the (almost exclusively urban) rise of ride-hail companies, and the big mystery of how e-commerce affects driving (warehouses where consumer goods are stored, boxed, and shipped are increasingly urban).

What’s going on here? Something to ponder on your next long drive.