The U.S. Conference of Mayors is meeting this week in Miami Beach, a perfect locale for a group that, following President Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement, sees itself as the heir to America’s global leadership on climate change.

And then some: U.S. cities (and states) have also recently supplanted the federal government in negotiating with Canada. They have crafted their own immigration policies at odds with federal wishes. They are increasingly responsible for the provision of the safety net, especially as it relates to housing, as Washington and some statehouses have disclaimed responsibility for anti-poverty programs.

The enthusiasm of mayors for that role—as D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser led the chant at January’s Women’s March, “Leave us alone!”—is matched only by their unsuitability for it. Constitutional power limits and meddling legislatures in both red and blue states have curtailed municipal initiatives from the minimum wage to plastic bag bans. Any effort to effect a greater redistribution of wealth is severely hamstrung by suburban separatism. We may have new stereotypes about urbanites, and need new ones about suburbanites, but one thing remains true: Most American metropolitan areas are still doughnuts, poverty surrounded by wealth.

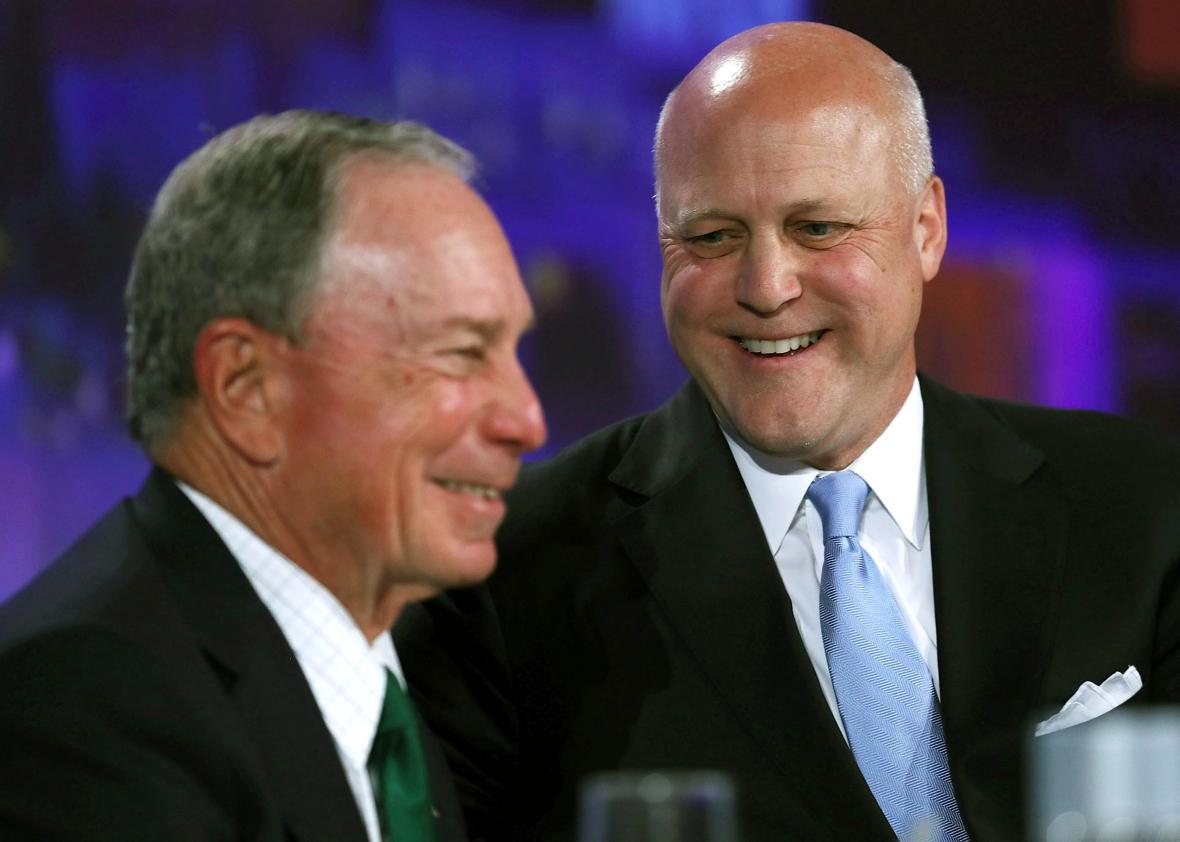

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg is here to help, he told the conference on Monday, with a new grant-making program called the American Cities Initiative. Over the next three years, Bloomberg Philanthropies will distribute $200 million to U.S. cities, beginning with a “Mayor’s Challenge” to grant $5 million to an urban project on any issue and millions more to runners-up.

The return of Bloomberg’s urbanist philanthropy, which has more recently focused on Latin America and Europe, to the American city is in response to two things, the billionaire told the New York Times. First, the recognition that cities now “replace Washington and, in some cases, state governments, to provide services.” And second, the more abstract concept that innovative urban governance is a way of restoring America’s image and influence in spite of Trump’s anti-urban agenda.

First: This is a very small amount of money for Bloomberg to dangle, especially for the big-city mayors who conduct foreign state visits and so on. The $100,000 grants dedicated to runner-up proposals in the new Mayor’s Challenge, which reprises a Bloomberg project from 2013, wouldn’t buy a public toilet. The grand prize is small potatoes relative to billion-dollar big-city budgets, and the entire dedication of $200 million is pocket change against the billions the Trump budget cuts from the transit grants, housing voucher programs, and other federal outlays on which cities depend.

Still, small grants give mayors the political capital to try new things, or go out on a limb with endeavors that might not seem like an obvious use of public money. The development of 911, for example, was spurred largely by small local grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Urban resilience efforts in the U.S. (to say nothing of city-focused journalism, including much of my own work at, say, Next City or the Guardian) have been fostered by the Rockefeller Foundation. The last time Bloomberg Philanthropies tried its challenge here, in 2013, big cities like Houston and Chicago won grants—and plenty more applied. These little gifts spur matching investments from cities and states, functioning as affirmations that something is a good idea and worthy of investment.

Since then, Bloomberg has turned his focus in the U.S. toward politics, via the quietly effective Everytown for Gun Safety project, started in the spring of 2014, and donations to candidates who support gun control or others that Bloomberg likes. In 2016, he threw $65 million into races and referenda, especially those supporting charter schools and soda taxes.

But maybe Bloomberg, a Clinton supporter who spoke at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, has come to the conclusion that money in politics is a little less effective than money with no politics. Why bother spending money on getting a candidate elected who supports your project when you can just pay for it yourself? This is a philosophy that is, on a superficial level, perfectly tailored for American mayors, whose political aims have coalesced so closely that one administration is almost indistinguishable from the next. The question is less who to elect but which of an array of competing but favored projects to pay for; Bloomberg has an answer.

Listen to the technocratic veneer that Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans and the current head of the USCM, applied to mayoral control in the New York Times: “We’re moving to a different model in this country, and it’s really going to be nonideological,” he told the paper. “It’s going to be problem-solving driven.” Technocracy is its own ideology, of course. But what Landrieu really means is that Bloomberg is going to focus on the easy stuff in cities: free money for good projects, the type that we would all fund if we could.

The more daunting, underlying problems—like regressive tax regimes, no annexation power, and political independence—will have to wait for some other benevolent billionaire.