One of the expressed intentions of Republicans’ efforts to repeal and replace Obamacare is to undo some of the age-related distribution inherent in the system. Today, healthy young people pay more so that older, less-healthy people don’t have to pay quite as much.

The Republican plan unveiled in the Senate on Thursday sharply scales back the distributional nature of the system—on an income basis, and on an age basis. The tax credits that help people afford policies on the exchanges will be sharply scaled back. So let’s say you and your spouse are 60, your kids are grown, and you’re insured on the individual market. Poverty level for a family of two is $20,420. If you make $80,000 a year between you, you’ll have to pay as much as 16 percent of your income for a high-deductible plan under the Senate’s Better Care Act as its currently written. (CNN found that, if the House plan passed last month were to become law, a 64-year-old earning $24,600 in 2026 would pay a premium of about $14,600—about 60 percent of total income.)

Asking older people to pay so much for health care is particularly devastating given the ongoing structural changes in our economy. Most Americans don’t make that much money. The median household income in the U.S. is about $55,000. But the median household income for those in the 55–64 cohort is markedly below the median for those in the 45–54 and 35–44 cohorts. Most Americans don’t have much savings. The median retirement savings for people between the ages of 50 and 55 in 2013 was $8,000.

Now, the best way to avoid paying a large chunk of your income and savings for insurance for a few years until Medicare kicks in at 65 is to keep a payroll job with health insurance. But increasingly, American employers don’t want to keep people in their 50s on their payrolls. The closer Americans get to Medicare eligibility, they more likely they are to be pushed out of their jobs—and out of the workforce entirely. The data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells the tale. In 2014, 79.6 percent of Americans between the ages of 45 and 54 were in the workforce. But of those between the ages of 55 and 59, 71.4 percent were in the workforce, while 67 percent of those aged 60–61 were and just 53 percent of those between 62 and 64 were.

In virtually every industry, at virtually every level of the income ladder, employees are explicitly seeking to move people off the payroll as they age into their 50s. Which means more of those Americans must buy insurance on the market the Republicans are currently trying to remake.

After the financial crisis, the big autoworkers worked out two-tier wage systems with unions which protected existing wages and benefits for older workers while allowing them to add new people to the payroll at lower rates and with less extravagant promises. So, of course, these large employers have lots of incentives to hasten the retirement of older workers.

Earlier this year, Fidelity Investments offered voluntary buyout packages to employees over the age of 55. In April, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston offered buyouts to employees over the age of 60. Last year the Museum of Modern Art in New York offered buyouts to, you guessed it, employees over the age of 55. In education, some states are trying to get rid of tenure, and Wisconsin has already taken steps in that direction.

You see it at the high end, too. Many professional services companies, like consulting and accounting firms, require partners to retire at the age of 60. Law firms routinely push older partners to go off counsel. At Goldman Sachs, it’s hard to find people working in senior positions past their mid-50s (unless they’re in the C-suite).

As for the media, I defy you to go into a television newsroom, digital media company, or newspaper and find more than a handful of people over the age of 50, let alone 60.

Given the relentless global competition and pressure continually to boost profits, it is likely that this dynamic will intensify in coming years. Which should push reasonable policymakers to make it easier for older people to afford health insurance on their own, either by maintaining existing premium support, or by, say, opening up Medicare to people over the age of 50. But of course, the Republican plans are going in precisely in the opposite direction.

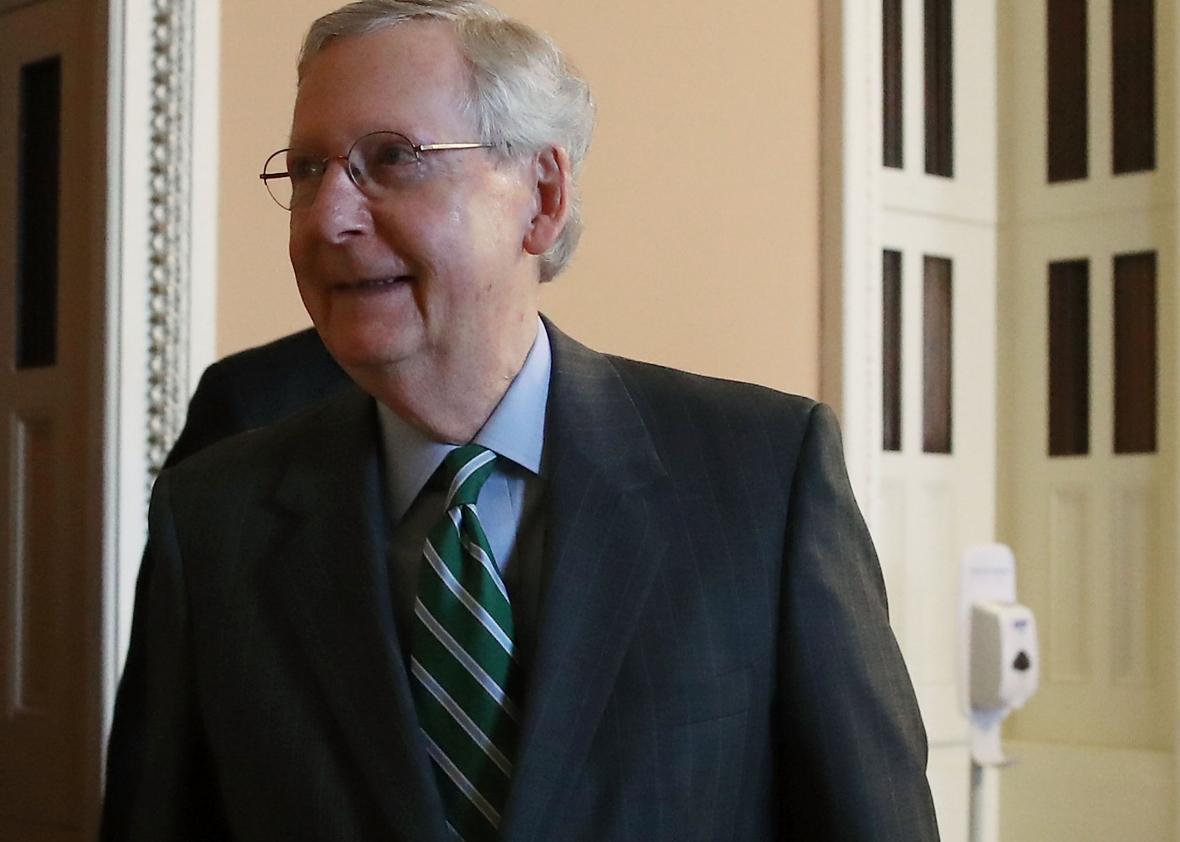

There is one area where employees who enjoy generous payroll benefits, including health insurance, can age in place. The average age in the 115th Congress is 58.